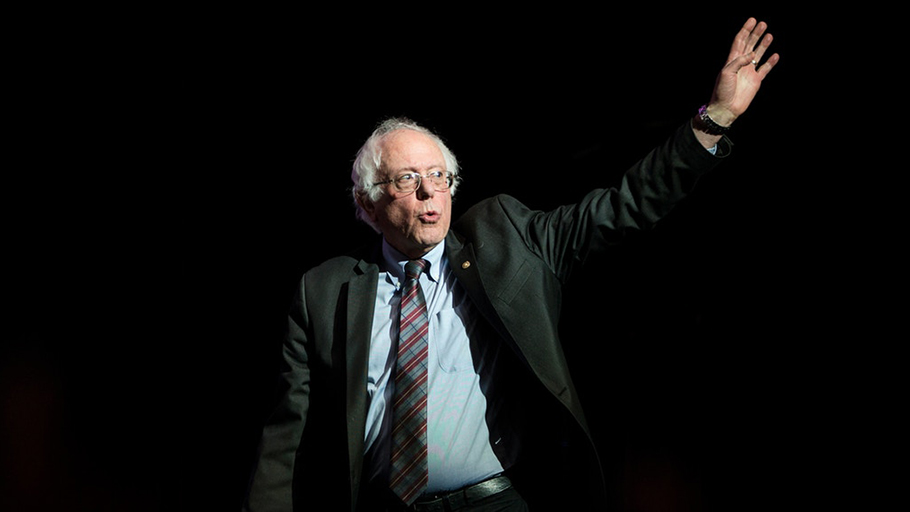

Sen. Bernie Sanders waves as he takes the stage at the Our Revolution Massachusetts Rally in Boston, Mass., on March 31, 2017. Photo: Scott Eisen/Getty Images

By Briahna Gray, The Intercept —

AFTER SENS. KAMALA HARRIS and Cory Booker were asked about reparations for slavery in a Breakfast Club interview last week, the issue quickly became hot on the 2020 campaign trail, with candidates Elizabeth Warren and Julián Castro quickly voicing their support for the policy. Last night, the reparations question surfaced again when Sen. Bernie Sanders was asked for his position during a CNN Town Hall hosted by Wolf Blitzer.

“There are massive disparities that must be addressed,” Sanders answered. “There is legislation that I like introduced by Congressman Jim Clyburn — it’s called the 10/20/30 legislation — which focuses federal resources in a very significant way on distressed communities.”

He went on: “I think we have to do everything that we can to end institutional racism in this country. It is not acceptable to me that the rate of childhood poverty among the African-American community is over 30 percent in this country — that is beyond belief — that African-Americans die from cancer at higher rates than whites. So we’re going to do everything we can to put resources into distressed communities and improve lives for those people who have been hurt by the legacy of slavery.”

Sanders’s response was broadly similar to the other candidates who support reparations. Unlike in 2016, when Sanders joined Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama in not supporting reparations, the Vermont senator was careful not to appear dismissive of the underlying right to recompense. Like Sens. Cory Booker, Harris, and Warren, he acknowledged racial disparities resulting from “the legacy of slavery” and the need to address them. Unlike any other 2020 candidate, he went on to offer his support for specific legislation, which would address racial disparities: the Clyburn/Booker 10/20/30 aimed at attacking persistent poverty.

Blitzer posed a follow-up question demanding an up-or-down answer: “So what is your position specifically on reparations?”

At this point, Sanders asked a crucial, as yet unasked question: “What does that mean? What do they mean? I don’t think anyone’s been very clear.”

And he’s right.

Up until now, no one’s bothered to define reparations in the context of 2020 vetting. And the discourse has suffered for it.

Up until now, no one’s bothered to define reparations in the context of 2020 vetting. And the discourse has suffered for it.

Like Harris and Booker before them, Warren and Castro’s support for reparations amounts to a support for a principle, but not a policy.

“Black families have had a much steeper hill to climb, we need systematic structural changes to address that,” Warren has said.

