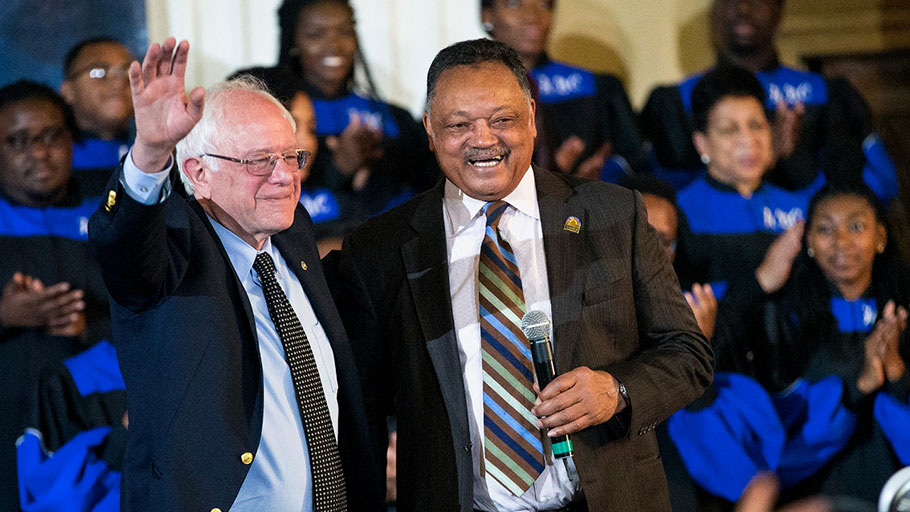

Democratic presidential candidate Sen. Bernie Sanders waves to guests after being interviewed by Rev. Jesse Jackson at Operation Rainbow Push in Chicago on March 12, 2016. Photo: Scott Olson/Getty Images

Sanders was a key supporter of Jackson’s 1988 presidential campaign, which came stunningly close to an upset.

Michigan holds a special place in the memory of Jesse Jackson and the supporters of his insurgent 1988 presidential campaign. It was Jackson’s Nevada, the moment that the party establishment realized this campaign it had long written off might just seize the nomination.

At a rally in Michigan on Sunday, Jackson will endorse Sanders ahead of a do-or-die primary for the Vermont senator.

Jackson’s Michigan contest in 1988 fell on March 27. After more than three dozen primaries and caucuses, a crowded presidential field had been winnowed down to three serious contenders: Michael Dukakis, the Massachusetts governor and presumed frontrunner; Missouri Rep. Dick Gephardt; and Jackson, a former close aide to Martin Luther King Jr. and the public bearer of the civil rights movement’s torch.

Joe Biden, then a senator from Delaware, had dropped out of the race following a plagiarism scandal and dismal polling numbers.

Given Gephardt’s hard-hat, working-class brand, he badly needed a win in Michigan. He threw everything he had left into the state. Dukakis, too, wanted Michigan — to show that his appeal extended beyond the liberal confines of Harvard Square, and that he could win back those Reagan Democrats whose defection had cost Jimmy Carter reelection.

Jackson spent that election day touring Detroit, hitting black churches and five different housing projects. The New York Times’ legendary political reporter, R.W. Apple, was on hand for the last minute push. Jackson, Apple observed in his election night dispatch, “had drawn surprisingly large crowds of both blacks and whites in the last few days,” adding that despite the black establishment’s support of Michael Dukakis — Detroit Mayor Coleman Young was backing Dukakis — Jackson won some Detroit neighborhoods by 15 or 20 to one. “But the surprise was the Chicago clergyman’s powerful showing in predominantly white cities like Lansing, Flint, Kalamazoo and Battle Creek, several of which he carried.”

Indeed, Jackson did more than get out the black vote. Progressive white voters in the state also rallied hard to his cause. (Dean Baker, now a prominent progressive economist, was district director for Jackson in Ann Arbor.)

The energy of the moment comes through in the Times dispatch. “So dramatically did [Jackson] seize the public imagination that he was able to counter successfully the notion that Mr. Dukakis was the Democrat with the best chance of nomination,” the Times wrote.

Jackson, after 37 primaries and caucuses, was now effectively tied with Dukakis in the delegate count — a stunning moment in American politics that has gone down the memory hole.

The victory generated two polar opposite responses in Washington, D.C., and Burlington, Vermont, both of which would have profound implications for the future of the party.

In Burlington, the city’s independent mayor, an outspoken supporter of Jackson, had to decide if he would engage directly with the Democratic Party in order to help Jackson win. After the Michigan victory, Bernie Sanders went all in, calling a local press conference and announcing that he would be participating in the April Democratic caucus to back Jackson. “I am the only non-Democrat, non-Republican, independent progressive mayor in the United States of America. OK, it is awkward, I freely admit, it is awkward for me to walk into a Democratic Party caucus, believe me, it is awkward. I am not a Democrat. Period,” he said.

But he said the stakes were too high, and the opportunity too great, to stand aside on principle. Jackson, he argued, could remake the Democratic Party in an image of social justice. “So while in fact, he may end up losing some conservative white votes, some racist white votes, I think there is a real chance that he could do what [Walter] Mondale couldn’t do in a million years. That is to bring millions and millions of poor people and working people into the political arena who in the past never participated.”

