Openly talking about reparations for the descendants of enslaved men and women is a notable shift for Democrats. But the conversation still lacks substance.

A new 2020 litmus test has arrived for Democrats running for president: Do they support reparations?

It marks a turn in a primary contest in which black voters are expected to play a significant role. That the attention to reparations has become so prominent speaks to a series of changes that have occurred in recent years — namely, the increased academic understanding of and public attention to the ways a history of slavery and discrimination has fueled disparities like the racial wealth gap, which shows that the median white household is 10 times wealthier than the median black one.

These changes, coupled with a wave of grassroots activism around racial inequality and economic injustice, have helped produce a shift in mainstream attention to reparations. That attention intensified after some 2020 Democratic candidates commented on reparations to the New York Times and the Washington Post last month.

So far, a handful of candidates have expressed some level of support for reparations: Sens. Kamala Harris (D-CA) and Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), and former Housing and Urban Development Secretary Julián Castro have called the issue important or acknowledged how history supports calls for restitution.

Sen. Cory Booker (D-NJ) has been running on a policy that would help close the racial wealth gap, while Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) has declined to support reparations but argues that his focus on policies helping distressed communities in general would particularly aid black communities.

The candidate most fervently backing reparations is Marianne Williamson, a self-help guru and spiritual adviser who wants to set aside $100 billion to $500 billion for a reparations program.

Several high-profile candidates have acknowledged the damages of slavery; the century of legalized oppression, terrorism, and disenfranchisement that followed; and how the vestiges of those systems remain embedded in society in practices such as mass incarceration.

Some candidates have also noted that reparations — the process of apologizing and providing restitution to those harmed by slavery and its legacy — would serve as payment for a debt America has yet to truly acknowledge 150 years after emancipation.

But they’ve stopped short of actually calling for reparations programs. Instead, experts say that some candidates have muddied the waters by framing universal programs that would help black communities as a form of reparations — which they aren’t.

The discussion has touched on a longstanding debate about what the United States owes to the descendants of enslaved men and women — a population that has been systematically denied wealth and opportunity in a country built with the stolen labor of their ancestors.

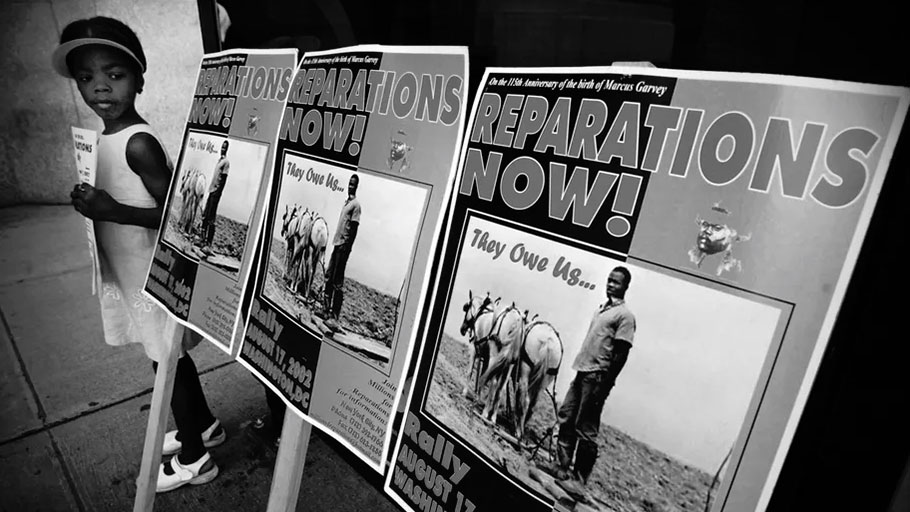

A young girl attends a slavery reparations protest outside of the New York Life Insurance Company offices on August 9, 2002, in New York City. Mario Tama/Getty Images

Surveys of black voters in recent years have found that this group is dealing with high levels of racial anxiety and are looking for candidates who can speak directly to issues of race and justice, including economic justice. Reparations have not been listed as a priority by black Americans in recent polling, but the current debate could change that. The debate also provides important insight into how candidates talk about race and inequality.

