Tamara Lanier is suing Harvard University for ownership of daguerreotypes of slaves who she says are her ancestors. Credit: Karsten Moran for The New York Times

By Anemona Hartocollis, The New York Times —

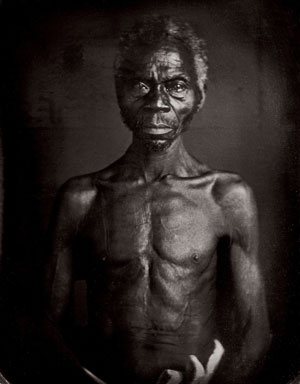

NORWICH, Conn. — The two slaves, a father and daughter, were stripped to the waist and positioned for frontal and side views. Then, like subjects in contemporary mug shots, their pictures were taken, as part of a racist study arguing that black people were an inferior race.

Almost 170 years later, they are at the center of a dispute over who should own the fruits of American slavery.

The images of the father and daughter, identified by their first names, Renty and Delia, were commissioned by a professor at Harvard and are now stored in a museum on campus as precious cultural artifacts.

But to the Lanier family, they are records of a personal family history. “These were our bedtime stories,” Shonrael Lanier said.

On Wednesday, Ms. Lanier’s mother, Tamara, 54, filed a lawsuit in Massachusetts saying that she is a direct descendant of Renty and Delia, and that the valuable photographs are rightfully hers. The case renews focus on the role that the country’s oldest universities played in slavery, and comes amid a growing debate over whether the descendants of enslaved people are entitled to reparations — and what those reparations might look like.

“It is unprecedented in terms of legal theory and reclaiming property that was wrongfully taken,” Benjamin Crump, one of Ms. Lanier’s lawyers, said. “Renty’s descendants may be the first descendants of slave ancestors to be able to get their property rights.”

Jonathan Swain, a spokesman for Harvard, declined to comment on the lawsuit.

Universities in recent years have acknowledged and expressed contrition for their ties to slavery. Harvard Law School abandoned an 80-year-old shield based on the crest of a slaveholding family that helped endow the institution. Georgetown University decided to give an advantage in admissions to descendants of enslaved people who were sold to fund the school.

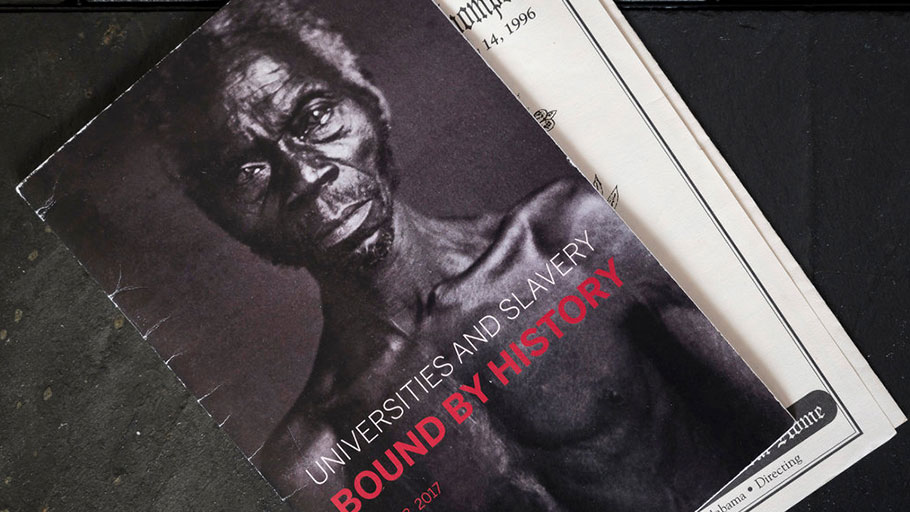

A program for a 2017 conference at Harvard on the links between academia and slavery. The program bears the image of Renty, a slave from whom Ms. Lanier says she descended. Credit: Karsten Moran for The New York Times

A series of federal laws has also compelled museums to repatriate human remains and sacred objects to Native American tribes.

