Farmers say Beijing’s growing presence in Kenya is having a negative impact on their lives, culture, and ability to make ends meet.

EMBARINGO, Kenya — On a sticky morning on the slopes of Mount Kenya, Solomon Wambogo Munyua sprinkles water on the long and sturdy green shoots of the garlic crop he planted in January.

His farm is just one-eighth of an acre, perched on the humid mountainside in the fertile East African Rift Valley, over which glacier-capped peaks loom.

It isn’t an easy existence, and his concerns include issues ranging from transportation costs to the low prices paid for produce.

But these complaints are dwarfed by a new challenge farmers such as Munyua feel powerless to fight: imports of Chinese garlic flooding into the Kenyan market.

Munyua, 38, and other local farmers say they are being undercut by producers who ship garlic almost 7,000 miles by sea from the world’s most populous country. They accuse Beijing of “garlic dumping” and say they can’t compete.

“If you go the markets you will see that 80 percent of garlic is from China,” said James Kamau, who runs a support group for fellow farmers.

Munyua and Kamau, 40, are among those who say that China’s growing presence in Kenya is having a negative impact on their lives, culture, and ability to make ends meet.

But garlic is only a microcosm of the impact Chinese influence and investment are having across Africa.

Garlic is heaped on a mat beside a roadside stall in Kiawara, Kenya. Nichole Sobecki / for NBC News

The agriculture sector employs 40 percent of Kenya’s 49 million people and accounts for 26 percent of its economy.

In recent years, China has offered African countries loans, development aid and vast infrastructure projects as part of the Belt and Road Initiative, a $1.4 trillion network of modern trading routes.

Kenya now owes 72 percent of its bilateral debt — or around $5.3 billion — to China. That’s around one-fifth of Kenya’s total external debt.

With China holding the purse strings, it has the upper hand in any battle of wills — and garlic is just the latest foodstuff to be at the center of tensions here.

Eunice Ngima runs a small roadside stall selling garlic, onions, potatoes and other vegetables in Kiawara, Kenya. Nichole Sobecki / for NBC News

In October, Beijing’s ambassador to Kenya threatened a trade war after Chinese fish imports were halted amid claims the market was being flooded.

China also threatened to pull funding for the second phase of a railway line connecting Nairobi with the major Indian Ocean port of Mombasa. China financed and built the initial stage of the project at an estimated cost of $3.2 billion, making it Kenya’s most expensive infrastructure project since independence from Britain in 1963.

Around three months later, Kenya relented and scrapped the import ban on Chinese fish. It cited market forces.

‘Virgin land’

Most garlic farms in Nyeri County, the remote area where Munyua is based, are small-scale operations.

The location of his small plot of land makes it difficult to transport produce after it is harvested in May and November.

Munyua has to rent donkeys to carry the garlic along steep mountain cliffs and through forested valleys before reaching a mud road. Kiawara, the nearest town, is a 30-minute drive away from his farm and a further 4-hour journey from the capital, Nairobi.

Garlic farmer Solomon Wambogo Munyua in his field in Embaringo, Kenya. Nichole Sobecki / for NBC News

Munyua planted his garlic shoots in January, with the help of two workers he hires for the day at a cost of $3 each.

There’s ample water supply and rich volcanic soil here on what Munyua calls “virgin land.” His plot typically yields up to 600 pounds of garlic per season — earning him as much as $400, enough to send his son and daughter to school.

But he struggles to comprehend why many Kenyan consumers are opting for the rounder and smoother white Chinese garlic bulbs over locally grown produce. While Chinese garlic features larger cloves that are easier to peel by hand than the more intricate Kenyan variety, Munyua believes his country’s crop boasts a key advantage: its taste.

“Kenyan garlic is really sweet,” he said.

Garlic is also grown on an adjacent farm.

Cousins James Kariuki Wahome, 36, and Peter Munene Ndurui, 40, rent half an acre of land here.

Garlic farmer Peter Munene Ndururi rests in his field in Embaringo, Kenya. Nichole Sobecki / for NBC News

They live around 12 miles from the farm, so every morning they have to pay to jump on the back of a motorbike to get them here.

They arrive around 8 a.m. every day — except Sundays when they go to church — as any earlier in the morning is too cold to work on their plot of land. Whistling young men who sell lunch bags to farmers containing bread, milk and water drop by around 1 p.m., and the cousins continue to toil until around 5 p.m.

