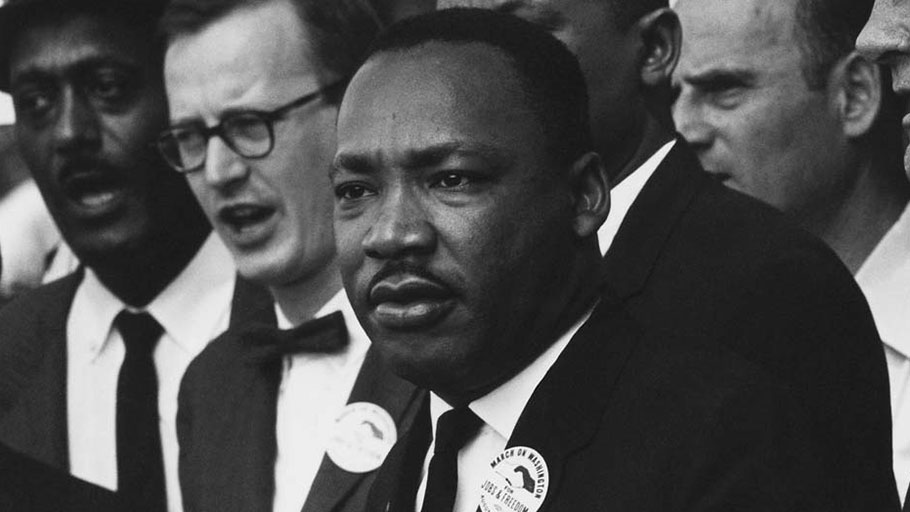

Martin Luther King, Jr., stands next to Mathew Ahmann at the 1963 Civil Rights March in Washington, D.C. (Photo Credit: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration)

King highlighted the link between systemic racism and unhealthy environmental conditions.

By Jeremy Orr, AlterNet —

As we approach the 50th anniversary of the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., I often reflect on the circumstances surrounding his death. He wasn’t murdered while boycotting the segregated bus system in Montgomery, during the March on Washington for economic justice, or while marching for voting rights in Selma.

He was slain in Memphis, Tennessee, while organizing the Sanitation Workers Strike as part of his 1968 Poor People’s Campaign—a campaign that highlighted the link between systemic racism and the unhealthy environmental conditions suffered by poor black sanitation workers.

At the time, King was engaged in an early battle for what we now call environmental justice, which the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency defines as “the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin or income, with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.”

Environmental justice is something I believe passionately in and to which I’ve dedicated much of my life.

Creating equity in climate adaptation work is also what the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People has recognized as a call to action. We see energy injustice is a crisis of unprecedented proportions—not only for black communities but for all frontline communities that are hit first and worst by the environmental impacts of non-renewable energy and corporate greed. So we created the Environmental and Climate Justice Program (ECJ), spearheaded by Jacqueline Patterson, co-founder of Women of Color United. I proudly serve as the Environmental and Climate Justice Chair for Michigan’s NAACP State Area Conference, a collective of NAACP branches in the Michigan region.

As a Detroit native, I know all too well the harms caused when elected and appointed officials at all levels of government neglect the environmental issues that impact vulnerable communities. In my community, people color and low- to moderate-income neighborhoods suffer higher rates of respiratory diseases like asthma because trash incinerators and oil refineries are permitted to pollute the air that we breathe.

Our children disproportionately struggle with dirty air quality illnesses because our Detroit leaders have dragged their feet on creating Climate Resilience Plans. Because public and private utility companies charge astronomical rates and shut off the services of the already overburdened consumers who simply cannot afford to pay, there are numerous homes without electricity in our communities. It is simply unconscionable. Utility shut-offs are so problematic that the NAACP’s ECJ Program wrote a report about it: Lights Out in the Cold: Reforming Utility Shut-Off Policies as if Human Rights Matter.

Because of illegal water shut-offs and government corruption, our people are dying. Detroit is a largely a black city. The connections to the poisoning of black communities and environmental racism cannot be denied. My fellow Michiganders just up the road in Flint can speak to that.

It’s been almost 50 years since Dr. King’s fight, yet poor communities of color continue to fight against environmental racism today. And with the current White House Administration’s lack of regard for—or sheer ignorance of—things like science and reason, our stand for environmental and climate justice has never been more important.

So what are we doing about it?

My environmental justice work with NAACP in Michigan is one of the hundreds of efforts across the country by NAACP branches to bring energy justice to their communities and on September 25, the ECJ Program at NAACP launched a campaign to recognize and uplift their branches’ hard work.

Power to the People: Fueling the Revolution for Energy Justice highlights the groundbreaking and innovative energy justice projects that over 2,200 NAACP units across the country are doing to bring clean air, clean water and clean energy into their communities. NAACP units are leading the way in creating green jobs, shutting down toxic coal plants and creating community scientists in their neighborhoods. They are drafting legislation to bring net metering into their homes, organizing for wind energy, and most importantly, creating healthier environments for black and poor communities.

Renowned environmental law professor Noah Hall once said to me, “Environmental regulation in America is as unjust as our criminal justice system. If you’re white and have resources, you’ll be fine. But if you’re a poor person of color, it’s an uphill battle.”

As a bright-eyed and bushy-tailed environmental justice lawyer at the time, it pained me to admit it, but I knew that he was right. However, I also knew that I came from a community of resilient people who, when faced with adversity, have always overcome. The struggle to secure a safe and healthy environmental and climate future for black and brown communities shall be no different.

Knowing what’s at stake, I am committed to standing with the NAACP at the forefront of this new revolution—the revolution for energy justice.

Special thanks to Katherine Taylor, NAACP’s Environmental & Climate Justice Communication’s Manager, for her editing expertise and partnership in the movement.

Jeremy Orr is a civil rights attorney and the State Chairperson of Environmental & Climate Justice for the Michigan State Conference NAACP.