“William Strickland embraced the challenge of the writing of Malcolm’s life and he did so in spite of the numerous scheduling constraints placed upon a project whose release must coincide with a broadcast date. We owe him a debt of thanks for his patience, persistence, and willingness to cooperate. Bill’s perspectives helped us all on the film and book teams to understand better what it was we were trying to accomplish,” wrote Henry Hampton, executive producer of “Eyes on the Prize” and “Malcolm X: Make it Plain.”

What Hampton had to say about Dr. William (Bill) Strickland provides a compelling aperture to a life dedicated to Black scholarship and its importance to American history. Word of his passing has been announced on social media platforms, but we still await the specifics of his death. Meanwhile, the specifics of his life are well-known and he is held in high esteem in academic and activist circles.

A native of Boston, Strickland was a graduate of Boston Latin School and Harvard University. After fulfilling his military obligations as a Marine, he became active in the Civil Rights Movement and the Black liberation struggle. He applied his leadership skills to several political and educational organizations, including serving as executive director of the Northern Student Movement and working for the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and as Northern Coordinator of the party’s Congressional Challenge.

Strickland was a founding member of the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU) in 1964 and 1969. He was also instrumental in the creation of the Institute of the Black World in Atlanta. He was widely heralded for his research skills, writing ability, and general commitment to accuracy and thoroughness in scholarship. He used these proclivities effectively as a faculty member in the Afro-American Studies department at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst. A tireless administrator and teacher, his expertise on the life and legacy of W.E.B. Du Bois was acclaimed, and for many years, he was director of Du Bois’s papers, a position he held until his retirement in 2013.

The vast collection of papers are indicative of Strickland’s commitments during his time at UMass and elsewhere. Included in the collection is documentation of the time he spent working with the Rev. Jesse Jackson during Jackson’s presidential campaign, as well as his efforts in commemorating the life of baseball groundbreaker Jackie Robinson in 1996–97. This endeavor was highlighted on April 15 of this year, as major league baseball saluted Robinson’s memory and achievements.

A good example of Strickland’s scholarship and interests was published in the “Black World” in 1975, where his extended essay about Black intellectuals and the social scene aroused considerable attention. “Black America does not exist in a vacuum,” he wrote. “Analyzing the condition of Black people in America, therefore, cannot be separated from the task of analyzing America itself. And the American condition, some 10 years before George Orwell’s prophetic 1984, is one of brooding apocalypse.

“Indeed, the smell of apocalypse rises, like a stench, from every corner of the land. The cities teeter on the edge of bankruptcy; the hospitals maim and kill rather than heal and cure; the schools no longer even pretend to teach; and the economy feeds, like some Bela Lugosi vampire, on the ever-shrinking income of the citizenry. Politically, the so-called ‘two party system’ reveals itself to be little more than a second-rate Abbott and Costello comedy, while administrations past and present surface daily as skin-tight accomplices of the Mafia, the CIA, or both. Like Humpty Dumpty, the American social order is tumbling down. This breakdown in the American social order poses a particular challenge to Black intellectuals because it reveals, at the same time, a parallel breakdown of American intellectual life.

“Most American intellectuals having dedicated their lives and their careers to huckstering for ‘the greatest system the world has ever known,’ are totally unprepared to admit the meaning of the deep and searing faults which now bubble up in scandal after scandal from the nation’s democratic depths. So, at precisely the moment when new social answers are required, American intellectuals, because of their blood-knot commitment to already failed political, economic, and cultural systems, and their inability to conceive of structures, forms, modes of thought and action outside of those systems are unable even to pose the proper questions. They are trapped in the fabrications of yesteryear, enmeshed in a time which shall not come again. Black intellectuals, on the other hand, have a different legacy to draw upon, one which makes it impossible for most of us to join the anvil chorus of self-celebration which is the substance of the American intellectual tradition. We belong to the tradition of America’s victims, a tradition which has given us a particular angle of vision largely at odds with America, a tradition which has led to the repudiation, ridicule, exile and assassination of our prophets by a society determined to deny the validity of their vision and the truth of our history.”

