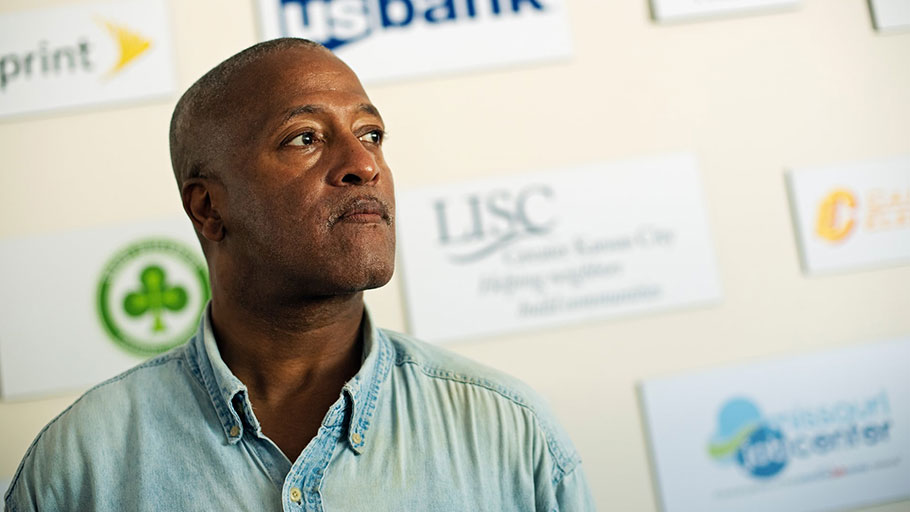

In a city nearing full employment, Carl still struggles to find work. Photograph: Jason Dailey for the Guardian

As Trump highlights declining jobless figures, Kansas City offers a window into how the recovery has passed many African Americans by.

By Caleb Gayle, The Guardian —

Kansas City is booming. Employers and investors have poured into the midwestern city since the recession. At least $1bn has gone into its sparkling new downtown, revitalized arts district and shiny new condos. So why is Sly James, its highly regarded outgoing mayor, so unhappy?

James, who steps down in July 2019, is leaving office with a sense of disappointment that despite Kansas City’s obvious accomplishments, the city’s recovery has left one large section of society behind: African Americans.

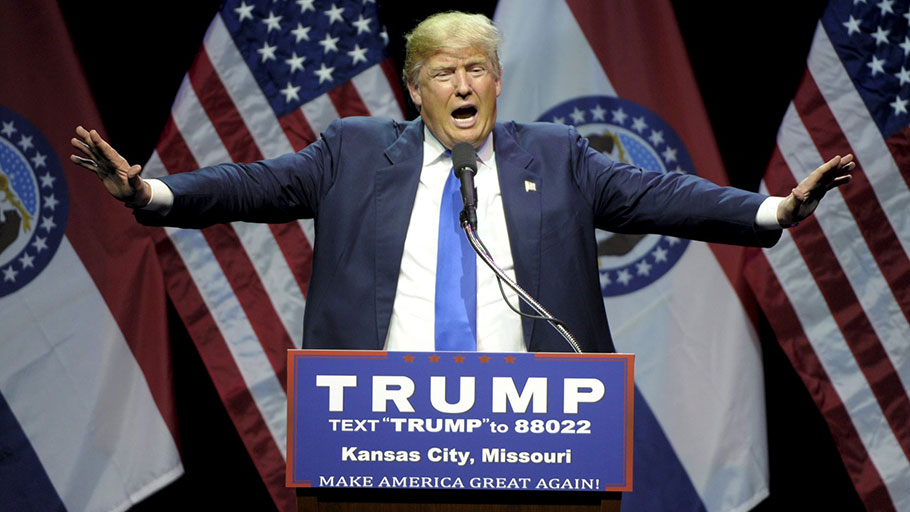

About 30% of Kansas City’s population is black. Every month, seemingly, Donald Trump uses Twitter to trumpet how well black people have done under his presidency. Nationwide African American unemployment is now 6.5%, down from a peak of 16.8% at the height of the recession.