The lawsuit says the images are the “spoils of theft,” because as slaves Renty and Delia were unable to give consent. It says that the university is illegally profiting from the images by using them for “advertising and commercial purposes,” such as by using Renty’s image on the cover of a $40 anthropology book. And it argues that by holding on to the images, Harvard has perpetuated the hallmarks of slavery that prevented African-Americans from holding, conveying or inheriting personal property.

“I keep thinking, tongue in cheek a little bit, this has been 169 years a slave, and Harvard still won’t free Papa Renty,” said Mr. Crump, who in 2012 represented the family of Trayvon Martin, an unarmed black teenager killed by a community watch member in Florida. Ms. Lanier is also represented by Josh Koskoff, a lawyer who represents families of the Sandy Hook elementary school massacre victims.

Renty and Delia were among seven slaves who appeared in 15 images made using the daguerreotype process, an early form of photography imprinted on silvered copper plates.

The pictures are haunting and voyeuristic, with the subjects staring at the camera with detached expressions.

The daguerreotypes were commissioned by Louis Agassiz, a Swiss-born zoologist and Harvard professor who is sometimes called the father of American natural science. They were taken in 1850 by J.T. Zealy, in a studio in Columbia, S.C.

Agassiz, a rival of Charles Darwin, subscribed to polygenesis, the theory that black and white people descended from different origins. The theory, later discredited, was used to promote the racist idea that black people were inferior to whites. Agassiz viewed the slaves as anatomical specimens to document his beliefs, according to historical sources.

The daguerreotypes were forgotten until they were discovered in an unused storage cabinet in the attic of Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology in 1976. They were thought to be the earliest known photographs of American slaves.

Notes found with the images give small clues as to the identity of the slaves — their names, plantations and tribes. Renty was born in Congo, according to the label on his daguerreotype.

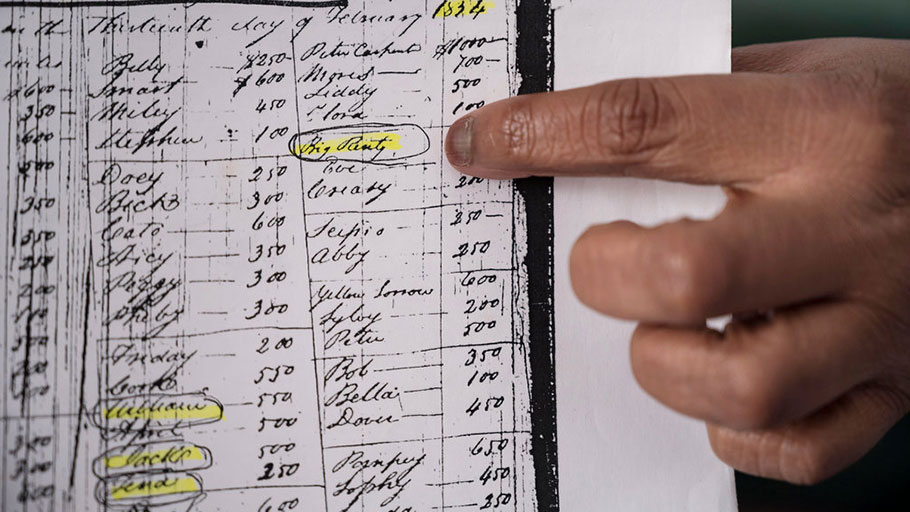

An inventory from 1834 listing the slaves on the plantation of Col. Thomas Taylor in Columbia, S.C. The names Big Renty and Renty appear on the list. Credit: Karsten Moran for The New York Times

In 2017, Ms. Lanier and her daughter attended a conference at Harvard on the links between academia and slavery that included speakers such as Drew Faust, Harvard’s president at the time, and the writer Ta-Nehisi Coates. They said they were offended to see the speakers positioned under a huge projection of Renty’s face.

