It didn’t end there. Photographer: Rischgitz/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

The issue of reparations for African Americans is, of course, full of more moral and historical issues than one column, even by someone with much greater understanding and deeper knowledge than me, could ever resolve. But since the proposal is now being taken seriously, it’s worth thinking about the economics of how it could and should work.

The idea of compensating the descendants of American slaves is an old one. More recently, writers like Ta-Nehisi Coates have argued persuasively that systematic oppression after the end of slavery — segregation, housing discrimination and violence — deserve reparations as well. Democratic presidential candidates such as Julian Castro, Kamala Harris and Elizabeth Warren have endorsed the idea in principle, though the specifics are still hazy. Even conservative columnist David Brooks has joined the pro-reparations chorus.

Doubtless opponents of reparations will marshal their own arguments. They will ask, for example, why Americans whose ancestors played no direct role in slavery or Jim Crow — especially Mexican Americans, Japanese Americans and others whose own ancestors suffered systematic persecution — should be required to pay.

Such points can’t be dismissed, but I find the arguments in favor of reparations persuasive. General William T. Sherman, who liberated much of the American South, never delivered on his promise to give former slaves Southern land confiscated during the Civil War; reparations would, in a way, be a delayed fulfillment of that pledge. No less important, it would provide an opportunity to publicly make amends for many decades of segregation and other racist policy, demonstrating to black Americans that the country is on their side, and to all Americans that their country is a moral one.

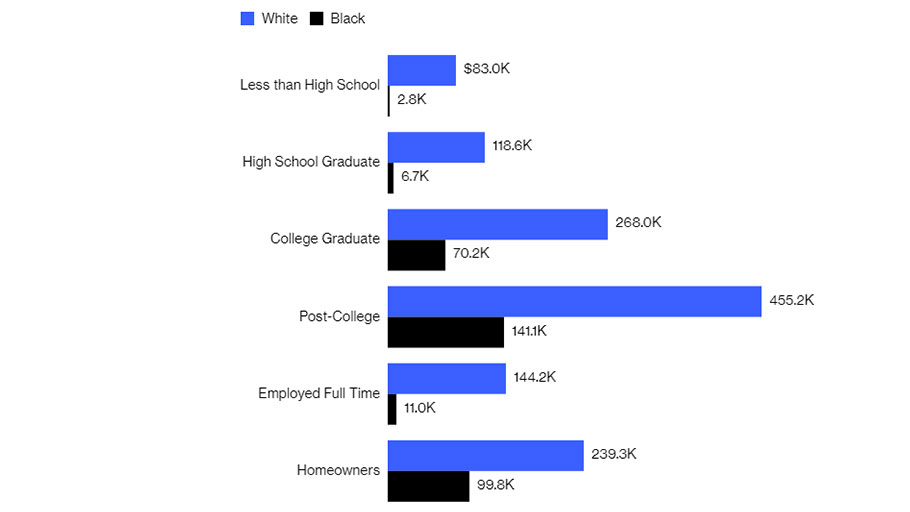

But this leaves the question of what the goal of reparations would actually be. One obvious target is to reduce the persistent black-white wealth gap:

A Most Stubborn Gap

Estimated median household net worth in 2014

Source: “What We Get Wrong About Closing the Racial Wealth Gap,” William Darity Jr. et al. Samuel DuBois Cook Center on Social Equity

This could be done by simply transferring wealth to the descendants of American slaves. Though some, like Senator Bernie Sanders, have deridedthis approach as “writing out a check,” it has the virtue of being simple and quantifiable — each person knows how much they’re getting, and how much other people are getting, making it easier to ensure that the system is fair.

The simplest suggestion for a wealth transfer is the idea of baby bonds, advanced by economists William Darity and Darrick Hamilton. If done as a form of reparations, the program would simply endow every black child with a government trust fund, worth perhaps $21,000 to $47,000. The proposal would have to be modified to give some money to the parents, grandparents and other family members of the recipients, but that’s the basic idea.

A thorny question, however, is when to let the recipients liquidate the funds. If they’re able to withdraw all the money at once, many will be quickly taken in by scams, or by money managers charging exorbitant fees. Part of being poor is not having much experience managing wealth, which makes recipients of reparations likely to earn poor returns. On the other hand, if the program allows bonds to be liquidated only slowly, it will be frustrate poor black people who need money immediately to pay for medical bills, home improvements, or other pressing needs.

One alternative idea is to allow recipients to withdraw their reparations money any time they like, but to put the money in a government-managed social wealth fund. This fund would put black people’s wealth into low-cost diversified portfolios — index funds, real estate, bonds. It would charge very low or no fees. And it would take care of things like risk allocation and matching the investments’ time horizon to expected withdrawals, functions that would be difficult for unsophisticated investors to understand. The fund could also offer free financial advice to reparations recipients.

This would be an equitable and efficient solution — a modern-day equivalent to the “40 acres and a mule” Sherman promised. But there’s a good chance it wouldn’t be a permanent one. Black Americans tend to earn less than whites, so they have less money to save in the first place.. A recent study by economists Dionissi Aliprantis and Daniel Carroll found that the income gap is by far the biggest reason that the wealth gap has persisted so stubbornly.

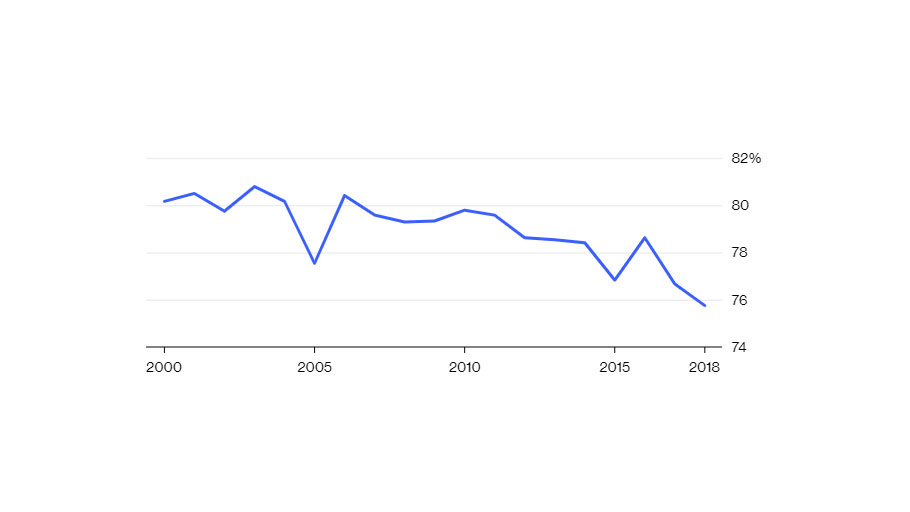

Reparations, therefore, should also take steps to reduce the income gap. Part of this could include job provision programs in poor black areas where unemployment is high. President Bill Clinton’s Opportunity Zones proved that this approach can work. But even this won’t be enough, since black people tend to earn lower wages even when employed full-time:

Falling Behind

Ratio of black to white median weekly earnings

Falling Behind. Ratio of black to white median weekly earnings. Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

So reparations should also include policies to help black people get higher-paying jobs. These could include college scholarships, as well as stricter enforcement of the Fair Housing Act in order to ensure that black families have better access to high-income neighborhoods and schools. Finally, it could include a large-scale effort to clean up the toxic waste that pollutes many black neighborhoods. These are all worthy policies in any case. Making them part of a large-scale reparations program would add moral force and political impetus.

So reparations are very doable, but the task is not simple. Crafting policies to permanently reduce the black-white wealth gap will require ingenuity and a sustained, multi-pronged approach.