But national numbers in a country as big as the US can be misleading. For many African Americans in the Kansas City area, the spoils of a roaring recovery have passed them by.

Stock Market up almost 40% since the Election, with 7 Trillion Dollars of U.S. value built throughout the economy. Lowest unemployment rate in many decades, with Black & Hispanic unemployment lowest in History, and Female unemployment lowest in 21 years. Highest confidence ever!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) June 11, 2018

“The impact of all things racial has left neighborhoods divided and segregated and that leads to a perpetuation of things like poverty and lack of opportunity,” says James, adding he would “have to disagree [with anyone] who says that the real African American unemployment situation is 5.9%”.

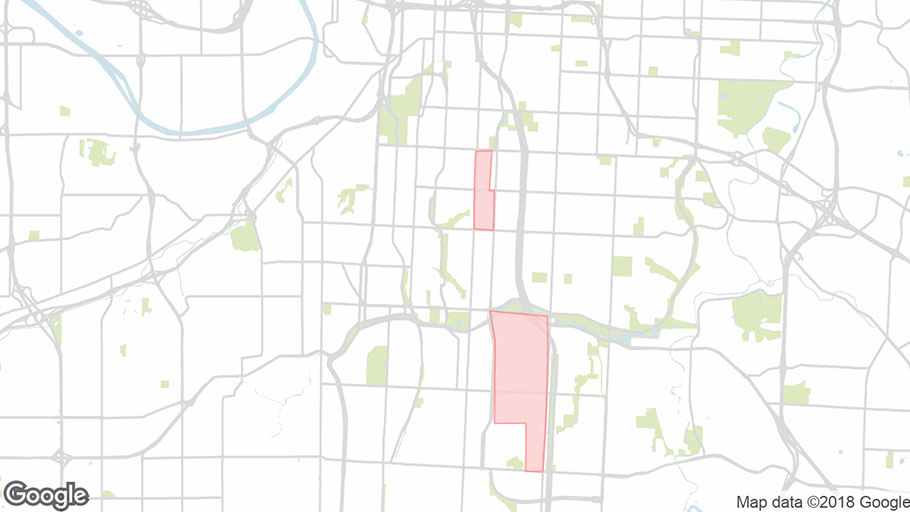

Kansas City may boast an unemployment rate of 3.6%. But take the city’s Blue Hills neighbourhood. Blue Hills is 91% African American and the unemployment rate is 17%. Neighbouring Ivanhoe is 86% African American and the unemployment rate is even higher, at 26%.

James is not alone in his assessment of his city. A loud chorus of individuals looks skeptically at the numbers Trump so proudly presents. Decreasing unemployment figures would usually signal that things are going well. But when you are one of the 14.3% of black people paid a poverty wage, compared with the 8.3% of white people who receive a poverty wage, it doesn’t feel like it.

James is not alone in his assessment of his city. A loud chorus of individuals looks skeptically at the numbers Trump so proudly presents. Decreasing unemployment figures would usually signal that things are going well. But when you are one of the 14.3% of black people paid a poverty wage, compared with the 8.3% of white people who receive a poverty wage, it doesn’t feel like it.

As with the rest of the United States’ recovery from the 2008 recession, Kansas City’s comeback still carries the scars of the structural and intentional racism of its not-so-distant past.

Carl, who did not want his last name published, is 57 years old and has big dreams: “I want to save up, put something aside for a proper burial, pay off my house, keep up with my car payments and pay that off. Typical American dream stuff,” he says. But his access to the American dream had to be deferred.

Carl has been unemployed for nearly a year, collecting social security insurance after a hip replacement following an incident on his full-time construction job.

Carl may be unemployed but he still works hard. The white blotches of his graying hair nearly match the white of his tightly starched button-down shirt and well-shined, tuxedo shoes. Most telling are the smoothed calluses on his fingertips; one of his many jobs is playing the bass guitar for his local church.

“One Sunday an announcement was made at the church about job workshops,” he says. He hustled, calling the numbers listed on the pamphlets left on the back of church tables. “After doing that program, I heard about the financial opportunity centers.”

These financial opportunity centers (FOCs) are a pillar program of the Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC), where, according to Trese Booze, who heads these FOCs in Kansas City, coaches help “overlooked talent to prepare them for quality, living-wage jobs, while becoming resilient to financial shock”.

