Dorothy Brown has spent her career as a law professor documenting racism in a tax system that’s supposedly colorblind.

Growing up in the Bronx during the 1960s and ’70s, Dorothy Brown couldn’t escape racism. It was all around. Her father, James, a plumber, being barred from joining the local union. Her mother, Dottie, having to battle prejudiced teachers, including one who marked down Dorothy’s sister’s grades so the precocious child wouldn’t upstage her White classmates. Or the White cop beating a handcuffed Black man in the backseat of a cruiser, something she once observed while waiting to cross a street.

As a teenager, Brown thought she’d found a way out—a loophole in American racism. Taking an accounting class, the self-described math geek discovered the U.S. tax code, a universe governed by intricate rules where race wouldn’t matter. In tax law, she thought, “the only color that mattered was green.” The assumption carried her through an early career as a tax attorney, an investment banker, and then a political appointee in President George H.W. Bush’s administration.

After that, though, Brown spent a quarter century trying to prove the opposite: that although tax laws may appear to be colorblind, they still discriminate against Black Americans. Now the Asa Griggs Candler professor of law at Emory University, Brown is preparing to publish a book that’s the culmination of years of research, titled The Whiteness of Wealth: How the Tax System Impoverishes Black Americans—and How We Can Fix It.

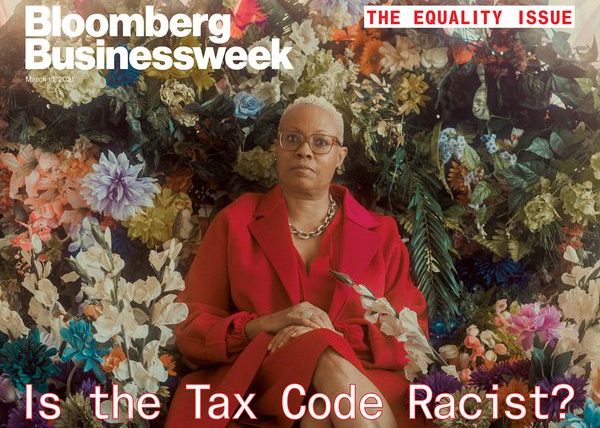

Featured in Bloomberg Businessweek, March 15, 2021. Subscribe now. PHOTOGRAPHER: BRAYLEN DION FOR BLOOMBERG BUSINESSWEEK

It arrives at an opportune time. After decades during which the 61-year-old Brown says mainstream tax and policy experts “either dismissed, attacked, or ignored” her, her ideas appear to be finding an audience. “People are starting to pay more attention to her work and what she’s been telling us for a while,” says Chye-Ching Huang, executive director of New York University’s Tax Law Center.

Last summer, after the killing of George Floyd ignited protests around the country, Brown got more calls from reporters than she’d received in her entire career. By the time President Biden promised, on his first day in office, to identify and dismantle systemic racism perpetuated by all federal departments, staffers on Capitol Hill were already consulting Brown about the Internal Revenue Service’s impact on racial disparities. “Suddenly people wanted to talk about race and tax,” she says.

With The Whiteness of Wealth, Brown has turned a notoriously boring topic into a surprisingly accessible and lively 288-page book, relying on examples from real families, including her own, to guide readers through the intricacies of a tax code provisioned for just about every milestone in a person’s life—education, marriage, homeownership, childbearing, death and inheritance. Generations of lawmakers have optimized the system for White people, she argues, with the result that in the U.S.’s supposedly progressive and race-neutral tax code, Black people end up paying more than White people with the same incomes.

The challenge for Brown’s research has been all the greater because the IRS doesn’t take race into account when it analyzes its giant trove of tax data. So she had to laboriously stitch together information from dozens of other sources to prove her book’s thesis. The best evidence that the system is unfair to Black people is the sheer size and persistence of the racial wealth gap. The median White family has a net worth eight times the typical Black family’s wealth. According to Federal Reserve figures, that’s the same size gap as in 1983, despite higher incomes, educational gains, and extraordinary progress by individual Black people, including to the highest office in the land.