Mr. Coates, the author of a widely discussed article making the case for reparations, said in an interview that while he deeply respected the scholars at the conference, he sympathized with Ms. Lanier’s cause.

“That photograph is like a hostage photograph,” Mr. Coates said of Renty’s image. “This is an enslaved black man with no choice being forced to participate in white supremacist propaganda — that’s what that photograph was taken for.”

He said he understood how Ms. Lanier felt seeing it at the conference. “I get why it would bother her,” he said. “I wasn’t aware of all that at the time.”

Interviewed at her home in Norwich, Ms. Lanier, a retired chief probation officer for the State of Connecticut, said she had not heard of the photos until about 2010, when she began tracing her genealogy for a family project.

Her mother, Mattye Pearl Thompson-Lanier, who died that year, had passed down a strong oral tradition of their family’s lineage from an African ancestor called “Papa Renty.” Shonrael, Ms. Lanier’s daughter, wrote a fifth-grade project about her ancestor in 1996.

The lawsuit could hinge on evidence of that chain of ancestry. Ms. Lanier’s amateur sleuthing led to death records, census records and a handwritten inventory from 1834 of the slaves on the plantation of Col. Thomas Taylor in Columbia and their dollar values.

The slave inventory lists a Big Renty and a Renty, and listed under the latter is Delia. Ms. Lanier believes that Big Renty is her “Papa Renty” and the father of Renty and Delia, and has traced them to her mother, who was born to sharecroppers in Montgomery, Ala.

Her genealogical research has its skeptics. Gregg Hecimovich, who is contributing to a book about the slave daguerreotypes, to be published by the Peabody next year, said it was important to note that the slave inventory has the heading “To Wit, in Families.” Big Renty and Renty are at the top of separate groupings, he said, implying that they are the heads of separate families.

The image of Renty was one of several daguerreotypes commissioned by Louis Agassiz, a Harvard professor who believed that black people and white people descended from different origins. Credit: J.T. Zealy, via the Peabody Museum, Harvard University

“I’d be very excited to work with Tamara,” said Dr. Hecimovich, who is chairman of the English department at Furman University. “But the bigger issue is it would be very hard to make a slam-dunk case that she believes she has.”

Molly Rogers, the author of a previous book about the images called “Delia’s Tears,” said that tracing families under slavery was extremely complex. “It’s not necessarily by blood,” she said. “It could be people who take responsibility for each other. Terms, names, family relationships are very much complicated by the fact of slavery.”

One intellectual property lawyer, Rick Kurnit, said he thought Ms. Lanier would have a hard time claiming ownership of the daguerreotypes. He said the famous photograph “V-J Day in Times Square,” for instance, belonged to the photographer and not to the sailor or the nurse who are kissing. But that image, of course, was taken in a public space.

Yxta Maya Murray, a professor at Loyola Law School, Los Angeles, said that images taken by force were tantamount to robbery. “If she’s a descendant, then I would stand for her,” Professor Murray said of Ms. Lanier.

One argument for keeping the daguerreotypes in a museum is that they are fragile physical objects, which degrade when exposed to light, said Robin Bernstein, a professor of cultural history at Harvard who has studied them.

She declined to take a position in the legal dispute, but said that the images were safe at the Peabody. “Frankly, there are other repositories to keep them safe,” she said. “What I do know is that no ordinary individual such as myself could keep them safe in a home.”

The question remains what Ms. Lanier would do with the images of Renty and Delia if she were to win her case in court.

Ms. Lanier, who is asking for a jury trial and unspecified punitive and emotional damages, says she does not know, and would have to have a family meeting about it. She does not rule out licensing the images.

Mr. Crump, her lawyer, had another idea. The daguerreotypes, he said, should be taken on a tour of America, so that everyone can see them.