“Departure of the Pilgrim Fathers From Delfshaven” (1620) by Adam Willaerts from the Rose-Marie and Eijk de Mol van Otterloo collection. Credit: Museum de Lakenhal Leiden.

On the 400th anniversary of the ship’s landing in Plymouth, Massachusetts, the commemoration will be more inclusive than in the past.

This article is part of our latest Museums special section, which focuses on the intersection of art and politics.

Paula Peters remembers the last major anniversary of the historic voyage in 1620 of the Mayflower from Plymouth, England, to Plymouth, Mass. It was in 1970. She was 12. “It did not go well,” recalled Ms. Peters, a member of the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe. Frank James, whose Wampanoag name was Wamsutta, was invited to give a speech, but was prevented from delivering it because the event’s organizers “didn’t like what he had to say.”

This year’s 400th anniversary promises to be different. “It will include all the things Frank James wanted to say and then some. It’s an opportunity to take our story out of the margins and onto an international platform,” said Ms. Peters, who through SmokeSygnals, a marketing and communications agency, curated and consulted for exhibitions and programs on both sides of the Atlantic. “What’s most important to stress is simply that we are still here.”

The Wampanoag Nation, encompassing the federally recognized Aquinnah and Mashpee tribes, are equal partners in the yearlong commemoration with Plymouth 400 in the United States, Mayflower 400 in the United Kingdom, and Leiden 400 in the Netherlands, umbrella groups for museums and organizations that are hosting Mayflower-related events in their respective regions.

“We are changing the narrative at this moment in history,” said Michele Pecoraro, executive director of Plymouth 400. Today, she said, “it is all about a shared history among four nations, that looks at it from that perspective probably for the first time. The Wampanoag involvement is a first. The Netherlands involvement is a first. Those added perspectives offer more of a balanced picture.”

Johanna C. Kardux, program director of American Studies at Leiden University, said this year’s initiative offered Native Americans a voice and cast the Pilgrims in a new light. Highlighting that the Pilgrims were migrants “provides a more complete perspective,” said Dr. Kardux, co-organizer of the forthcoming “Four Nations Commemoration, 1620-2020: The Pilgrims and the Politics of Memory” in Leiden.

Most Americans may know the basics of the Mayflower’s journey to the New World, but many are not aware that among the passengers who wanted to break away from the Church of England were a group of Pilgrims who went first to the Netherlands. In 1609, the city government of Leiden, which had a tradition of offering shelter to asylum seekers, granted some 100 English religious refugees permission to settle there. They stayed for more than a decade before some of them departed aboard the Speedwell in 1620. The first stop was Southampton, England, where they transferred to the Mayflower. Leiden Pilgrims, in fact, initiated the trans-Atlantic voyage.

“One of the fascinating aspects for me” said Michaël Roumen, executive director of Leiden 400, describing the Leiden of the early 1600s, “is as the Pilgrims walked cobblestone streets, they could be standing in the market next to a young Rembrandt.” (His school was a stone’s throw from where most Pilgrims lived.)

“There were religious refugees from all over Europe; there were public debates about predestination and civil liberties. It was a whirlpool of economic, academic and cultural dynamism,” Mr. Roumen said, that helped shape the New England political culture, especially the separation of church and state, one of the cornerstones of American democracy. Civil marriage was one of the innovations that the Pilgrims took with them from Holland to America. “The Pilgrims arrived in Leiden as religious refugees, tortured and imprisoned in their native England, but left as colonists,” he said. “It’s complicated.”

Throughout 2020, destinations in the United States, the United Kingdom. and Leiden will highlight their permanent exhibitions, walking tours, trails, historic sites and buildings, like the jail in Boston, England, where Pilgrims were held and tried, as well as a roster of special events, festivals, art exhibitions, public art installations, and activities like finding Pilgrim relatives at the “Ancestor Booth” in Leiden, where visitors can explore their heritage. Nine U.S. presidents are considered descendants of a Leiden Mayflower passenger, including Franklin Delano Roosevelt, both George H.W. Bush and George W. Bush; roughly 30 million people can claim a connection to a Mayflower descendant.)