“I think the reparations discussion helps to open up a broader conversation of about the fact that centuries of discriminatory policies have prevented mobility among black communities,” says Adrianne Shropshire, the executive director of BlackPAC, a group that works to engage and mobilize black voters. Still, she says that how the candidates have discussed the issue so far “lacks substance.”

The mere willingness of some Democratic candidates to say they support reparations reflects a shift from recent years. President Barack Obama did not endorse reparations or support creating a reparations program. In 2016, Sanders and Hillary Clinton, the eventual Democratic nominee, also did not support reparations. (Sanders in particular was criticized for focusing his opposition on the fact that reparations were “divisive” and would not pass Congress.)

The issue was, and still is, politically unpopular, particularly among white voters.

It’s clear that the Democratic Party is being pushed to have difficult conversations about race and racism — but where did this conversation about reparations come from? And what does it say about the party as a whole?

How the idea of reparations entered the national conversation

Proponents of reparations say their argument is straightforward: America — through more than 200 years of slavery — built its wealth through the labor and very existence of the black men and women enslaved in chattel bondage.

The century that followed emancipation saw the creation of policies that discriminated against black people and largely excluded them from wealth building, creating an inherited disadvantage for future generations.

Reparations, its supporters argue, provides redress for both the original sin of slavery and America’s subsequent failure to address generations’ worth of accrued disadvantage in black communities.

Though the idea of reparations has been around since the Civil War, the current debate about reparations moved further into the national popular conversation in 2014 when journalist Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote “The Case for Reparations” for the Atlantic, arguing that reparations would drive a “national reckoning that would lead to spiritual renewal.”

At the time, it was a provocative argument — clearly intended to prompt a conversation about the moral necessity of reparations. Coates’s article is well worth reading in full, but an important part of his argument is about housing policy and wealth, two of the most visible ways the inherited disadvantage of black people has manifested.

Coates explains:

Black families, regardless of income, are significantly less wealthy than white families. The Pew Research Center estimates that white households are worth roughly 20 times as much as black households, and that whereas only 15 percent of whites have zero or negative wealth, more than a third of blacks do. Effectively, the black family in America is working without a safety net. When financial calamity strikes — a medical emergency, divorce, job loss — the fall is precipitous.

And just as black families of all incomes remain handicapped by a lack of wealth, so too do they remain handicapped by their restricted choice of neighborhood. Black people with upper-middle-class incomes do not generally live in upper-middle-class neighborhoods. [New York University sociologist Patrick] Sharkey’s research shows that black families making $100,000 typically live in the kinds of neighborhoods inhabited by white families making $30,000. “Blacks and whites inhabit such different neighborhoods,” Sharkey writes, “that it is not possible to compare the economic outcomes of black and white children.”

Coates openly acknowledges that his case follows a larger academic movement that has existed for decades, one that in recent years has been further advanced by economists like Duke University’s William Darity and the New School’s Darrick Hamilton — both of whom look at the relationship between racial inequality, wealth, and the need for reparations.

More broadly, a growing body of research has outlined the extent of the disparities between black and white Americans in terms of income, health outcomes, quality of schooling, homeownership — and perhaps most significantly for economists, a continued decline in wealth among black Americans.

African Americans protest for equal rights during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on August 28, 1963. Universal History Archive/Getty Images

Collectively, the disparities, and the argument that they are the result of a history of slavery and racial discrimination, have fueled a new wave of activism around racial inequality and increased calls for reparations from black activists. In 2016, the Movement for Black Lives, a coalition of dozens of activist groups working on racial justice, included reparations in its policy platform.

More recently, online calls for reparations have been driven by a grassroots movement of black activists specifically advocating on the behalf of American descendants of slavery (or ADOS, as the movement is called).

In an interview with Vox, Antonio Moore and Yvette Carnell, the co-founders of and most prominent voices in the current ADOS movement, explain that they believe that ADOS should be seen as a specific identity.

