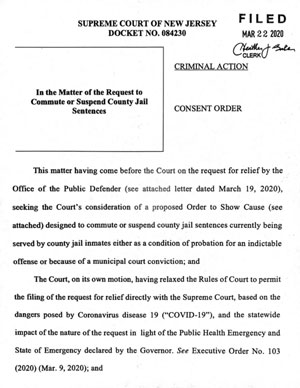

An order was signed late Sunday authorizing the release of offenders serving certain types of sentences in county jails. Credit: Ángel Franco/The New York Times.

No other state is thought to have taken such sweeping action to reduce its jail population in response to the pandemic.

New Jersey will release as many as 1,000 people from its jails in what is believed to be the nation’s broadest effort to address the risks of the highly contagious coronavirus spreading among the incarcerated.

New Jersey’s chief justice, Stuart Rabner, signed an order late Sunday authorizing the release of inmates serving certain types of sentences in county jails as the number of coronavirus cases in detention centers nationwide continues to mount.

The order applies to inmates jailed for probation violations as well as to those convicted in municipal courts or sentenced for low-level crimes in Superior Court. The release of inmates will begin Tuesday morning.

No other state is thought to have taken such sweeping action to reduce its jail population in response to the coronavirus, but other cities, including New York, Cleveland and Tulsa, Okla., have moved to release sick or vulnerable detainees.

All released inmates are encouraged to remain quarantined for 14 days.

In New York, where the number of confirmed coronavirus cases among detainees and workers at its main jail jumped to more than three dozen over the weekend, nearly two dozen people have been released.

President Trump said on Sunday that he was considering issuing an executive order to free older, nonviolent offenders from federal prisons.

In New Jersey, slightly more than 1,000 people are expected to be eligible for release, according to Alexander Shalom, a lawyer with the American Civil Liberties Union of New Jersey.

“We’re the only state in America doing this,” Gov. Philip D. Murphy said Monday during a briefing on the state’s coronavirus cases.

Prosecutors who are concerned that individuals slated for release might pose a safety risk must file objections by Monday night.

To date, there have been three reported cases of coronavirus among detainees or correction officers within New Jersey’s jails, which are run by county governments.

There have been no cases reported in its state-run prisons, where people generally serve sentences longer than a year, health officials said on Monday. Visits were suspended at all state prisons and halfway houses more than a week ago.

New Jersey’s order, signed by the state’s attorney general, Gurbir Grewal, grows out of several emergency weekend hearings in response to a motion by the state’s public defender, Joseph E. Krakora.

Mr. Grewal, a former county prosecutor, called the coronavirus “the most significant public health emergency in our state’s history.”

“I take no pleasure in temporarily suspending county jail sentences,” Mr. Grewal said.

“But when this pandemic ends, I need to be able to look my daughters in the eyes and say that I did everything I could to protect the lives of New Jersey’s residents, including those currently incarcerated.”

New Jersey’s court order comes as law enforcement officials in New York City are struggling to contain dozens of cases of the virus on Rikers Island, the nation’s second largest jail system with 5,300 inmates.

On Saturday, the number of confirmed coronavirus cases at Rikers had jumped from eight to 38 — 21 detainees, 12 jail employees and five correctional health workers, according to the Board of Correction, a city watchdog agency.

Amol Sinha, executive director of the A.C.L.U. of New Jersey, called the statewide order a “landmark agreement.”

“Unprecedented times call for rethinking the normal way of doing things,” Mr. Sinha said. “And in this case, it means releasing people who pose little risk to their communities for the sake of public health and the dignity of people who are incarcerated.”

NJ County Jail Consent Order: New Jersey’s chief justice, Stuart Rabner, signed an order to release some inmates from the state’s county jails. 14pages, 0.99M.

On Sunday, an inmate in an Essex County detention center in Newark tested positive for the coronavirus after showing symptoms. The inmate has been isolated from the general jail population and is responding well to treatment, Essex County officials said.

Correction officers in Morris County and Bergen County, the region hardest hit by the outbreak in the state with 609 confirmed cases, have tested positive for the coronavirus, officials have said.

As of Monday morning, 2,844 New Jersey residents have tested positive for coronavirus and at least 27 people have died. Nationwide, at least 33,018 people have tested positive, according to a New York Times database, and at least 428 patients with the virus have died.

A Manhattan judge assigned to work on the crisis at Rikers Island cleared 87 inmates for release but only 23 had actually been freed by Sunday night, Mayor Bill de Blasio said.

Those numbers were quickly criticized.

“What Mayor de Blasio is doing is not enough,” Eileen Maher and Jovada Senhouse, leaders of VOCAL-NY, a nonprofit, said in a statement. “He should be ensuring the release of the greatest number of people, as soon as possible.”

They added that New York City “must immediately stop sending any new people to the jails.”

New Jersey’s court order, which allows for temporary release and does not automatically commute sentences, applies only to people sent to jail after a conviction.

Lawyers for detainees who are in jail as they await trial — either because they have been deemed a flight or a safety risk — may argue for release on a case-by-case basis if their clients fall into categories considered high risk for coronavirus.

Mr. Grewal also issued guidance last Monday to law enforcement officers that was aimed at reducing the number of people booked into jails in the first place.

Absent an imminent threat to public safety, officers have been instructed to delay arrest or to issue summonses, not arrest warrants. This enables people charged with crimes to bypass jail altogether as they await court hearings.

Most in-person court hearings in New Jersey have been suspended, and no new trials have begun since the onset of the health emergency.

“It’s a common-sense approach that we have to take right now,” Mr. Grewal said.

This article was originally published by the New York Times.

Alan Feuer and Jan Ransom contributed reporting.