By Prof. Verene Shepherd (Centre for Reparation Research) and Ahmed Reid (City University of New York) —

In a New York Times article by Stephen Castle of December 27, 2014, ironically the anniversary of the outbreak of the war led by Samuel Sharpe that hastened legislative Emancipation by the British, we learned that after a financial crash in 1720, called the South Sea Bubble, the British government was forced to undertake a bailout that eventually left several million pounds of debt on its books. In 2014, Britons were still paying interest on a small part of that obligation. But prompted by record low interest rates, the British government announced plans to pay off some of the debts it racked up over hundreds of years, dating as far back as the South Sea Bubble that included borrowing that may have been used to compensate enslavers when slavery was abolished.

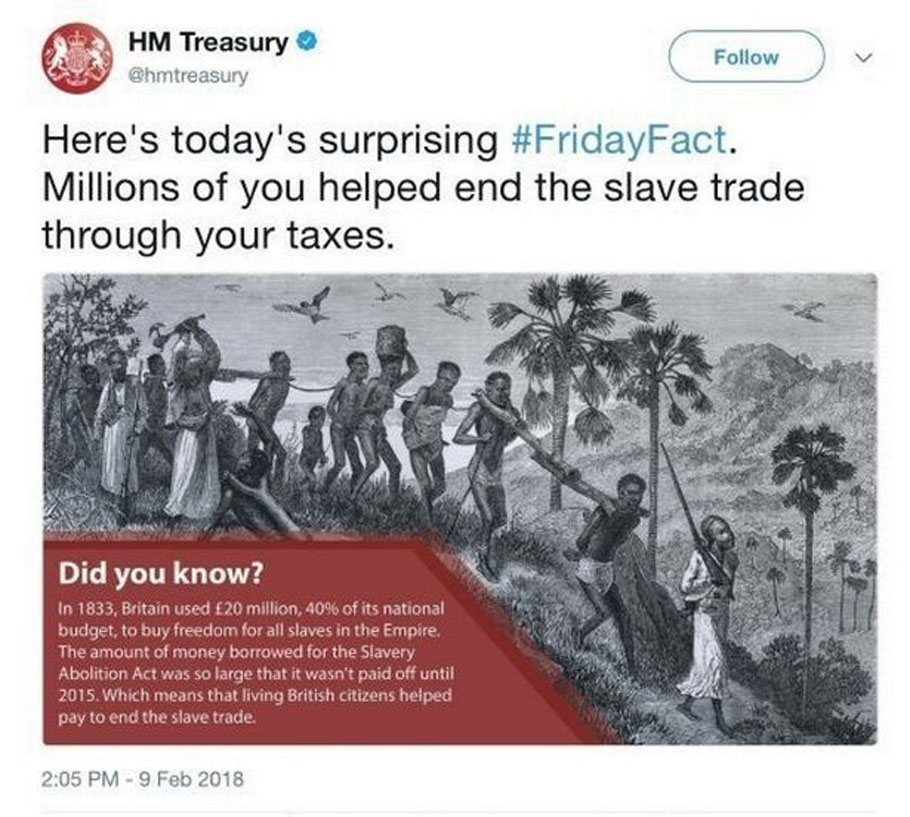

Then on 9th February, a tweet from Her Majesty’s Treasury (UK) revealed that in February 2015 the British Government completed repaying the loan of £20 million (or £17billion in today’s money) that it borrowed to pay the enslavers compensation so that they would agree to the Emancipation of the enslaved peoples in 1834. Positioned as a “Did You know?”, the tweet claimed that “In 1833, Britain used £20 million, 40% of its national budget, to buy freedom for all slaves in the Empire. The amount of money borrowed for the Slavery Abolition Act was so large that it wasn’t paid off until 2015. Which means that living British citizens helped pay to end the slave trade.”

Screenshot of the Treasury tweet, which has now been deleted.

Of course, living Britons did not help to “end the slave trade” (the Abolition Act was passed in 1807); and it would have been more accurate to say that the money was used to line the pockets of the enslavers and that it afforded them access to large sums of capital that stimulated a second industrial revolution rather than suggest that it somehow enabled a benevolent act of Emancipation. Furthermore, the use of the image of a “slave coffle” on the tweet that reminds so many of us of the dislocation, murder, exploitation and dehumanization of our ancestors and the cruelty of colonizers, was distasteful and unsuitable for the news being conveyed. Not to be ignored is the suggestion that it was the size of the loan that made it take so long to be paid off, when we now know that it was because of the continuous capitalization of the loan, the last of which occurred in 1927 by the then Chancellor of the Exchequer, Winston Churchill.