On its website, the movement says that it “seeks to reclaim/restore the critical national character of the African American identity and experience, one grounded in our group’s unique lineage.”

When it comes to reparations, Moore says, “we’re not having an abstract conversation about what whiteness and blackness makes you feel. We’re having a very detailed conversation about what the data means for black people.”

“We are talking about repairing black communities,” he adds.

On Twitter, and through online radio programs and YouTube channels, Moore and Carnell have argued that policy — and politicians — need to focus more on specific issues affecting black Americans descended from slavery in the US. They call for reparations as part of a larger “black agenda” that looks at things like ending mass incarceration, investing in historically black colleges and universities, and increasing federal investment in small businesses.

But this movement has also faced criticism — not for its call for reparations, but for how it discusses immigration and black identity. Critics have argued that some ADOS activists are openly xenophobic and that the movement endorses an unnecessarily limited definition of “blackness,” dismissing the ways slavery and colonization have affected other groups in the African diaspora.

When I asked Moore and Carnell to respond to these criticisms, they said that the movement was “seeking to establish that there was a specific debt to a specific group of people.”

A growing body of research argues that reparations should happen

Taking a step back, it’s helpful to look at the arguments supporting reparations that have been laid out in recent years, especially since these proposals differ in a lot of ways from how the 2020 candidates have discussed reparations.

While it is true that “reparations” as a concept can refer to multiple things, in this specific context, it refers to demands for a formal apology for centuries of slavery and discrimination and subsequent restitution for black people descended from men and women enslaved in the United States.

This debate is by no means new. Demands for reparations were made during the Civil War through Union Army Gen. William T. Sherman’s Special Field Order 15 issued in January 1865.

That proposal called for a massive land redistribution giving roughly 40,000 formerly enslaved people 40 acres of land each, the basis for the “40 acres and a mule” terminology that is often invoked in modern discussions of reparations. However, this redistribution was short-lived, with President Andrew Johnson rescinding the order and returning the land to white owners later that year.

There are examples of individual people and some coalitions seeking compensation for their enslavement in the decades following the Civil War, but the era of Reconstruction that followed did not see any concerted federal effort to apologize for slavery or provide any sort of payment to formerly enslaved people. Congressional bills seeking financial compensation never received any serious legislative action.

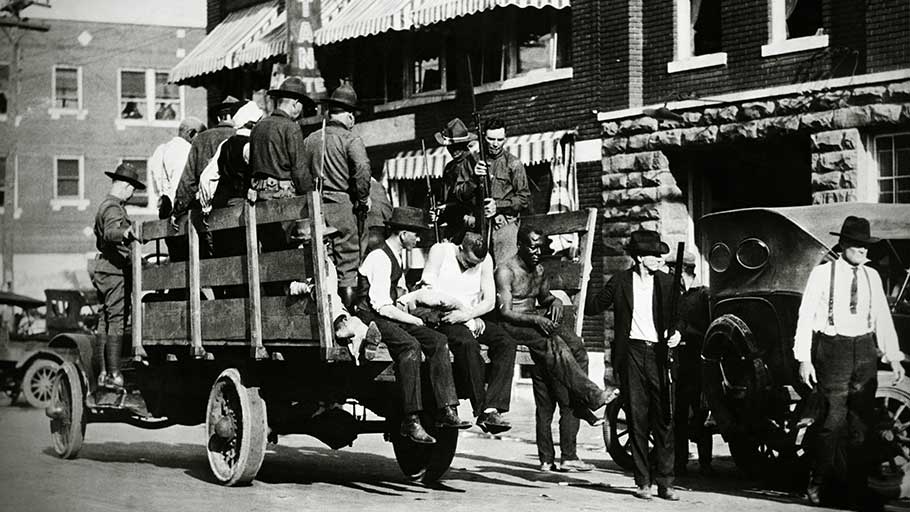

After the Civil War, systems of convict leasing and sharecropping continued to exploit black labor while allowing white society to hoard the wealth created by that work. Communities that later succeeded in building black wealth — places like Tulsa, Oklahoma’s “Black Wall Street” in the early 1920s — were met with outright violence or were subjected to “whitecapping,” a type of threat used to scare black people into relocating.