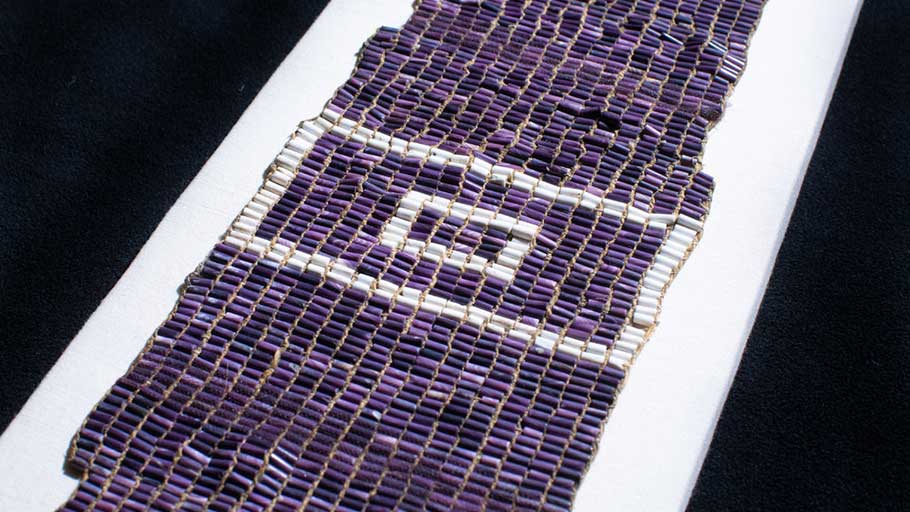

A detail of a belt created by members of the Wampanoag nation is displayed at the British Museum in London. Credit: Suzanne Plunkett for The New York Times.

Here is a sampling of exhibitions:

The United States

“‘Our’ Story: 400 Years of Wampanoag History” is a traveling exhibition that recounts the story of the Wampanoags with stops at museums, libraries, schools and businesses in Massachusetts through 2020. “It’s a nice mix of historical and modern day information,” said Ms. Pecoraro of Plymouth 400. “It’s significant having native people tell their history, their story, in their voice.”

Seven chapters trace historical developments, from the 1614 capture of Native American men by a European explorer to sell as slaves in Spain, to a trend embraced by the American Indian Movement for tribes to observe a National Day of Mourning instead of Thanksgiving.

The United Kingdom

“Wampum: Stories from the Shells of Native America,” April 3 to Oct. 24. The traveling exhibition will stop at different Mayflower linked places. The centerpiece will be a wampum belt commissioned for the show made of some 5,000 handcrafted beads by more than 100 Wampanoag artisans.One aim is to raise awareness about the missing wampum belt from the 17th century belonging to a Wampanoag chief known as Metacom. The belt, said to have been about nine feet long and nine inches wide, was taken and sent to England during what was known as King Philip’s War between Native Americans and colonists, Ms. Peters said. “There’s the hope that through the exposure, we will be led to our ancestors’ Wampum belt, lost for more than three centuries,” she said.

The Box, a new cultural and heritage complex, will open in Plymouth with “Legend and Legacy” on May 16 through Sept. 18, 2021. The exhibition will explore the origins of the Mayflower journey, the way it has been commemorated through generations, and the conflict with and the impact of colonization on the indigenous population. The show will feature some 300 items from 100 museums, libraries and archives from around the world. Rare objects include 17th century books, engravings and artifacts, like the first Bible to be printed in America and a document that gave the Mayflower colonists English permission to settle in America.

“Departure of the Pilgrim Fathers From Delfshaven” (1620) by Adam Willaerts from the Rose-Marie and Eijk de Mol van Otterloo collection. Credit: Museum de Lakenhal Leiden

The Netherlands

“Pilgrims to America — And the Limits of Freedom,” March 27 to July 12 at the Museum De Lakenhal. Almost 200 paintings, engravings, books, maps, muskets, pots and pans — original works of art and everyday items — detail the Pilgrims’ journey from 1604 to 1621. Interactive experiences include magnets with words like “freedom” and “repression” to inspire visitors to create poems.

“First Americans: Honouring Indigenous Resilience and Creativity” — Museum Volkenkunde (National Museum of World Cultures), May 15 through July 24, 2021, will feature about 60 Native American works: paintings, photographs, textiles, jewelry, and fashion pieces, some commissioned for the exhibition. “More than 12 living artists contributed,” said Henrietta Lidchi, the museum’s chief curator, including Tulsa-based Yatika Starr Fields, who painted a huge mural “Accommodating strength, Our land, Our hearts” in public during seven days at the museum, and Phoenix-based print maker Jacob Meders, whose works will reflect early European depictions and stereotypes of indigenous people.

This article was originally published by The New York Times.