The book also serves as something of a primer on how wealth works in America, showing how the rich pass assets to their children and why those starting from the bottom face such a difficult climb. Brown devotes her final chapter to advice for Black readers trying to navigate a system that disadvantages them at every turn. “Black Americans need to be defensive players,” she writes, “choosing strategies in their educations, careers, and family lives that compensate for oppressive practices and policies.” She also pushes for major tax changes to erase biases toward Whites and to assist all people, especially Black ones, who are trying to build wealth. Never again should politicians discuss tax reform without considering race, she says. “I literally want to change how America talks about tax policy.”

One afternoon in the early ’90s, Brown pulled out an essay she’d been looking forward to reading by her friend and mentor Jerome Culp, the first professor of color to receive tenure at Duke University’s law school. She’d been feeling isolated at her first academic job, with White colleagues who she says seemed clueless about race, at best. And here was Culp arguing that race should no longer be overlooked in important areas of the law. “There may be an income tax problem that would benefit from being viewed in a Black perspective,” he wrote by way of example, “but until you look, how will anyone know?” Brown called Culp and promised to try.

It took several years for her to publish her first research on the question, focusing on the taxation of married couples. Black Americans are more likely to be single, and if they’re married, it’s more likely both spouses will be working. These considerations wouldn’t have mattered when the income tax made its debut in 1913, because all earners were treated the same regardless of marital status. But in 1930 a rich White shipbuilder named Henry Seaborn persuaded the U.S. Supreme Court to lower his tax bill by imputing half his income to his wife. Congress eventually went along, and ever since, couples with only one high earner have paid less. Brown realized this policy had meant higher tax bills for her parents: The tax code essentially treats a plumber and a nurse who are paying for child care and commuting expenses with after-tax dollars the same or worse than it does a banker earning their combined salaries whose spouse stays home with the kids.

In the next 20 years, Brown went on to systematically catalog other ways in which, when Black families like her own tried to hoist themselves up the economic scale, the U.S. tax system pulled them down. Her colleagues, who were overwhelmingly White, expressed skepticism, however. “Dorothy, everybody knows your work is irrelevant, because Black people are poor and don’t pay taxes,” she says one professor told her, rudely laying bare an assumption she’s confronted countless times. (Four-fifths of Black households don’t fall below the poverty line.)

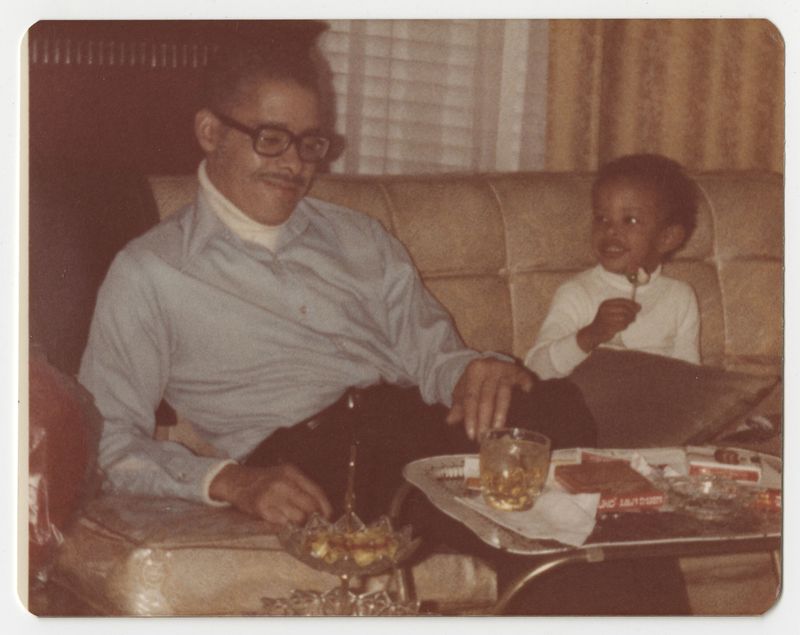

Brown’s father, James, with her nephew Jamaal in the early ’80s.SOURCE: DOTTIE BROWN

Brown’s early published work “caused her lots of professional grief,” recalls her friend Mechele Dickerson, a law professor at the University of Texas at Austin. “People thought you were just trying to be controversial—that you’re just making stuff up.” Those on the left asked if this was about class, not race. Conservatives posed a different question: Wouldn’t these disparities disappear if Black taxpayers just acted more like White ones?

