New books investigate the brutality of the internal slave trade by focusing on a single firm, Franklin and Armfield, and examine the role of white women in enslaving Black people.

In the decades after the Civil War, when white southerners created the mythology of the Lost Cause, they depicted slavery as a benign institution that uplifted and protected a childlike people. But even the most creative nostalgists for the Old South struggled to justify the slave trade. For Mary Norcott Bryan of North Carolina, who in A Grandmother’s Recollection of Dixie (1912) spun tales of the “friendly relation that existed between master and slave,” a visit to the auction block in New Orleans was a painful memory. “The slave market I did not like,” she wrote. “That was really the only objectionable thing about slavery, the being bought and sold.” Another enslaver, Letitia Burwell of Virginia, rhapsodized in her 1895 memoir over the “mutual affection existing between the white and black races” in the South. But the “class of men in our State who made a business of buying negroes to sell again farther south” were a breed apart: “These we never met, and held in horror.”

Nearly half a million Africans were brought to North America in the two centuries before Congress abolished the external slave trade in 1808. Over the next fifty years, around twice that number of African-Americans were moved from the states of the upper South and the Atlantic seaboard to the expanding cotton belt, and the enslaved population of the United States nearly quadrupled. Any hope that the ban on the external trade might curb or reverse slavery’s spread was dashed by this internal trade, which allowed slavery to metastasize from Georgia to Texas. The historian Ira Berlin aptly termed this gigantic movement of people a “second Middle Passage,” and recent studies have revealed its terrible contours with fresh clarity. In the process, historians have presented convincing evidence for slavery’s deep entanglement with the development of American capitalism.

During the boom years of the internal slave trade, from the 1810s to the 1850s, the buying and selling of human beings became essential to the exploitation of the southern interior. As the federal government removed tens of thousands of Indigenous people from the lower South, sugar and especially cotton became suddenly and astonishingly lucrative. To secure this windfall, enslavers living in the upper South and along the seaboard moved south and west, forcing their slaves to accompany them. But only around a third of the Black people who endured the second Middle Passage traveled alongside their existing enslavers. The other two thirds—more than 600,000 people—were bought and sold at the slave pens and auction blocks that Mary Norcott Bryan found so distasteful. The external trade had been replaced by a vicious commodification of human beings that was both novel and horribly familiar.

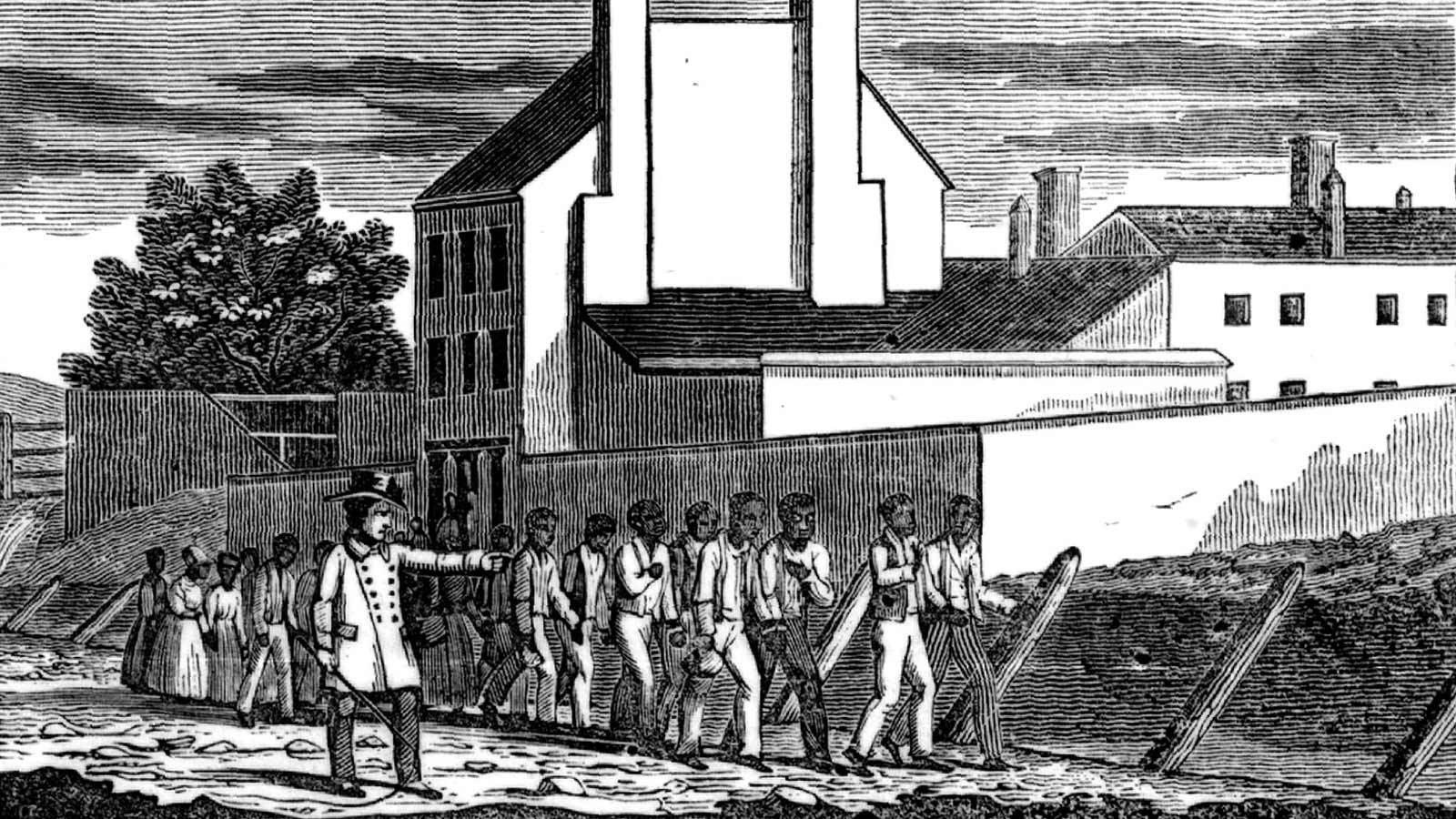

Joshua Rothman’s powerful new book, The Ledger and the Chain, excavates the “routine brutalities” of the internal slave trade by focusing on a single firm, Franklin & Armfield. Established in 1828 by Isaac Franklin of Tennessee and John Armfield of North Carolina, Franklin & Armfield connected enslavers in the upper South looking to sell with enslavers in the lower South looking to profit from the boom in cotton and sugar. Franklin & Armfield was not the first business to prosper from trading human beings, but it became the most successful slave-trading enterprise in antebellum America. With offices in Virginia, Louisiana, and Mississippi, the firm rose to prominence in the early 1830s alongside the lower South’s plantation complex.

Source: NYREV

Featured image: ‘Franklin & Armfield’s Slave Prison’; detail from an 1836 antislavery broadside depicting the offices of the slave-trading firm Franklin & Armfield in Alexandria, Virginia (Library of Congress)