The “Tulsa race massacre” of 1921 spanned two days when mobs of white rioters attacked local black residents and businesses in the Greenwood District of Tulsa, Oklahoma. — Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis; Oklahoma Historical Society/Getty Images

The “Tulsa race massacre” of 1921 spanned two days when mobs of white rioters attacked local black residents and businesses in the Greenwood District of Tulsa, Oklahoma. — Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis; Oklahoma Historical Society/Getty Images

The “Tulsa race massacre” of 1921 spanned two days when mobs of white rioters attacked local black residents and businesses in the Greenwood District of Tulsa, Oklahoma. — Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis; Oklahoma Historical Society/Getty Images

Well into the 20th century, a combination of federal policy and private industry regulations allowed not only for Jim Crow in the South but for the limited ability of black people to access wealth-building programs like the New Deal and the GI Bill. Black people were also exposed to discriminatory housing practices like redlining, and pervasive residential and educational segregation further compounded earlier injustices.

In other words, slavery created a system where black people were forced to provide the labor that built a country they were virtually excluded from participating in. The end of slavery did not produce an effort to fully incorporate this group into American life, but instead ushered in a century of exclusion through federal policy — an exclusion that made black people an American underclass.

So what would reparations actually look like?

To remedy the specific harms of this large-scale dehumanization and denial of wealth, advocates say a large-scale investment — one that comes with an apology for the harms committed and a commitment to further mending these harms through payments and directly targeted policies — is needed.

There isn’t a single model for what a reparations plan would look like. But it is helpful to look at the work of economists, like Duke University’s Darity and the New School’s Hamilton, who see reparations as a crucial way to address a significant gap in wealth between black and white Americans.

“The major financial objective of a reparations program is to close the racial wealth gap,” Darity tells Vox. The universal programs that some candidates have advanced “won’t come close to that,” he says.

“There are three goals of a reparations program,” he explains. “The first is acknowledgment, the second is redress, and the third goal is closure.” So far, candidates have largely focused on the first point.

Darity has been researching reparations and America’s racial wealth gap for years, providing more information on how far black Americans’ wealth lags behind other groups and on how slavery and systemic discrimination played a role in creating this situation.

When reparations are discussed, the biggest questions raised revolve around what a reparations program would look like, who would benefit, who would pay, and how it would be funded. The best way to determine this would be for the government to formally study reparations. Until that happens, it is helpful to look at Darity’s work, which provides one possible road map for reparations and addresses some of the above questions.

Looking at who would qualify for reparations, Darity argues that restitution should be limited to people who can trace their roots back to at least one ancestor enslaved in the US, adding that claimants must also have identified as black, African American, colored, or Negro on legal and government documents at least 10 years before a reparations program takes effect.

When it comes to what a reparations plan would look like, Darity has argued that exclusively offering cash payments without addressing the underlying structures that have restricted black people from building wealth would fail to correct the issue.

Instead, he has looked at what he calls a “portfolio of reparations”: a combination of individual payments and race-targeted proposals like vouchers for financial asset building, free medical insurance or free college education for black people, or a trust fund exclusively for black Americans.

He also calls for an education program that would teach Americans the complete story of slavery and its aftereffects, which he says would help the country understand the harms done. (To read more of Darity’s work, these two papers are a good start.)

Darity is currently working on a book about reparations in America, and he has argued the US would need to spend several trillion dollars to begin its process of atonement for centuries of bondage, violence, and discrimination against black Americans (estimates from other economists and researchers range from $6.4 trillion to $14 trillion).

“The damages to the collective well-being of black people have been enormous,” Darity has noted in his research. “Correspondingly, so is the appropriate bill.”