Brown’s answer to both is that your class may change but your race can’t, no matter how differently you behave. “Blacks graduate from college with more debt, do not get jobs as easily as Whites, are not paid the same wages as their equally qualified White peers, are steered toward lower paying jobs, and have an unemployment rate twice that of Whites—yet are more likely to provide financial support for extended family,” she writes in her forthcoming book.

These present-day disparities are piled on top of a shameful history of Black Americans being purposely excluded from landmark federal legislation and programs. “For Whites, there were government interventions that created a middle class,” says New School economics professor Darrick Hamilton, an adviser to Senator Bernie Sanders’s 2020 presidential campaign who considers Brown a mentor. He points to the Homestead Act in the 19th century and much of the New Deal and the GI Bill in the 20th. “When Blacks were able to amass pockets of wealth, it’s been vulnerable to confiscation, theft, and terror,” he adds, citing the devastation wrought in Black neighborhoods by predatory subprime lenders as an example.

Brown before her high school graduation in 1976.SOURCE: DOTTIE BROWN

Brown argues that “tax policy adds insult to injury” by magnifying the financial toll of Blackness. The tax treatment of housing is a textbook case. Interest paid on mortgages is deductible, but there’s no comparable perk for renters, who are disproportionately Black. Also, White homeowners tend to pocket gains upon resale, which are largely tax-free. In contrast, Black homeowners are very likely to lose money on their investment, because homes don’t usually appreciate much in diverse neighborhoods that are shunned by White buyers. And losses aren’t tax-deductible.

Or consider tax incentives the federal government offers on 401(k)s and other types of retirement savings plans, which add up to more than a quarter trillion dollars per year, according to the Tax Policy Center. Only about half of U.S. workers have a retirement account, and they’re disproportionately White. Meanwhile, Black people are far more likely to have jobs that fail to provide 401(k)s and other corporate benefits, such as health care and flexible spending accounts, that are heavily subsidized by the tax code.

These discrepancies are nothing new—Brown’s father, locked out of the plumbing union for the first 20 years of his career, was employed by a small private company that offered no retirement or health-care plan. Now, though, the gap between different classes of workers might be widening, with the rise of the gig economy and corporations outsourcing more work to contractors. Brown is wary of the trend, seeing it as a “new form of occupational segregation” that’s ensnaring a disproportionate number of Black workers.

Other factors prevent Black Americans from saving and taking full advantage of perks in the tax code, too. White parents send checks to their children for college tuition or the down payment for their first home. Money in Black families tends to move in the other direction, meaning successful Black professionals are far more likely to support parents or other family members.

Problems such as these are so pervasive and stubborn that they’re invulnerable to “magic bullets” proposed by both the Left and the Right, Brown says. Policies geared toward boosting Black homeownership, for example, could channel even more Black savings into investments that ultimately prove unprofitable. Education, so often floated as the key to economic advancement, can indeed boost earnings, but it also often saddles graduates with debt. (According to Federal Reserve data from 2019, 30% of Black, non-Hispanic households had student loans, compared with 20% for White, non-Hispanic households.) Here, too, tax policy adds insult to injury. While homeowners can usually deduct all their mortgage interest, student-loan holders can only deduct $2,500—or zero if their income exceeds $85,000 a year.

Brown is often asked: Does all this mean the writers of these tax laws were racist? “The question of intent is really irrelevant,” she says. “It’s hurting Black Americans whether Congress meant to or not.”

For all that Brown knows of racism, the lived and the learned, she can still find herself shocked by the damage it inflicts.