“Life is very hard,” Wahome said.

Wahome admits that he often struggles to support his five children due to the price of garlic fluctuating in the local market. The influx of Chinese produce hasn’t helped.

One-fourth of a world away

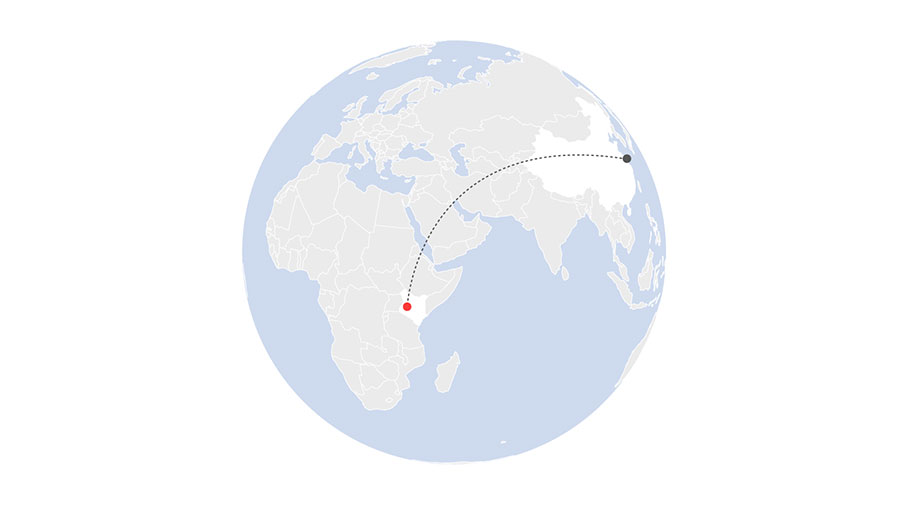

The 5,500-plus miles from Kenya to Shanghai is about the same distance as Los Angeles to New York City and back again.

Graphic: Robin Muccari / NBC News

One pound of garlic earns farmers around 36 cents “when it’s good,” but that figure can be a low as 23 cents at times, according to Wahome.

Munyua is among the farmers so worried about the imported bulbs that they want the government to take action, as it did with fish last year.

“Chinese garlic should be taxed high so that the Kenyan farmer can earn something,” Munyua said.

Corruption

Garlic is only part of the picture. Kenya exported $96.88 million in goods to China, but imported a total of $3.79 billion.

The Kenyan government’s horticultural crops directorate said supply and demand were among the factors when it comes to the availability of foreign garlic.

“As long as we don’t produce enough garlic, we may still continue buying garlic from China,” a spokesperson said, adding that the lack of sufficient farming knowledge and technology and limited machinery were also challenges in Kenya.

Kenya currently imports around 50 percent of its garlic, according to official statistics.

Fields of garlic in Embaringo, Kenya. Nichole Sobecki / for NBC News

While African governments have embraced China with open arms, Munyua questions whether the “win-win” notion that underpins the relationship is a reality.

“Is it beneficial for the common man?” he asked, claiming that one group benefits the most from China’s presence in Kenya. “The politicians.”

Transparency International ranks Kenya among the most corrupt countries in the world — 144th out of 180 nations on last year’s index.

Charles Gichuhi Ngari, a garlic farmer and village elder, was a child when the British battled Mau Mau rebels in the 1950s.

Charles Gichuhi Ngari sits with his wife, Esther Wairimu Gichuhi, and granddaughter Rose Wamboi Njoroge at their home in Embaringo, Kenya. Nichole Sobecki / for NBC News

The anti-colonial rebels used to hide from the British military not far from today’s garlic farms.

These lush green hills were known as “the white heights,” because they were full of white British settlers who took the best land.

“When black people heard, ‘this is not their land,’ they started fighting for it,” Ngari recounted.

He sees modern parallels.

“I have never gone to China, but China is a superpower,” Ngari said. “I just get up every morning to go to my farm … I see the news, ‘Kenya has borrowed this money from [China].’ I cannot tell you where the money goes.”

He highlighted the lack of local infrastructure that makes it so tough to compete with imports shipped from overseas.

“There is no road here,” Ngari said. “The money has been eaten.”

This report was funded by a grant from the Alicia Patterson Foundation.

Ismail Einashe is a journalist based in Nairobi, Kenya. He is an Alicia Patterson Foundation Fellow for 2019.