Castro, the former secretary of Housing and Urban Development, offered: “I have long thought that this country would be better off if we did find a way to do that — reparations.”

The “structural changes” Warren evokes aren’t necessarily racially specific. And Castro’s statement that we’d be “better off” with reparations manages to dodge the question of whether he supports reparations as a political matter entirely. “This is not something that I see through a political lens,” he said, before proposing a “task force” to look into the issue.

Although Harris has said she supports “some kind of reparations,” the examples she’s pointed to, like her LIFT tax cuts, aren’t race-specific, though they would disproportionately help black Americans. Booker has similarly hasn’t proposed race-targeted programs, pointing instead to his baby bonds plan, criminal justice reform, and other anti-poverty programs.

Because they’ve not been pressed for details, the candidates have been able to voice “support” for reparations without committing to any particular policy or goals. But while the press may not appreciate the difference between symbolic posturing and genuine policy commitments, many black Americans have.

“WHAT @KamalaHarris is proposing is a CLASS SPECIFIC piece of legislation,” tweeted Yvette Carnell, founder of the #ADOS movement, which advocates for the interests of American descendants of slavery. “Reparations for #ADOS is a RACE SPECIFIC piece of legislation. America inflicted race specific harm that requires race specific redress. Stop trying to lie to us. We’re not stupid.”

Carnell’s tweet followed an interview in which Grio reporter Natasha Alford asked Harris a critical follow-up question after the California senator evoked race-neutral programs like her LIFT Act in response to an inquiry about reparations: “So by default, it affects black families, but there’s not a particular policy for African-Americans that you’ve explored?”

Harris’s answer, after a lengthy preamble, was no: “I’m not going to sit here and say I’m going to do something that only benefits black people. No! Because whatever benefits black people will benefit society as a whole and the country, right?”

Harris couldn’t have been more clear about not supporting a race-specific reparations program. Yet the press has generally covered all of these answers on the question of reparations as yeses.

Astead Herndon at the New York Times has reported that Warren, Castro, and Harris “supported reparations,” though he acknowledged that Warren’s campaign ”declined to give further details on that backing.”

The no’s, too, have been described inconsistently. In the space of one article, Herndon characterized Sanders as having “dismissed” reparations as impractical in 2016, while writing that Clinton had merely “declined to support” reparations that year. It would be more accurate to say that she dodged answering the question directly.

And while neither Sanders, Clinton, nor Barack Obama answered yes on the question of reparations, Herndon characterized Obama’s response more gently, writing: “The first black president was seen in some political quarters as reticent about prioritizing the interests of black voters, and he called the idea of reparations impractical in 2016.”

It’s worth asking who benefits from this inconsistent coverage and empty political posturing.

CONSIDER THE EFFECT of Obama’s rationalization against reparations, which has gone largely unscrutinized.

In a 2016 interview with Ta-Nehisi Coates, Obama argued that “as a practical matter, it is hard to think of any society in human history in which a majority population has said that as a consequence of historic wrongs, we are now going to take a big chunk of the nation’s resources over a long period of time to make that right.”

Of course, that’s not true. As Obama went on to acknowledge, Jews received reparations from Germany following the Holocaust, and Japanese-Americans received reparations after internment during World War II. Obama attempted to distinguish black Americans from other groups, adopting the right-wing argument that reparations were politically impractical because too much time had passed for black Americans to collect on the debts of slavery. According to Obama, Holocaust survivors and their children — only one or two generations removed from the genocide — could say “that was my house. Those were my paintings. Those were my mother’s family jewels” in a way that black Americans could not.

But the passage of time has never been more than a pretext used to justify not paying what America had promised it would: the now proverbial 40 acres and a mule.

The passage of time has never been more than a pretext used to justify not paying what America had promised it would: the now proverbial 40 acres and a mule.