One summer afternoon in 2018, she was in her three-bedroom “dream house” on Martha’s Vineyard, the island getaway for many Black professionals and celebrities. She was working toward her other dream, the book about the tax code she’d been contemplating for a decade, when she came across a startling statistic. Sixty percent of Black Americans who start college never finish it. After seeing the number, she shut her laptop, went to the beach, and stared at the ocean for a couple hours. Something about all those dreams denied and the contrast with her own experience hit her hard. “This is more messed up than even I knew—and I can’t take it,” she thought. She almost gave up the project.

When Brown was growing up, racism was a constant. Given how banks treated Black buyers, purchasing a home would have been impossible for her family if her father hadn’t gotten help from his White boss. And the children’s educational advancement might have been thwarted had James and Dottie, repeatedly blocked on their own career paths, not been determined to give their two daughters a better future. For a while, Dorothy and her sister attended a racially diverse elementary school, where they excelled. But after Dottie learned from another parent that Dorothy’s sister wasn’t being graded fairly, she lied about their address and had them transferred to another school, where they found more supportive teachers.

“Something my mother taught us was, ‘You’re no better than anyone else, and no one else is better than you,’ ” Brown says. “I didn’t feel that racism would limit me. I knew I’d have to deal with it, but I didn’t think it was hopeless.” Still, she abandoned her original plan to be a civil rights attorney like her hero, Thurgood Marshall. She didn’t want racism to be the focus of her professional life, too. “It’s too personal, it’s too hurtful, it’s too painful to hear these stories. I have enough stories.”

A stroke of luck helped her avoid the student debt that burdens many other Black professionals. Her father, who was eventually hired as a union plumber by the New York City Housing Authority, briefly lost that job during the city’s mid-’70s fiscal crisis. The layoff helped Brown, who graduated high school at 16, qualify for a full scholarship to Fordham University, which she could attend while living at home. A law degree from Georgetown University, and a degree in tax law from NYU followed.

A federal clerkship led to a job at a boutique law firm that handled municipal bonds. Then in 1987 she was hired away by a client, the investment bank Drexel Burnham Lambert. The firm, famously cutthroat and aggressive, made huge profits on the junk bond boom, and it would later collapse in scandal after the conviction of executive Michael Milken. Brown recalls that a managing partner had this piece of advice: “Dorothy, if you want loyalty, buy a dog.”

Brown moved to Washington, D.C., in 1989 to work at the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development as a political appointee in the first Bush administration. From the 1988 presidential race, she’d concluded that neither party was good on race. She says she gravitated to the Republican Party because it called for shrinking the role of government, and she believed the government was “one of the more racist actors out there.” Her dalliance with the GOP carried on for years, before she switched parties to support Barack Obama’s election in 2008.

Brown’s first academic job was at George Mason University’s right-leaning law school, now named for the late Supreme Court justice Antonin Scalia. Working on predominantly White campuses, Brown says she has dealt with disparaging comments from faculty, disrespectful students, and other instances where she felt treated differently because of her race. In 2001, when she was up for a job at Washington and Lee University, a Virginia institution named for a Confederate general, she presented her work and was interrupted so many times that faculty members later apologized for their colleagues’ rudeness. “Dorothy, you were mugged, but you managed to hang onto your purse,” said one friend who was there.

In past jobs, Brown says, the profit motive—the fact that she could help close a deal or untangle a tax quandary—had seemed to moderate her co-workers’ racial biases. Academia felt different, but she couldn’t always be sure when the friction had something to do with her race—and, if it did, when to say something and when to bite her tongue. Brown calls this “racism triage”—where “you reserve your energies only for the worst” incidents. To cope, she relied on a small network of Black women law professors at other schools, whom she’d call, asking, “Is this me? Or is this messed up?”

When incidents occurred, Brown pushed back using the political and strategic savvy she’d learned in earlier jobs. It would take two rounds of voting by the Washington and Lee faculty, but she eventually got the job there, and she thrived. Those opposed to her “outed themselves early on,” she says. “I didn’t ever have to worry about them again.”

