From the steps of St. Charles Borromeo at 20th and Christian, in the heart of the neighborhood, you can see the new Comcast tower and the Center City skyline.

Searching for a new identity, Philadelphia’s most gentrified neighborhood looks to its African American past.

By Inga Saffron, Architecture Critic, Philly.com —

If there’s one thing that Graduate Hospital residents seem to agree on, it’s that the name of their neighborhood is generic, confusing, and altogether lame.

The institution that inspired the name no longer exists, having gone out of business more than a decade ago. What may be even more of an indignity is that most of the former hospital buildings are actually in Center City, the neighborhood immediately to the north.

The name Graduate Hospital was concocted by real estate agents in the ’70s, when it was hard to lure home buyers out of Philadelphia’s core. But the hospital’s name carried so little meaning that Wikipedia revised its entry right after the University of Pennsylvania converted the property into medical offices in 2007. The new name? Penn Medicine Rittenhouse. Yet Graduate Hospital is still how the neighborhood is known.

Some residents are hoping to change that. Last month, Kevin Brown, who chairs the community group, which (to confuse things further) is called the South of South Street Neighborhood Association, sent out a mass email arguing that it was time to give the neighborhood a new identity. To get the discussion rolling, he suggested “Marian Anderson Village,” in honor of the celebrated opera singer and African American civil rights figure who grew up on Martin Street. But Brown believes that “any name that is not Graduate Hospital is a good name.”

Garden blocks like this one on St. Albans Street are a distinguishing feature of the Graduate Hospital neighborhood. Photo by Inga Saffron

Renaming neighborhoods is hardly a new phenomenon in Philadelphia. Over the last two decades, as real estate has evolved into the city’s favorite sport, any number of previously nameless collections of rowhouse blocks have sought to niche-brand themselves. There was a time when people might have considered Fairmount, Francisville, and Brewerytown all part of the great expanse of North Philadelphia, but no more.

Still, the rebranding of Graduate Hospital would be different from other niche-naming in one key respect: Most changes are used to scrub neighborhoods of their pasts and assert the aspirations of their new residents. Instead of inventing a fresh neighborhood identity, Brown wants to connect today’s residents with a rapidly vanishing one.

Kevin Brown, the chair of SOSNA, walks by Julian Abele Park at 22nd and Montrose Streets. It was named after the noted African American architect who lived in the neighborhood. Photo by Inga Saffron

Graduate Hospital holds the distinction of being the most gentrified neighborhood in Philadelphia, according to a 2016 Pew study. As recently as 1990, African Americans made up 90 percent of the population in the slice of city geography sandwiched between South Street and Washington Avenue, and bounded by Broad Street and the Schuylkill. But today, the African American presence is down to around 35 percent, and you can hardly touch a house for under $500,000.

The facade of the historic Royal Theater on South Street is all that survives today. The rest of theater was demolished and the remains will be incorporated into a residential project by developer Ori Feibush. Photo by Inga Saffron

The area has a rich and varied history. It was home to some of Philadelphia’s most accomplished black professionals, including the architect Julian Abele, who helped design the Free Library and Philadelphia Museum of Art. You can still see their legacy in institutions like the Christian Street YMCA, the Royal Theater, the Hotel Brotherhood USA, and numerous black churches. It’s also the place where the annual Odunde festival is held, drawing back hundreds of former residents.

“In the next 10 or 12 years, the neighborhood will be almost completely white,” predicts Rob Watson, 47, an African American who is the third generation from his family to live in the neighborhood.

Once he could count dozens of cousins living within a few-block radius, but virtually all his relatives have left, mostly for opportunities beyond Philadelphia. His daughter attends the increasingly desirable Chester Arthur elementary school and has plenty of friends, “but fewer and fewer of them are black,” Watson says. Even though he owns a home on a picture-perfect block, he often thinks about cashing out to buy a bigger house elsewhere in the city. To him, the conversation about renaming the neighborhood feels like a useless exercise because it can’t restore the web of relationships he once enjoyed.

Graduate Hospital residents line up for a SOSNA meeting to discuss the plan for the recently demolished Chocolate Factory on Washington Avenue. Photo by Inga Saffron

Graduate Hospital’s demographic transformation happened so quickly, Brown says, that many didn’t realize it was occurring. Gentrification was preceded by massive depopulation, brought on by a failed, ’60s-era plan to run an interstate highway down South Street. The neighborhood lost half of its residents between 1960 and 1990.

