When Edward Gibbon embarked on his great history of the decline and fall of the Roman Empire, he began his narrative with the accession of Commodus. Marcus Aurelius, the father of the new emperor, was a man who, in the noblest traditions of the Roman people, had combined the attributes of a warrior, a statesman, and a philosopher; Commodus was none of these.

“The influence of a polite age, and the labour of an attentive education,” Gibbon wrote sternly, “had never been able to infuse into his rude and brutish mind, the least tincture of learning; and he was the first of the Roman emperors totally devoid of taste for the pleasures of the understanding.” Instead, Commodus delighted in trampling on the standards by which the Roman political class had traditionally comported themselves. Most shockingly of all—as everyone who has seen Gladiator will remember—he appeared in the arena. His reward for this spectacular breach of etiquette was the cheers of the plebs and the pursed-lipped horror of the senatorial elite. To fight before the gaze of the stinking masses was regarded by all decent upholders of Roman morality as the most scandalous thing that a citizen could possibly do—but Commodus reveled in it. So it was, as Gibbon put it, that he “attained the summit of vice and infamy.”

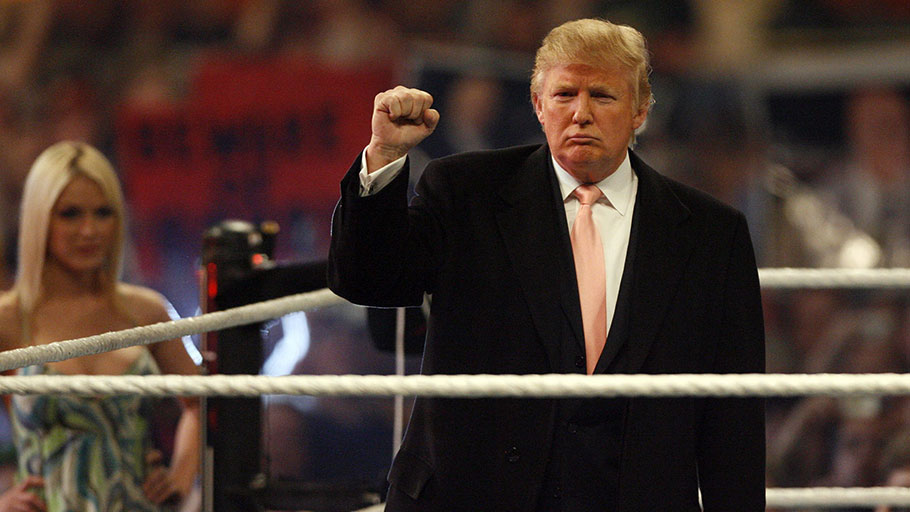

Today, when conservatives contemplate a leader who, far from being merely an enthusiast for World Wrestling Entertainment, has long been an active and flamboyant participant in it, they may experience” a similar shudder. Donald Trump, the only president of the United States ever to have been inducted into the WWE Hall of Fame, boasted that he had won “the highest ratings, the highest pay-per-view in the history of wrestling of any kind.” The Battle of the Billionaires—a proxy wrestling match fought in 2007 between Trump and Vince McMahon, the owner of WWE—had culminated in a victorious Trump strapping McMahon to a barber’s chair and shaving him bald. A decade later, Trump made clear just how much of an influence the theatrical violence of WWE had had on his approach to politics when he tweeted a video of himself body-slamming and repeatedly punching McMahon.

Donald Trump before his “Hair vs. Hair” bout with wrestling promoter Vince McMahon in WrestleMania 23, Detroit, Michigan, April 1, 2007. Leon Halip/WireImage/Getty Images

It was in a similar spirit, perhaps, that Commodus might have posed after decapitating an ostrich. Trump, smacking home his point, made sure before he tweeted the video to specify who his real target was. Clumsily superimposed over McMahon’s face was the CNN logo. “FraudNewsCNN” ran the hashtag. “The speed with which we’re recapitulating the decline and fall of Rome is impressive,” the conservative intellectual and former editor of the Weekly Standard Bill Kristol tweeted in response. “What took Rome centuries we’re achieving in months.”

The conviction that Trump is single-handedly tipping the United States into a crisis worthy of the Roman Empire at its most decadent has been a staple of jeremiads ever since his election, but fretting whether it is the fate of the United States in the twenty-first century to ape Rome by subsiding into terminal decay did not begin with his presidency. A year before Trump’s election, the distinguished Harvard political scientist Joseph Nye was already glancing nervously over his shoulder at the vanished empire of the Caesars: “Rome rotted from within when people lost confidence in their culture and institutions, elites battled for control, corruption increased and the economy failed to grow adequately.” Doom-laden prophecies such as these, of decline and fall, are the somber counterpoint to the optimism of the American Dream.

And so they have always been. At various points in American history, various reasons have been advanced to explain why the United States is bound to join the Roman Empire in oblivion. In 1919, in the wake of the Russian Revolution, The New York Times warned that the Huns and the Vandals were massing again. “The Roman Empire and its civilization were destroyed by barbarian hordes coming from the East—and it is from the east that comes the wind.” Thirty years earlier, visiting the abandoned Roman city at Baalbek in Lebanon, Brooks Adams—the great-grandson of John Adams—had been inspired by the spectacle of shattered greatness to dread that his own country’s gilded age was bound to end in similar ruin. In the decades before the Civil War, opponents of slavery repeatedly cited the fall of Rome as a warning of what might happen to a slave-owning society. In the 1830s, opponents of Andrew Jackson cast him as a dictator and a demagogue whose tyranny would inevitably bring the infant republic to share in the fate of the ancient empire. Present anxieties that Trump’s presidency portends America’s decline and fall are the contemporary expression of a tradition quite as venerable as the United States itself.