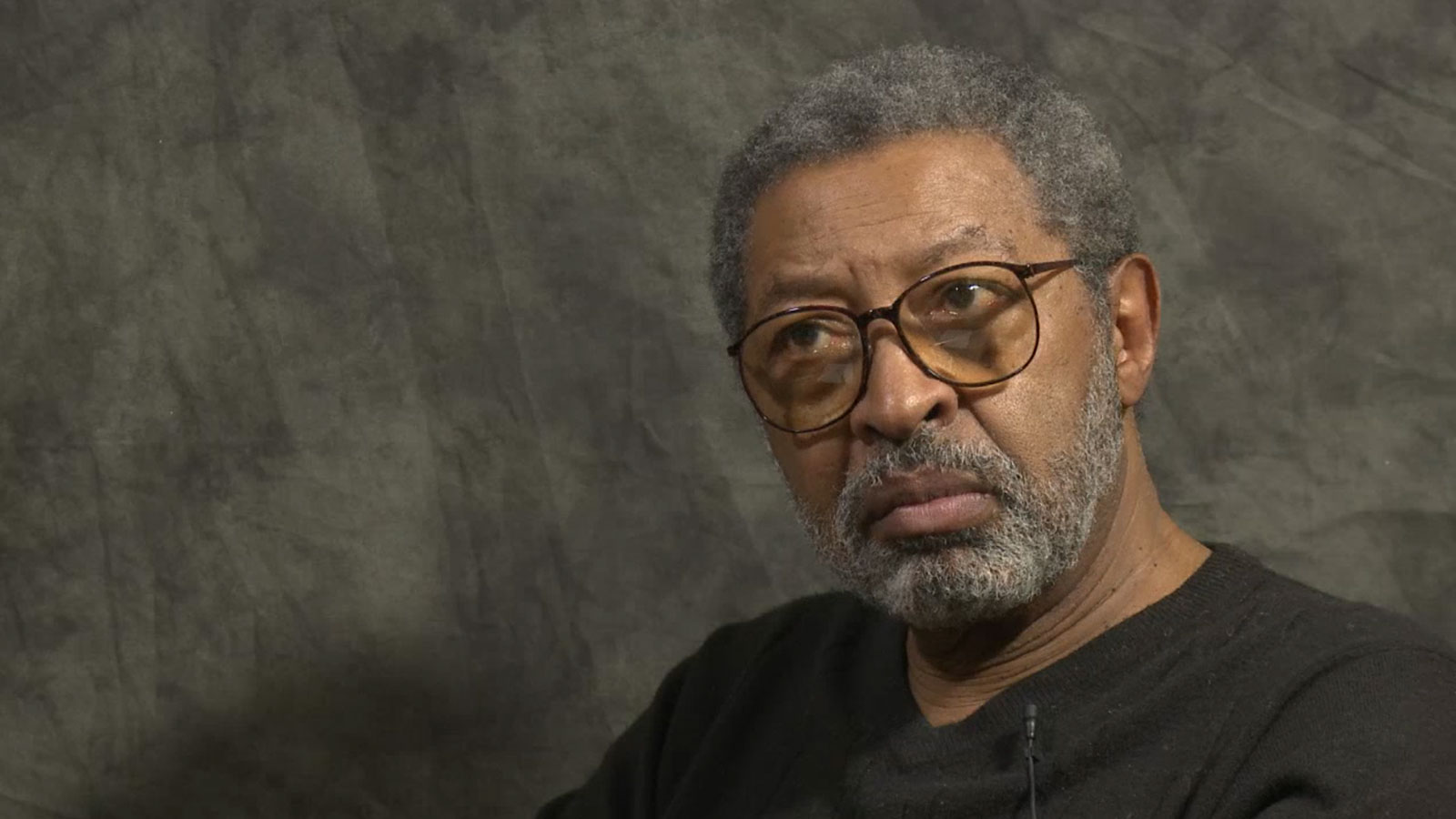

Featured image: Screenshot of Dr. William Strickland, during a Library of Congress interview (Library of Congress)