The question of reparations has been raised continuously since before the end of the Civil War — including by President Abraham Lincoln who seriously considered the issue — not for slaves, but for slaveholders who felt they should be compensated for their lost “property.” Indeed, an entire movement of slavery opponents pushed for years to simply buy out the slave population to avoid war. And throughout the 20th century — including in the 1960s, when those born into slavery were in their 90s, and many millions more of their immediate descendants still lived — requests for reparations were continually ignored. Over the years, the excuse that “too much time has passed” increasingly came to be rooted in reality. But only because it was a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Obama, a lawyer, should know better than to argue that the statute of limitations on reparations had lapsed when a timely claim had been made. But in truth, there are now legitimate (but not insurmountable) logistical concerns to administering a race-specific plan. How do you account for people who are only partially descended from American slaves? What about those who can’t prove their lineage? What about families who immigrated early enough to experience Jim Crow, but after slavery? Is the most politically viable way to deliver material benefits to black Americans via intersectionally designed universal programs?

These questions are crucial to anyone serious about pursuing reparations. And, it could be argued, they’re the questions that a genuine supporter of reparations wants to explore. But none of them were ever put to Obama, Clinton, or Sanders in 2016. The assumptions put forward by Obama and others were never challenged. And none of these foundational questions were raised at last night’s town hall. It’s almost as if the interest in reparations was only symbolic. Or political.

By asking Blitzer to define what reparations actually means, Sanders shifted the conversation from speculative rhetoric to practical policy.

As I argued last week, the void left by a lack of serious political conversations about reparations has created opportunities for politicians to use reparations as political brinkmanship, a way to effect commitment to black Americans without committing to anything beyond lip service.

But by asking Blitzer to define what reparations actually means, Sanders shifted the conversation from speculative rhetoric to practical policy and in doing so, made it more likely that the goals of reparations will be pursued in good faith. He forced everyone to show their hand.

IMPORTANTLY, THERE IS currently no consensus on what reparations would look like. Coates famously wrote over 15,000 words making a powerful case for reparations, but even he failed to come to a firm conclusion about what we should do next.

When I spoke to Duke University professor Sandy Darity last week, an authority on the subject of reparations, he emphasized that a full-scale attack on the racial wealth gap will require a racially targeted project on the order of a large-scale reparations program. But he also acknowledged that universal programs of the type now on the table can reduce racial wealth inequality.

Darity has specifically championed Booker’s baby bonds program as the class-based plan best positioned to close the racial wealth gap. But he was also clear that the program is flawed insofar as it’s pegged to parental income — not wealth, where the biggest racial disparity lies. (The original baby bonds program he designed with Ohio State economist Darrick Hamilton was keyed to wealth. But Darity says that Booker chose to base his plan on income because of “convenience.” When I pointed out that millions of parents calculate their wealth to apply for federal student aid for their college-bound kids every year, Darity agreed that it wasn’t as easy, but it was doable).

The point is that universal programs are not a substitute for racially targeted interventions. But “the ideal world,” he says, is one in which you’d combine approaches that target wealth: prioritize giving more resources to the poor while also closing the gap by taxing the rich.

To ensure that the ostensible goals of black Americans are met, it’s important not to lose sight of the fact that equality will require a multipronged approach.

ALL THE 2020 candidates can be faulted for not turning attention to the question of reparations until campaign season. But it feels strange to demand that candidates throw their unqualified support behind something that no one can yet define.

The preliminary questions journalists should ask instead of “do you support reparations?” are these: 1) Will you commit to meaningfully researching and developing a plan for reparations, and 2) If and when you develop a policy, will you commit to implementing it?

I suspect most candidates would have a much easier time answering “yes” to this formulation, and rightly so. At this point, every candidate who has opined has done a solid job of articulating the why of reparations: slavery, Jim Crow, disparities. Now the question worth asking is the how.

Ironically, as long as the question of reparations remains vague, it’s more likely to be controversial. Undefined, reparations can take the form of the public’s worst fears: a free “check” to the “undeserving” black masses (which, who knows, might be the best option), versus tuition or housing grants that mimic those New Deal programs from which blacks were historically excluded. Both black and white legislators have shied away from the question of reparations, treating it as a political hot potato — hiding behind the idea that reparations are just too complicated to administer. Nailing down an actual plan destroys that rationale. Vagueness is a gift to the non-committal.