Maurice Jones, LISC’s national CEO, says the goal was for participants to become “net cash positive”, culminating in a life plan that is “inspiring to them”. People just like Carl make their way into FOCs at a variety of points on their employment trajectory.

Donald Trump at a rally in Kansas City during the presidential race. Photograph: Dave Kaup/Reuters

For Carl, a felony conviction has made getting a job trickier than usual. He says he was pressured into a plea deal after brandishing an unregistered firearm in self-defense, in response to being threatened several times by gang members in his apartment complex.

Like many with criminal records around the country, Carl must jump the hurdles of the “collateral consequences of convictions” if he is to get a job. According to the National Inventory of Collateral Consequences of Convictions (NICCC) compiled by the Council of State Governments, Carl could face up to 185 legally sanctioned barriers in Kansas to different kinds of employment and job certifications because of his conviction. In Missouri, that number increases to 313 – and that is before any consideration of the intangible effects of perception of being a black man with a felony conviction.

According to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), “a criminal record can reduce the likelihood of a callback or job offer by nearly 50%” – nearly twice the impact suffered by white peers with a criminal record.

The declining unemployment numbers Trump touts on Twitter do not account for the nearly 2.3 million “unemployed” African Americans in prison, who make up nearly 34% of the total US prison population.

Carl’s criminal record and the hip replacement that lost him both his “side-hustle” as a home-health provider and his full-time construction gig haven’t stopped his penchant for hustling.

If you’re in Kansas City, he might be your beautician or barber. He might be your bass guitarist in a wedding or church band. And in Carl’s words: “I’ve dug ditches and I’d do it again to keep up with the payments if it wasn’t for my injury.”

Shellie, an unemployed, 46-year-old mother, says that for her, bad things come in pairs.

“First my car that I used to get to work was stolen,” she says, as her hair hides her tears. She recounts that days later, her “apartment building was shut down because the landlord had so many code violations”. The landlord, whose activities she says were tantamount to being a slumlord, never updated his tenants and gave them only 24 hours to move out.

While the loss of the car might not be a stumbling block for some in major metropolitan areas, residents can’t expect much help from Kansas City’s Area Transportation Authority. KCATA’s director of business development, Frank White, says the jobs with livable wages aren’t easily accessible because “transit hasn’t been at the table when economic development conversations happen”. If the group that transports “the poor people” isn’t at the table when major decisions are made, those “poor people” won’t be guaranteed a voice.

Walled off by Troost Avenue, black people were historically restricted to the east side of the city by carefully constructed covenants that prevented them from moving into Kansas City’s Country Club district.

The homes of a burgeoning African American community were demolished to make room for Highway 71 over the course of decades, further impeding travel from black neighborhoods to the rest of the city. The predominantly white Country Club district remains one of the wealthiest neighborhoods in the United States, abutting one of the poorest areas of Kansas City.

Carl has been unemployed for nearly a year. Photograph: Jason Dailey for the Guardian

None of this, as James notes, took place “strictly by happenstance”.

The net result is that jobs deemed geographically close to black communities are are actually far if traveling by public transit. Shellie, who lives in the urban core, is about an 18-20 minute drive from Lenexa, Kansas, host of a new Amazon fulfillment center. Without a car, the the 18-20 minute drive becomes two hours and 12 minutes of bus-riding and walking, often without sidewalks.

Shellie, like Carl, finds odd jobs and public benefit programs that she can use to feed her child, and she leverages programs like LISC’s financial opportunity center to get her “financial house in order”.

“Everybody falls and hopefully everybody gets back,” she says. “But when a person falls, you need a little cushion so you can get yourself back up. But nowadays with a president that wants to cut the programs that help me get up, I live in fear every day that I can’t get up any more.”

Kansas City may be well and truly back on its feet – but no wonder James seems glum. The seemingly symbiotic relationship between structural racism and inequality, especially in education, “impedes [African Americans’] ability to be employed in gainful employment that provides a living wage or even decent wage,” says James, and it “stifles hope for hope” for African Americans.