Nobody would mistake Cory Booker for a radical. Photo: Ethan Miller, Getty Images

Cory Booker’s Big New Policy Idea Isn’t Reparations, but It’s the Closest a Presidential Candidate Is Going to Get.

Sen. Cory Booker did not come out and propose reparations for black Americans this week. But the policy idea he rolled out on Monday might be the closest thing that we can expect to see from a serious presidential contender going into 2020.

The senator from New Jersey, who is gearing up for a White House run, plans to introduce legislation soon that would create a “baby bond” program—a concept left-wing thinkers have talked about for years as a tool that could reduce America’s yawning racial wealth gap.

Under the bill, every child born in the United States would receive a federal “opportunity account” containing $1,000, which they could not touch until they turned 18. The money would be managed by the Treasury, with the aim of earning a small annual return. But depending on a family’s income, children would receive up to an additional $2,000 each year from the government, with poorer kids getting relatively higher payments.

Booker’s office estimates that a child born into poverty could end up with approximately $46,000 to her name by the time she became an adult. She could only use the money for certain “wealth-building” purposes, such as buying a home, paying for college tuition, or retirement savings.

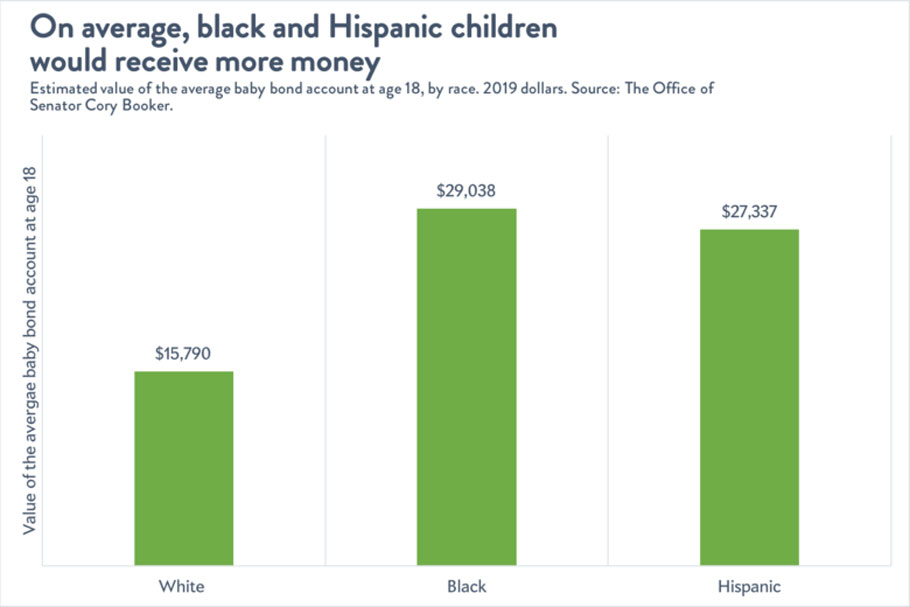

As you may have noticed, race does not factor directly into any of this. But because black and Hispanic families tend to have lower incomes than whites, their kids would receive significantly more money on average. According to a fact sheet produced by Booker’s office, the average black child could expect to have an account worth $29,038 by the time they were ready to graduate high school. White children, on average, would receive just more than half of that.

Booker’s baby bond program would be a significant step toward addressing the wealth divide between blacks and whites, which—perhaps more than any other fact of U.S. economic life—encapsulates the country’s long history of systemic discrimination against black Americans. Depending on whether you count the value of cars in the calculation, the median white household is worth either about 10 times or 41 times more than the median black household. According to New York University economist Edward Wolff, the median black household had just $3,400 of net wealth in 2016, compared with $140,500 for the median white household. (That’s the calculation that doesn’t count the family Ford, because Wolff discounts cars as depreciating assets most families can’t sell.)

Booker’s baby bond program would be a significant step toward addressing the wealth divide between blacks and whites, which—perhaps more than any other fact of U.S. economic life—encapsulates the country’s long history of systemic discrimination against black Americans. Depending on whether you count the value of cars in the calculation, the median white household is worth either about 10 times or 41 times more than the median black household. According to New York University economist Edward Wolff, the median black household had just $3,400 of net wealth in 2016, compared with $140,500 for the median white household. (That’s the calculation that doesn’t count the family Ford, because Wolff discounts cars as depreciating assets most families can’t sell.)

The fact that most black families lack any meaningful amount of wealth may also explain why their children have so much trouble moving up the economic ladder. Research by the Urban Institute has shown that even when you account for factors like parental education and income, children born into higher–net worth families are more likely to graduate college, for instance. Having financial resources matters.