Brown’s idea of naming the neighborhood after Marian Anderson has generated plenty of conversation, and not a little soul-searching. At a time when American communities are starting to remove offensive names and monuments that memorialize racist figures, Brown’s proposal would affirmatively celebrate the neighborhood’s African American heritage. “We as newcomers have an obligation to understand and honor the neighborhood’s history,” he argues.

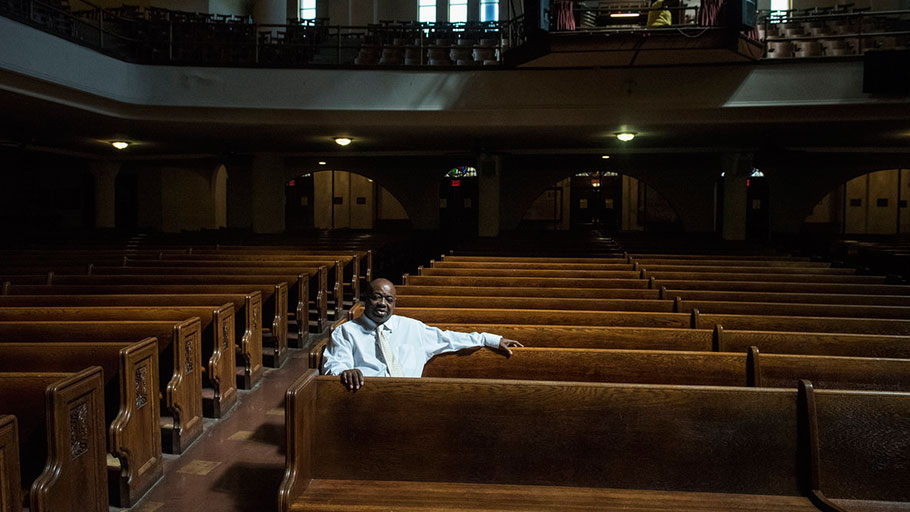

His suggestion has been met with a resounding “maybe” by both black and white residents. The Rev. Robert Johnson, who grew up in the neighborhood and is now the pastor of Tindley Temple on Broad Street — where the song “We Shall Overcome” gained its final form — agrees that naming the neighborhood for Anderson would be a nice tribute, but only if it is part of an inclusive community dialogue.

“The name means nothing if you’re not going to address the needs of the people,” he says. “Right now, there is no conversation about keeping people in their homes.” That hit home when a developer announced plans to build $2 million townhomes on the vacant lot next to his church.

Rev. Robert Johnson, who grew up in the neighborhood, now presides over Tindley Temple United Methodist, an historic black church that is down to 150 regular congregants. Photo by Inga Saffron

Actually, people like Johnson and Watson never called the neighborhood Graduate Hospital. “To me, everything south of South is South Philly,” says Watson.

The blandness of the Graduate Hospital name may be a reflection of its geography. The equivalent band of territory on the east side of Broad has three neighborhood designations.

Devil’ss Pocket Food and Spirits uses one of the popular niche names. Photo by Inga Saffron

The name Graduate Hospital was always something of a placeholder. The Planning Commission calls the area “Southwest Center City,” a designation that horrifies some residents who see themselves as distinct from the downtown crowd. The Pew report oddly refers to the neighborhood as “Schuylkill.” That’s an old name that was reserved for an area along the river. There’s also a largely Irish enclave nearby known as Devil’s Pocket. A few years ago, writer Brad Maule jokingly nicknamed the neighborhood “G-Ho.” To his surprise, the name continues to be used.

From the Pierce School at Cambria Street, you can see the Veolia Steam plant on the Schuylkill waterfront. Photo by Inga Saffron

The biggest challenge with finding a name for the neighborhood is that it has few defining geographical features or architectural markers that could inspire a name. It is simply a bedroom city, a vast expanse that is dense with rowhouses and churches.

The monuments that do exist are all struggling for their survival. Over the last few years, the neighborhood has lost two major industrial icons, the Civil War-era Chocolate Factory on Washington Avenue and the art deco Marine Corps Depot on Schuylkill Avenue, where the Children’s Hospital complex now stands, as well as several churches. As the black population continues to decline, it’s almost certain that more sanctuaries will become vulnerable.

Maybe the real issue isn’t Graduate Hospital’s name, but how to protect its historic touchstones, so that the culture that inspired them remains visible to future residents of whatever this neighborhood is called.

Rev. Robert Johnson stands on the Broad Street next to his church where a New York developer is planning to build $2 million townhouses. Photo by Inga Saffron