While experts do not exclusively focus on the direct cash payments framework, that practice does have some precedent. Vox’s Dylan Matthews explained this in 2014 when looking at previous reparations programs in the US and other countries:

The six clearest antecedent programs are those set up by Germany to compensate victims of the Holocaust, by South Africa to compensate victims of apartheid, by the US to compensate victims of Japanese internment during World War II, by the state of North Carolina to compensate victims of its forced sterilization programs in the mid-20th century, by the federal government to compensate victims of the Tuskegee experiment, and by Florida to compensate victims of the Rosewood race riot of 1923.

Matthews notes that the Germany program, which gave more than $7 billion to Israel but largely focused on providing individual reparations to survivors of the Holocaust, is perhaps the closest analogue to a reparations program for descendants of enslaved people in the US. That program had paid out nearly $89 billion as of 2012, less than half of the more than $240 billion the Israeli government assessed as the economic cost the Jewish people suffered from the Holocaust.

Here’s what Democrats are actually proposing — and not all of it is technically “reparations”

Coming back to the Democratic primary, we should be clear and note that none of the prominent candidates are talking about the policies or proposals outlined above. The New York Times’s Astead Herndon and the Washington Post’s Jeff Stein first got candidates on the record on reparations in February, but here’s where things stand now.

Sen. Kamala Harris

Harris expressed support for reparations early in February but has since given conflicting accounts of her exact stance on passing race-specific reparations policies, telling the Grio, a black news outlet, “If you look at the reality of who will benefit from certain policies, when you take into account that they are not starting on equal footing, it will directly benefit black children, black families, black homes-owners because the disparities are so significant.”

She touts the LIFT Act, a tax plan that would provide a tax credit to working singles making $50,000 or less and families making $100,000 or less, expanding the safety net for the middle class. Harris argues that this policy, which Darity argues is far too small and not targeted enough to qualify as reparations, would particularly benefit black families. (You can read an analysis of the LIFT Act and other anti-poverty programs by Dylan Matthews here.)

Sen. Elizabeth Warren

Warren, who has said that Native Americans should also be “part of the conversation” on reparations, has not offered a specific reparations policy but has pointed to the importance of several of her proposals, including her American Housing and Economic Mobility Act.

The act would create a housing program that would offer special financial aid to first-time homebuyers in communities affected by redlining, a form of housing discrimination that classified predominantly black communities and homebuyers as “hazardous” and undesirable, a designation that led to extremely high — if not outright prohibitive — costs of loans to black homebuyers.

Sen. Kamala Harris (D-CA) (C) talks with a member of her staff during a meeting with leaders from historically black colleges and universities on February 7, 2019, in Washington, DC. — Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) speaks to the media at the New Hampshire Democratic Party’s 60th annual McIntyre-Shaheen 100 Club Dinner in Manchester on February 22, 2019. Nathan Klima/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

Warren’s plan has been praised by some economists who argue that it could put a “substantive dent” in the racial wealth gap, but again, the program is not targeted enoughto be called reparations. Last week, Warren declined to say if she supports financial compensation for the descendants of the formerly enslaved, telling CNN, “We need to address the fact that in this country, we built great fortunes and wealth on the backs of slaves and we need to address that head-on — we need to have that national conversation.”

Julián Castro, former housing and urban development secretary

Castro says that reparations are a discussion “worth having” and recently criticized those dismissing direct financial payments to the descendants of slaves. So far, he has not offered a proposal for a reparations program but has instead expressed support for a task force that could study why reparations are needed and how to go about implementing them.

This idea is similar to HR 40, legislation calling for a formal study of reparations for African Americans that was repeatedly introduced (but never passed) in the House of Representatives by former Rep. John Conyers for close to three decades. (Texas Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee reintroduced the bill in January.)

Sen. Cory Booker

Booker has proposed a “baby bonds” program that would give every child a savings account, with federal contributions to the account increasing as parental income decreases. He specifically cites this program as addressing the racial wealth gap. Darity and Hamilton have backed similar programs, and argue that the proposal is one of the more powerful race-neutral ways to help close the racial wealth gap for future generations.