The reasons underpinning the racial wealth gap are complicated—but research has shown it can’t be explained away by factors like education or family structure or frugality. As Ta-Nehisi Coates memorably wrote in his case for reparations, a large part of the problem was that black Americans were systemically prevented from buying homes and accumulating wealth by racist government policies like redlining. White Americans during and after the New Deal, meanwhile, had access to government handouts in the form of Federal Housing Administration loans that black Americans did not. Today, blacks are far less likely to receive large gifts or inheritances. On average, black Americans just don’t have much accumulated wealth to pass between generations.

Baby bonds, again, are not the same thing as reparations. The latter would be meant to be part of a process of truth and reconciliation, where the U.S. government acknowledges and apologizes for the wrongs done specifically to the black community, then makes financial restitution. Baby bonds are race-neutral and don’t involve any recognition of historic wrongs. But given how fraught racial politics are in this country, this policy might be one of the best facially race-neutral alternatives to address the wealth gap, as Darrick Hamilton, an economist at the New School who has been a key proponent of using baby bonds to address the black-white wealth gap, explained to me.

“The most salient outcome of those years of oppression directed at black people is probably exemplified in the racial wealth gap,” Hamilton, who told me he worked with Booker’s team on their proposal, said. “The most parsimonious way to address racial wealth inequality is a system of reparations. But if we’re not at the political moment for reparations, then baby bonds are a very good mechanism.”

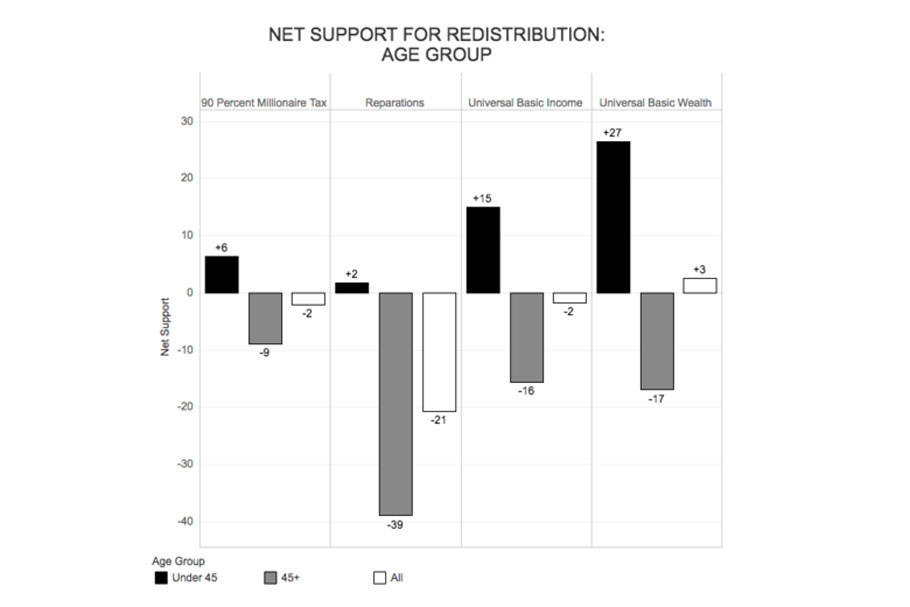

Would baby bonds really win political support from people who would oppose reparations? Polling by Data for Progress suggests they might.* The group finds that reparations are deeply unpopular overall and only enjoy 2 percent net approval among Americans under 45. Universal basic wealth—a version of baby bonds—is slightly more popular than not overall and enjoys 27 percent net approval among those under 45. In other words, white millennials and Gen Xers seem open to the idea—which isn’t entirely surprising, since baby bonds would be a way to address the wider wealth gap between America’s haves and have-nots. The program is not exclusively about racial justice, and so it appears to be more palatable to whites.

It’s possible that baby bonds would become less popular as they became a subject of debate outside wonky left-wing circles, especially if conservatives decide they are, simply, a soft version of reparations. There are also many reasons progressives might question Booker’s proposal. Some might prefer a program that gives money to families upfront when they’re raising children, such as a child allowance or the tax credits California Sen. Kamala Harris, another likely presidential contender, proposed recently.

It’s possible that baby bonds would become less popular as they became a subject of debate outside wonky left-wing circles, especially if conservatives decide they are, simply, a soft version of reparations. There are also many reasons progressives might question Booker’s proposal. Some might prefer a program that gives money to families upfront when they’re raising children, such as a child allowance or the tax credits California Sen. Kamala Harris, another likely presidential contender, proposed recently.

But if you think that the United States owes the black community financial justice for the wrongs that have been inflicted on it over time, baby bonds would be one way to come close to delivering it. It’ll be interesting to see if Booker can sell it on the campaign trail.