By Constance Grady —

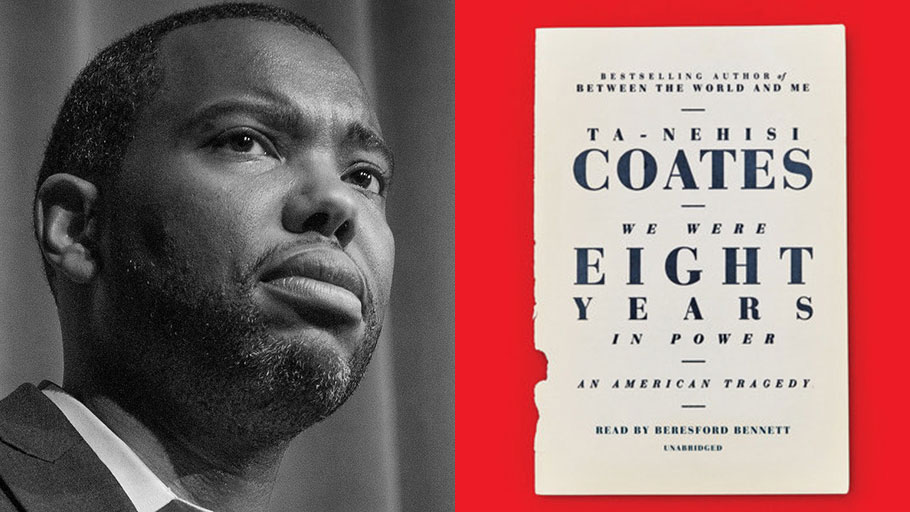

We Were Eight Years in Power, the new book by Ta-Nehisi Coates, is not precisely new. It’s a collection of eight articles Coates wrote for the Atlantic, starting in 2007 during Barack Obama’s presidential campaign, concluding this year with the start of Donald Trump’s administration, and including some of Coates’s greatest hits, including his much-lauded 2014 article “The Case for Reparations.” What’s new is that each of the eight articles is introduced by an essay in which Coates lays out its context: what was happening in America when he wrote it, and what was happening in his own development as a writer.

Ultimately, those two narrative arcs form the spine of the book. In We Were Eight Years in Power, you can see America at first embracing the policy of a black president and then reacting in a violent and paranoid racist backlash, and you can see Coates developing both the theoretical tools and the lyrical, expressive voice that makes his analysis of that backlash so captivating.

“I could hear what that voice sounded like in my head,” Coates writes of the voice he was aiming for as he profiled Michelle Obama. “It was a blues with a beat dirtier than anything I had ever heard anywhere in the world.” He didn’t, he concludes, capture such a voice in the profile, but as you read We Were Eight Years in Power, you’ll hear Coates incrementally refine and clarify his distinctive voice — steeped in poetry and hip-hop and the rhetoric of black liberation — into the formidable tool it’s become today.

For Coates, style and content are inextricably linked

Coates thinks of the aesthetics of his sentences as being inseparable from their content. His model is James Baldwin; for Coates, Baldwin’s writing is beautiful specifically because it is honest. “The beauty of Baldwin’s prose that I connected to was not ancillary to the dream-breaking but central to it,” he writes. “The beauty in his writing wasn’t just style or ornament but an unparalleled ability to see what was before him clearly and then lay that vision, with that same clarity, before the world.”

Beautiful prose, for Coates, is necessarily honest prose. Honest prose must tell the truth about America — and the truth is, he argues, that white supremacy is not incidental to America’s history or to its current wealth, but foundational to it. “America is literally unimaginable without plundered labor shackled to plundered land,” he writes, “without the organizing principle of whiteness as citizenship, without the culture crafted by the plundered, and without that culture itself being plundered.”

The drive to render this reality with honesty and clarity creates Coates’s evocative, emphatic sentences: To make the reader experience the horror of white supremacy with honesty, Coates must kill cliché.

Over the course of Eight Years, you can watch Coates develop the particular habits of diction and syntax that he falls back on in service of this quest: the repeated rendering of the black self as a black body, upon which racism works with physical force; the use of the word plunder to describe how white supremacy takes possession of black wealth and labor; the preacher-like repetition of sentence structure in a long cascading litany of American sins; the which is to say that links abstract, morally charged ideas to concrete action, illuminating both. Coates writes “about race, which is to say the force of white supremacy.” Nations are “atheists, which is to say they find their strength not in any God but in their guns.” Nas’s lyrics are “beautiful, which is to say [they are] grounded in the concrete fact of slavery.”

These writerly habits are not crutches or safety blankets; they’re carefully developed tools that serve a specific argumentative purpose. Part of the pleasure of reading Eight Years lies in watching Coates discover and refine these tools and then slowly discard them as they live out their purpose.

As the book ends, Coates is beginning to point his analytical attention in new directions

As Eight Years concludes, Coates writes, he is no longer as interested as he once was in arguing about the formation of America’s color line. He has made his investigations, seen the data, and convinced himself, but he is fairly certain that the rest of the country won’t care: “It simply broke too much of America’s sense of its own identity,” he writes. “So I felt after this last piece that I was done arguing. I was resigned. I was at peace.”

That air of resignation begins to bleed into Coates’s writing even before his last essay. He wrote “The Black Family in the Age of Mass Incarceration” in 2015, and it pulls extensively from the analytical framework he established in “The Case for Reparations” and his second book, the National Book Award–winning Between the World and Me. It is, like all of Coates’s major essays, well researched and well argued, but it lacks the urgent, evocative sentences of his other work. That may be in part because it doesn’t make major theoretical contributions to the analysis Coates had already done. “It was, in many ways, an end point for my inquiries,” Coates writes.

Part of what animates Coates’s writing seems to be the desire to learn for himself. He waxes lyrical on his hope that “I and all my wonder, my long-lost friend, have not yet run out of time,” and on his love for his now-defunct blog, where he could build up a base of knowledge and interact with experts. “The Black Family in the Age of Mass Incarceration” doesn’t seem to offer Coates any new avenues for understanding the world, and as a result, it’s a quieter, less energetic piece of writing than its fellows in this book.

The story that Coates is telling about America throughout these eight essays ends with the election of Donald Trump, which for Coates is both inevitable and horrific. “Our story is a tragedy,” he concludes, although “that belief does not depress me. It focuses me.”

But the story Coates is telling about his own development as a writer ends differently. It ends with one of America’s greatest thinkers beginning to turn to new questions and recommitting himself to helping create “a world more humane.”

“My ambition is to write both in defiance of tragedy and in blindness of its possibility,” he says, “to keep screaming into the waves — just as my ancestors did.”