‘Pick up your sling shot, pick up your rock, declare our time has come, a new day has begun!’ — Rev. Jesse Jackson’s iconic ‘David and Goliath’ speech from 1984 is just as relevant today pic.twitter.com/uCbW2W5UFy

— NowThis (@nowthisnews) February 6, 2020

In Washington, though, the reaction was pandemonium. Just as party leaders melted down publicly after Sanders’s win in the Nevada caucuses, they did so after Jackson’s triumph in Michigan. Talk in the top echelons of the Democratic Party turned to panic, with David Espo of the Associated Press reporting that the establishment feared a general election blowout if Jackson was the nominee. Plans were being drawn up, he reported, to draft New York Gov. Mario Cuomo to challenge Jackson at the convention if Dukakis couldn’t stop the reverend.

E.J. Dionne, then reporting for the New York Times, captured the sense of dread.

White Democratic leaders who do not support Mr. Jackson admitted they were in a quandary, wondering how to confront the growing movement toward Mr. Jackson without appearing to be racist and without alienating the large core of activists, including many white liberals, that he has attracted….

Around Washington, the words used by leading white Democrats to describe their party’s situation included crisis, disarray, disaster, consternation, mess, and wacky.

“You’ve never heard a sense of panic sweep the party as it has in the last few days,” said David Garth, an adviser to Senator Albert Gore Jr. of Tennessee.

Mr. Garth predicted that ‘”the anti-Jackson constituency, when the reality of his becoming President seeps in, may be a much bigger constituency than there is out there right now.”

Jackson, the Democratic political class argued, was simply unelectable, so the party should go with a winner like Dukakis. Rep. Barney Frank’s sister, Ann Lewis, was working for the Jackson campaign, but Frank was backing his home state governor. He explained to Dionne that there were two reasons Jackson couldn’t win. “One, there is unfortunately still racism in the country. … That doesn’t mean the whole country’s prejudiced. It means that if there’s an irreducible 15 or 20 percent prejudice against a particular group, you’re giving away an awful lot,” Frank said. “Two, he’s still to the left of the country, especially on foreign policy.”

Jackson’s opponents had argued that his proximity to the nomination would paradoxically push some white Democrats away from him. It’s all fine and good to vote for the charismatic black guy with the unifying message in 1988 — indeed, it was an anti-racist badge of honor — just not if he actually might win. The party establishment pulled the fire alarm. I asked Jackson, in an interview for my recent book, “We’ve Got People,” what kind of pressure he felt after his Michigan win. “The pressure was not on me,” he said. “It was the so-called Reagan Democrats who began sewing discord and spreading lies.”

At the April Democratic caucus in Vermont, Sanders spoke on Jackson’s behalf. The interloper’s speech did not go over well with every Democrat. As he headed back to his seat, a woman in the audience slapped him across the face, he later recounted in his 1997 book, “Outsider in the House.”

“Bernie represents direction not complexion. He stood up for me in ’88, and we won Vermont — the whitest state in the country,” Jackson recently recalled to Jeremy Scahill. On the back of the progressive coalition Sanders had organized in Vermont, Jackson won the Vermont caucuses 46 to 45 percent.

Outside of Vermont, it didn’t go as well. Jackson had been polling ahead in the next state on the calendar, Wisconsin, but the party consolidation behind Dukakis, fueled by the panic, flipped the momentum, and Dukakis took the state.

Over the next month, Dukakis would win Pennsylvania, New York, Ohio, and Indiana, and while Jackson continued picking off a state here and some delegates there, the nomination contest was effectively over. As is often the case, political wisdom failed the party elite, and Dukakis was crushed by the unpopular George H.W. Bush.

Jackson’s endorsement comes in the wake of Elizabeth Warren’s departure from the race. “I will not go against Bernie, but I’ve not made a decision to endorse anybody,” Jackson said in a February episode of Intercepted. “And when we talk, I share with him observations. Same with Warren, share observations. I’m not endorsing either one at this point.”

But Jackson was clear on who he would not be supporting. “I think the idea that somehow Biden has largely inherited the black vote in South Carolina is not sound judgment,” he said. “We were saying no to Clarence Thomas; he said yes to Clarence Thomas. We were saying no to the crime bill. He said yes to the crime bill. No to the Iraq War. He said yes to the Iraq War. He’s on a different side of history. It’s his right to be there, but he might as well own up to his side of history.”

Jackson said that Biden had taken on the aura of Obama, though that misunderstood the role Biden had played on the Obama’s ticket. “Joe Biden is seen as connected to Barack. He was put on the ticket to balance the ticket not to enhance it. Barack was against the Iraq War. He was for the Iraq War. Barack was against the crime bill. He was for the crime bill. Barack was supporting Anita Hill, and Biden let Clarence Thomas on the Supreme Court as a monument to his leadership in that committee. So his proximity to Barack gives the impression he is active in civil rights is clearer than it is,” Jackson said. “Biden was Barack’s right wing. With Barack out, there’s nothing left but the right wing.”

Biden isn’t offering a vision that meets the moment, Jackson said. “His message does not address the pain of our people. I’m not sure what moderate means if people don’t have affordable health care. I’m not sure what moderate, ‘I’m a moderate’ means to us. In fact, it means very little to us,” he said.

Just as Biden isn’t moderate, Jackson argued, Sanders isn’t on the left. “What Sanders represents is not the left wing,” he said. “It’s the moral center. Health care for everybody is moral. Education even for the poor without student loan debt is the moral center. Middle East policy where you recognize Israel and Palestine is the moral center.”

This article was originally published by The Intercept.

Ryan Grim is the author of the book “We’ve Got People: From Jesse Jackson to Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the End of Big Money and the Rise of a Movement.”