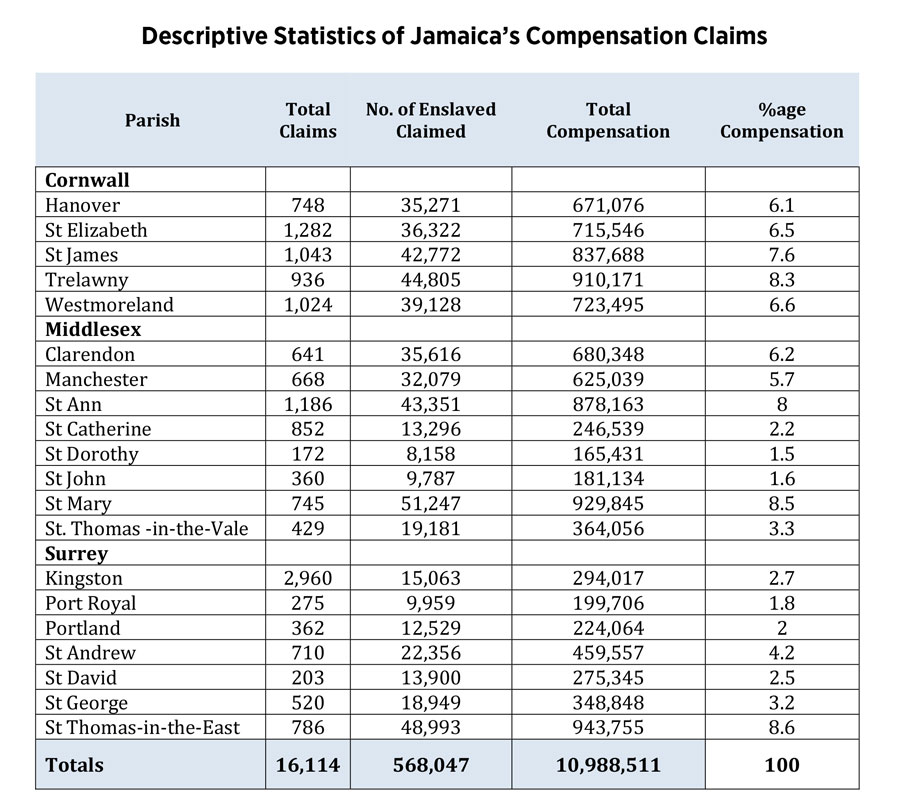

While many remain outraged at the revelation that taxpayers in Britain, including hundreds of thousands of Jamaicans and other Caribbean nationals whose ancestors were enslaved by the British, and whose labour helped to build Britain, helped to pay the interest payments on the loan that paid the enslavers, others are using the opportunity to revisit the compensation pay-out and to renew the call for reparation for the injustice of compensating enslavers but not the enslaved. Jamaicans may have read the result of the research by the team from University College, London that showed that 50% of the £20 million compensation money stayed in the UK, and was distributed among 3,000 people. The other 50% was distributed among planters in the colonies. Indeed, 16, 114 claims were filed for enslaved people in Jamaica by enslavers in the USA, UK and throughout the Atlantic World, totalling approximately £10.98 million pounds.

Of those 16,114 claims, 13,000 were filed by enslavers resident in Jamaica and their pay-out was £4.10 million or £3 billion in today’s money. It is interesting to peruse the parish breakdown of the compensation recipients in Jamaica. It will be seen that two parishes that at varying times have been labeled the poorest parishes in Jamaica, St Mary and St Thomas (East), had some of the wealthiest planters in the 19th century, representing 8.5% and 8.6% respectively of the total compensation package. Think what difference that money could have made to these two parishes!

When converted to modern equivalences, the £929,845 paid to enslavers who filed claims for enslaved people in St. Mary would amount to a mind-boggling sum of £711 million. For St. Thomas, enslavers filed 786 claims for 48,993 enslaved Africans and received a largesse of £943,755 or £721 million in today’s money. Of the sums mentioned above, we know that enslavers invested in cultural institutions, built palatial country houses across Britain, invested in the railroad industry among other commercial ventures, and invested throughout the Empire. Britain, and the descendants of those enslavers continue to benefit today from those investments. And what did enslaved people from St. Mary and St. Thomas get? What kind of investments did they make to realize their hopes and expectations of freedom, and more importantly, to secure a future for their offspring? We all know the answers to these rhetorical questions; and this is why the reparatory justice movement is framed within the discourse of development. Having enriched British planters who prospered on the backs of their ancestors, St Mary and St Thomas (former St Thomas in the East) surely need an injection of capital to improve the conditions of their long-suffering citizens, and Britain has an obligation to live up to her responsibilities. As Sir Ellis Clarke, who was the Trinidadian Government’s UN representative to a sub-committee of the Committee on Colonialism in 1964 said: “An administering power…is not entitled to extract for centuries all that can be got out of a colony and when that has been done to relieve itself of its obligations by the conferment of a formal but meaningless – meaningless because it cannot possibly be supported – political independence. Justice requires that reparation be made to the country that has suffered the ravages of colonialism before that country is expected to face up to the problems and difficulties that will inevitably beset it upon independence.”

When converted to modern equivalences, the £929,845 paid to enslavers who filed claims for enslaved people in St. Mary would amount to a mind-boggling sum of £711 million. For St. Thomas, enslavers filed 786 claims for 48,993 enslaved Africans and received a largesse of £943,755 or £721 million in today’s money. Of the sums mentioned above, we know that enslavers invested in cultural institutions, built palatial country houses across Britain, invested in the railroad industry among other commercial ventures, and invested throughout the Empire. Britain, and the descendants of those enslavers continue to benefit today from those investments. And what did enslaved people from St. Mary and St. Thomas get? What kind of investments did they make to realize their hopes and expectations of freedom, and more importantly, to secure a future for their offspring? We all know the answers to these rhetorical questions; and this is why the reparatory justice movement is framed within the discourse of development. Having enriched British planters who prospered on the backs of their ancestors, St Mary and St Thomas (former St Thomas in the East) surely need an injection of capital to improve the conditions of their long-suffering citizens, and Britain has an obligation to live up to her responsibilities. As Sir Ellis Clarke, who was the Trinidadian Government’s UN representative to a sub-committee of the Committee on Colonialism in 1964 said: “An administering power…is not entitled to extract for centuries all that can be got out of a colony and when that has been done to relieve itself of its obligations by the conferment of a formal but meaningless – meaningless because it cannot possibly be supported – political independence. Justice requires that reparation be made to the country that has suffered the ravages of colonialism before that country is expected to face up to the problems and difficulties that will inevitably beset it upon independence.”