By M. Andrew Holowchak —

The two most significant issues that led to war between the North and South were, most scholars acknowledge, slavery and states’ rights. Northern states had fully abolished slavery by 1804, when New Jersey was the last Northern state to do so, and with an economy that did not depend on the labor of slaves, it demanded that the South do the same. Yet in demanding that the South follow suit, the North, Southerners maintained, was in contravention of the issue of states’ rights—that each state had the right to craft and implement its own laws and policies without Federal governmental intrusion. Yet while the two were independent issues in theory, in praxis they were not. That comes out in Southerner apologist George William Bagby’s somewhat mawkish essay, “The Old Virginia Gentleman”:

Fealty to the first great principle of our American form of government—the minimum of state interference and assistance in order to attain the maximum of individual development and endeavor—that was the Virginian’s conception of public spirit, and, if our system be right, it is the right conception.

Aye! but the Virginian made slavery the touchstone and the test in all things whatsoever, State or Federal. Truly he did, and why?

This button here upon my cuff is valueless, whether for use or for ornament, but you shall not tear it from me and spit in my face besides; no, not if it cost me my life. And if your time be passed in the attempt to take it, then my time and my every thought shall be spent in preventing such outrage.

According to Bagby, it was effrontery for Northerners to demand an end to slavery in the South. In making such a demand, the two issues became dependent. Southerners fought hard to keep their slaves only, or at least chiefly in Bagby’s view because they were told that they could not keep them.

That to which Bagby alludes has come to be called the Lost Cause—a sort of treacly revisit to the days before the Civil War, to a paradise moribund, never again to be revived. The Southern attitude is in some sense easy to understand. With up to 700 thousand men lost in the war on both sides—some 100 thousand more Union soldiers than Confederate soldiers and astonishingly nearly 25 percent of the soldiers on each side—Southerners do not have recourse to the sort of warrant available to Northerners: We won the sanguinary war, so that in itself is proof that God’s justice was on our side. Southerners, to justify the loss of some 260 thousand men, had to try to understand, from their perspective, why God slept while they fought.

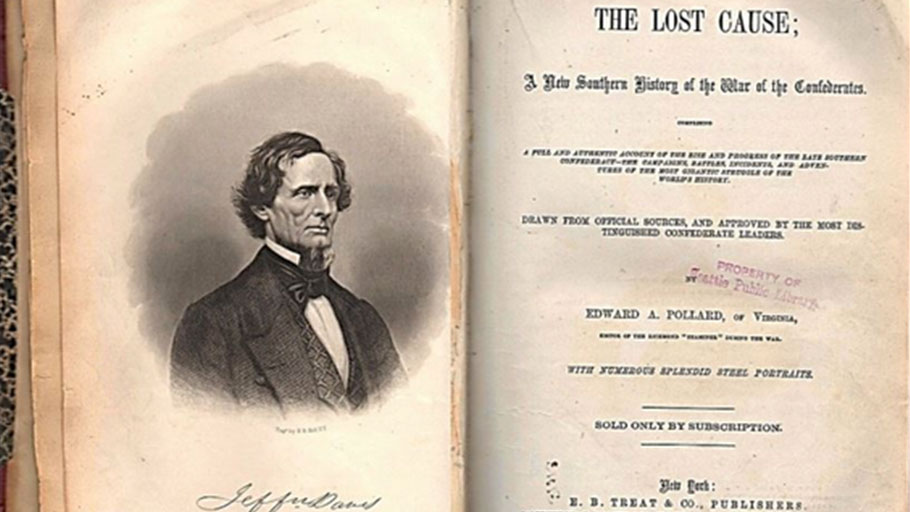

The term Lost Cause was first used by Edward A. Pollard in The Lost Cause: A New Southern History of the War of the Confederates published the year after the Civil War. Three Southern publications—Southern Historical Society Papers (1869), Southern Opinion (Richmond, 1867), and Confederate Veteran (1893)—entrenched the term and gave birth to a movement. The impassioned, lucid voice of Gen. Jubal “Old Jube” Early, the hero of the Battle of Lynchburg, who spent the final years of his life in Hill City after the Civil War, was prominent in Southern Historical Society Papers.

In 1866, Early wrote A Memoir of the Last Year of the War for Independence, in the Confederates States of America, in which he stated that he initially opposed secession of Southern states from the Union, but firmly changed his mind because of “the mad, wicked, and unconstitutional measures of the authorities at Washington, and the frenzied clamour of the people of the North for war upon their former brethren of the South.” Lincoln and his cronies were the real traitors of the Constitution. Recognizing the right of revolution against tyrannical government “as exercised by our fathers in 1776, … I entered the military service of my State, willingly, cheerfully, and zealously.”

The Civil War, Early unequivocally said in The Heritage of the South, was never about slavery from the perspective of the South. “During the war, slavery was used as a catch word to arouse the passions of a fanatical mob, and to some extent the prejudices of the civilized world were excited against us; but the war was not made on our part for slavery.”

Early argued that Southerners had long ago grasped that there was nothing objectionable, moral or otherwise, about the institution. Slavery was a natural state of affairs for Blacks, he stated, because of their biological inferiority.

The Almighty Creator of the Universe had stamped them, indelibly, with a different colour and an inferior physical and mental organization. He had not done this from mere caprice or whim, but for wise purposes. An amalgamation of the races was in contravention of His designs, or He would not have made them so different.