In 2007, Brown jumped to Emory University in Atlanta, a more prestigious school that also had a complicated history on race. Tenure protection allowed her to push forcefully for more diversity in the law school. “I’m always ‘the woman from the South Bronx,’ ” she says. “I am very direct. I don’t put up with a lot. I don’t really care if you don’t like the tone.”

In 2013, Brown was recruited for a powerful job in Emory’s administration, and, though reluctant to give up her research and teaching, she served for three stressful years. In the wake of protests from students demanding, among other things, more faculty of color, she ran a fund to hire diverse faculty and set up initiatives to mentor them. Colleagues say they recognize that Brown’s outspokenness can be balanced by a measured approach to important and difficult work. “She may seem impatient, but she also believes in taking it one step at a time,” says Claire Sterk, who recently stepped down as Emory’s president. By the end, “she can make an argument that becomes very hard for people to not accept.”

Biden’s election could allow Brown to take her research to a new level. Just hours after being sworn in on Jan. 20, the president signed an executive order creating a cross-agency group with a mandate to address systemic racism in the U.S. government. Their duties will include gathering data to track the effects of policies on disadvantaged groups. “There’s no reason this should remain in the Dark Ages,” says Brown. Strict rules should be put in place to make sure the data isn’t misused, she adds. She’s also clear, to that end, that she isn’t advocating for the IRS to add a race check box to the 1040 form. There are workarounds, such as using surveys and matching anonymized data sets.

“I literally want to change how America talks about tax policy,” Brown says.PHOTOGRAPHER: BRAYLEN DION FOR BLOOMBERG BUSINESSWEEK

With the right data and the right priorities, says Brown, the U.S. could do a better job of using its tax code to help close the racial wealth gap. Other policymakers are thinking along the same lines. “You’ve got this tool that is potentially powerful for reducing inequality, including racial disparities,” says NYU’s Huang. “One of the questions she’s asking is: Why isn’t it doing more?”

Brown’s own reform plan would strip the tax code of exemptions and deductions that steer advantages to White Americans. All income should be taxable, she says. No more exclusions for gifts, inheritances, or property sales. Proceeds from investments should be taxed at the same rate as wage income, and marital status shouldn’t affect taxes. There’s only one deduction that she would add to the code: a “living allowance deduction” that would prevent or cut taxes on low earners. By requiring everyone else to pay progressive tax rates on all their sources of income, the U.S. could afford to lower rates and get the same revenue.

The Supreme Court would probably strike down any race-based tax credit introduced as a form of reparation to descendants of slaves, says Brown. So her next-best choice is an annual tax credit for taxpayers whose wealth is below the U.S. median. The credit would help all poorer Americans trying to build wealth in a country where it’s gotten more difficult to move up the economic ladder on earnings from work alone. But because the typical Black family has a net worth of $24,000, compared to a median wealth of $122,000 for all Americans, it would disproportionately aid Black Americans.

None of Brown’s favored remedies look likely to become law in a Congress where Democrats barely have a majority. But after watching attitudes toward racial justice shift last year, she’s optimistic. “We are well positioned to start making the kinds of demands that the wealthiest White Americans have made for decades,” she says.

In the meantime, Brown’s new book has plenty of practical pointers for Black Americans: Take advantage of a 401(k) if you have one. If you’d rather buy a home in a diverse neighborhood—which is understandable—try not to sink your entire nest egg into that purchase. Investing in stocks is likely to provide a better return, despite a “racist financial system that hasn’t seen Black Americans as potential customers.”

Finally, don’t despair or blame yourself for failing to get further along financially. “The reality of how ordinary White Americans build wealth is hidden,” leaving “Black families bewildered about their inability to achieve the financial security of their White peers,” she writes. White wealth snowballs over a lifetime: A tuition payment by Dad, a job at the family business, a small inheritance from Grandma, and soon even apparently middle-class young adults have amassed enough that they’re able to return the favor to their children as they age. This system has been humming along for centuries. As Brown puts it, “Whiteness itself, and the legacy of advantages that comes with it, is the magnet that attracts wealth.”

Source: BLOOMBERG