But unlike Booker’s program, the economists prefer that baby bonds be tied to parental wealth, not income. A spokesperson for Booker recently told NPR that the program could be seen “as a form of reparations” because its focus on low-income families would disproportionately help black children. However, this still does not meet the race-specific standard needed to qualify as reparations.

Sen. Bernie Sanders

Sanders, who was criticized for opposing reparations during the 2016 presidential race and recently said that “there are better ways to do that than just writing out a check” when asked about direct cash payments to the descendants of enslaved people, has asked his competitors to clarify what they mean by “reparations.”

He argues that programs aimed at the poor more broadly can help address inequality. While his support for universal programs over specific race-based ones is in line with many of the Democrats competing against him, Sanders has faced criticism from those who see his comments as part of a larger difficulty in discussing race.

Democratic presidential candidate Julián Castro arrives at an event hosted by the Boone County Democrats at the Livery Deli on February 23, 2019, in Boone, Iowa. — Stephen Maturen/Getty Images

Sen. Cory Booker (D-NJ, left) and Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT, right) march with the South Carolina NAACP chapter during the commemoration of Martin Luther King Jr. Day on January 21, 2019, in Columbia, South Carolina. — Sean Rayford/Getty Images

Sanders has also endorsed Rep. Jim Clyburn’s (D-SC) 10/20/30 anti-poverty program, which calls for at least 10 percent of some federal resources be invested in communities where 20 percent or more of the population has been below the poverty line for 30 years.

Will reparations actually happen?

It’s clear there are lots of priorities in the Democratic Party, from climate change to universal health care to racial justice. Whether Democrats are enthusiastically or reluctantly dipping their toe into the discussion around reparations, it is certainly now part of the conversation.

Rhetorically, it’s a big shift — the fact that HR 40, merely a mandate to study the idea of reparations, has languished without a vote for decades shows that there’s long been little political will to look at reparations at the federal level.

The fact that some candidates are not openly dismissing reparations shows progress in their attention to race and racism, but it is also true that as of now, they aren’t really discussing reparations as a policy issue.

Critics of the conversation have argued that reparations are simply not possible, pointing to polls have shown that there’s limited support for reparations, especially among white Americans. A 2016 Marist poll found that 68 percent of American adults oppose providing restitution to the descendants of enslaved Africans, and that white Americans are far more likely than black Americans to oppose reparations.

A 2014 YouGov poll found similar results, and a majority of white respondents in that poll said that the legacy of slavery was “not a factor at all” in the wealth gap between black and white Americans, something that historical data refutes.

In recent weeks, some political commentators have argued that reparations are too complicated to execute, would strain race relations and be too divisive, and are too costly to hand out. Other critics argue that reparations are a slippery slope, opening the door to other minority groups demanding redress for historical injustices. As George Will put it in the Washington Post last week, “There must be some statute of limitations to close the books on attempts to assign guilt across many generations to many categories of offenders.”

Another argument that has been particularly frequent in conservative circles is that America is just too far removed from slavery to justify a reparations program.

“Paying reparations for slavery is a terrible idea because there is no one to pay reparations and no one to pay them to,” a group of editors at the conservative news outlet National Review recently argued.

These are not new complaints. But activists and economists who have been involved in reparations advocacy and research argue that in a country where civil rights and anti-discrimination policies have never been popular at the moment of their enactment, these arguments reflect both a limited political imagination and a lack of awareness of recent research into reparations.

Beyond that, proponents of reparations argue the debate shows a continued refusal to acknowledge that slavery and what came after it — failed promises of Reconstruction and decades of Jim Crow policies, exclusion from federal programs, redlining, and a large gap between white and black wealth — are the result of a debt that the American government has never truly addressed.

If political candidates discussing reparations are serious, they “should move away from the language of emphasizing that the problem of the racial wealth gap can be solved by universal policy,” Darity says. “They have to be willing to say that they endorse a large-scale program that would be specifically targeted at the historical injustices that have confronted black descendants of those enslaved in the United States.”

This article was originally published by VOX.