Blacks, added Early, in their state of subjugation were better off than they were in West Africa, where they wallowed in barbarism, sometimes to the extent of practicing cannibalism. In addition, said Early, black slaves on Southern plantations and in Southern cities were certainly better treated that the Blacks, and Whites, in Northern industrial sweatshops.

Early next turns to an oft-given objection to slavery: Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence. The argument asserts that slavery is wrong, because “all men are created equal.”

The assertion that “all men are created equal,” was no more enacted by that declaration as a settled principle than that other which defined George III to be “a tyrant and unfit to be the ruler of a free people.” The Declaration of Independence contained a number of undoubtedly correct principles and some abstract generalities uttered under the enthusiasm and excitement of a struggle for the right of self-government. … If it was intended to assert the absolute equality of all men, it was false in principle and in fact.

Observation, Early intimates, is sufficient to show the de facto falsity of the equality of Blacks and Whites.

Yet Jefferson did intend the equality of all men in his Declaration. In his original draft of the document, he castigates George III for keeping “open a market where MEN should be bought & sold.” The capitalization of men is Jefferson’s and it occurs to underscore the notion that Blacks qua men are deserving of the same fundamental rights of all other men. Moreover, Jefferson was a cautious, diligent writer who—his Summary View of the Rights of British America perhaps being an exception—was wont not to be moved by “enthusiasm and excitement.”

Jefferson did likely believe that Blacks were intellectually and imaginatively inferior to Whites. In Query XIV of Notes on the State of Virginia, he stated that Blacks, though very likely intellectually and imaginatively inferior to Whites, were morally equivalent to all other persons, and thus, they were undeserving of “a state of subordination.” That Isaac Newton was intellectually superior to all others of his day was not warrant for him having God-sanctioned rights that others did not have. God’s justice for Jefferson looks to the heart, not to the head. Early’s dismissal of Jefferson’s Declaration as containing an ineffective argument against slavery is harefooted, unpersuasive.

Old Jube then turns to what might be construed as a legal argument for slavery—an argument from precedence. There is constitutional sanction of slavery because there is constitutional sanction of states’ rights.

The Constitution of the United States left slavery in the states precisely where it was before, the only provision having any reference to it whatever being that which fixed the ratio of representation in the House of Representatives and direct taxation; that in reference to the foreign slave trade, and that guaranteeing the return of fugitive slaves. Had it been proposed to insert any provision giving Congress any power over the subject in the states, it would have been resisted, and the insertion of such provision would have insured that rejection of the Constitution. The government framed under this Constitution being one of delegated powers entirely, those powers were necessarily limited to the objects for which they were granted, but to prevent all misconception, the 9thand 10thamendments were adopted, the first providing that “The enumeration in the Constitution of certain rights shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people,” and the other that: “The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the states, are reserved to the states respectively, or to the people.

Early here claimed constitutional warrant for slavery being an issue subordinate to states’ rights. That is not necessarily to say that it was less of an axiological issue—as it may be the people on the whole feel more strongly about slavery, pro or con, than about states’ rights—but that the issue of slavery, whatever its worth, was to be decided by each state and not by the federal government. However Northerners, at least some of them, thought the issue was of such significance that it transcended states’ rights.

Here again we might profit in analysis by comparing Early’s view on constitutional warrant with Jefferson’s. Jefferson too worried mightily about the issue of states’ rights and slavery—the Missouri problem brought it into focus—and he too recognized that there was no constitutional warrant for eradication of the institution. Thus, he too maintained that the issue of slavery ought to be up to the individual states.

Yet Jefferson did not have the same regard for the sacrosanctity of the Constitution that Early did. For Jefferson, constitutions were living documents that needed overhaul with each generation, as each generation in the main advanced in knowledge and such advances needed to be instantiated.

Moreover, Jefferson, following other Enlightenment philosophers, certainly paved the path in his Declaration for a new way of looking at persons and fundamental rights: They were natural, God-given, and given to all “MEN.” Jefferson knew that it was only a matter of time before the Constitution would bend on the issue of slavery, as slavery was an institution at odds with the natural state of affairs, and God’s justice, he says in Query XVIII, “cannot sleep for ever.” And so his attachment to the right of each state to determine for itself the issue of slavery was provisional. For Early, the Constitution’s silence on the issue was the final word, and that seems somewhat desperate.

In sum, the problem with Old Jube’s efforts to vindicate the South by showing that their participation in the war was due to states’ rights, not slavery, is that the two issues, theoretically distinct, were in praxis intertwined. One sees that quite plainly in the general’s many arguments in The Heritage of the South on behalf of the South not entering the war on account of slavery.

Yet Northerners, and enlightened Southerners like Jefferson, were increasingly coming to see that no group of humans ought to have the status of property to another group—that slavery was one issue that ought not to be swept under the states’-rights rug. One large reason for that illumination was the global respect won by Thomas Jefferson’s own Declaration of Independence over the years and its unbending assertion of the moral equality of all persons.

M. Andrew Holowchak, Ph.D., is a philosopher and historian, editor of “The Journal of Thomas Jefferson’s Life and Times,” and author/editor of 11 books and of over 80 published essays on Thomas Jefferson. He can be reached through https://www.thomasjeffersonsage.com.