Just as Americans today look back wistfully to the Founding Fathers as patrons of an age of rugged independence and virtue, so did the Founding Fathers look back with an equal wistfulness to the early years of Rome. There, for any young republic victorious in a war against a great monarchy, a morality tale was to be found that could hardly help but serve as inspiration. The Romans, like the Americans, had originally been ruled by a king; then, resolved no longer to live in servitude, they had dared in a heroic and ultimately successful campaign to expel him. Repeatedly, whether by standing alone on a bridge against fearsome odds, or by plunging a hand into fire rather than submit to tyranny, or by riding a horse into a bottomless abyss in the certainty that such a sacrifice would secure the republic against ruin, Romans had demonstrated their commitment to liberty.

Statue of George Washington by Horatio Greenough in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, Washington, D.C. – US Congress

So, at any rate, it was recorded in the classics of Roman literature that were a staple of elite education in the thirteen colonies. The appeal that exemplars such as the pages of Livy had to offer American readers was, in the wake of the revolutionary war, very evident. “Soon as this great work was done,” wrote Parson Weems, author of the first biography of George Washington, “he took an affectionate leave of his gallant army and returned to cultivate his four acres.” Weems, though, was not describing Washington, but Cincinnatus, an upright Roman statesman who, summoned from his plough to save his city from invasion, had, once his duty was done, laid down his office and returned to his plough. In 1832, commissioned to mark the centennial of Washington’s birth with a fittingly imposing statue, the sculptor Horatio Greenough represented him as just such a hero, returning his sword to a grateful people. Simultaneously toga-clad and bewigged, the first president of the United States was portrayed by Greenough as the heroic, if sartorially challenged, intersection point of twin republics: the Roman and the American.

Yet to admire the antique virtues of Rome, those same qualities of rugged patriotism that, according to the Romans themselves, had prevailed in the city before overseas conquests flooded it with luxuries and made plutocrats of its greatest men, was to dread as well that it might all go wrong. Benjamin Franklin, asked as he left Independence Hall whether America was to have a republic or a monarchy, had famously answered, “A Republic—if you can keep it.” He, like everyone else at the Constitutional Convention, was all too painfully aware that Rome’s liberty had ended up crushed beneath the weight of her own greatness; the Caesars had raised a tyranny over its corpse. The Roman people, no longer ploughing their fields as Cincinnatus had done, virtuous and free, had degenerated into a feckless rabble, sustained by hand-outs and grotesque entertainments. Barbarians had come sweeping in. The Senate had been swept away. The Capitol had been lost to weeds. Barefoot friars sang vespers in the Temple of Jupiter. Here, for Franklin and all the Founding Fathers, was a narrative that could hardly help but serve their fledgling republic as a terrible warning.

Americans, of course, were not alone in looking to the ancient past and shivering. The first volume of Gibbon’s great history had been published only a few months before the outbreak of the American Revolution, and the author, gazing across the Atlantic, could not help but be morosely conscious of the disaster looming before his country. “The decadence of the two empires,” he wrote, “Roman and British, proceeds in step.” In the event, of course, Britain’s monarchy did not doom it to ruin, nor did the loss of the thirteen colonies spell the end of her global ambitions. Throughout the nineteenth century, the continued expansion of the British Empire served as reproof to any notion that republicanism might be a necessary precondition for a people to flourish. Even so, precisely because the circumstances of their country’s founding seemed to map so closely onto the contours of Rome’s early history, Americans never entirely shook the assumption. Gibbon’s argument in The Decline and Fall—that the collapse of the Roman Republic had made the ultimate collapse of the Roman Empire as well inevitable—was one that they were primed to accept: “Prosperity ripened the principle of decay; the cause of destruction multiplied with the extent of conquest; and, as soon as time or accident had removed the artificial supports, the stupendous fabric yielded to the pressure of its own weight.” American self-confidence has never entirely escaped the shadow of a nagging fear: that greatness fosters autocracy, and autocracy fosters doom.

This is why, perhaps, faced by the rampant egotism and swagger of a showman like Trump, his opponents can often seem less alarmed by his policies than by his style. Nostalgia for a more dignified and marmoreal style of politics, one that might indeed seem descended from the age of the Founding Fathers, has been a constant among critics, Democrats as well as Republicans. Nowhere was this more evident than at the funeral of John McCain, whose record of heroism as a soldier and of patriotism as a senator Cincinnatus might well have admired. The presence among the mourners of assorted heavyweights from across the political divide, including three presidents, seemed a reproof to the absent Trump: an attempt to marshal what the Romans would have termed “mos maiorum,” ancestral custom, against the presidential cuckoo in the nest. McCain’s daughter, addressing the mourners, made sure to render this explicit. “He understood our republic demands responsibilities even before it defends its rights,” she declared. “The America of John McCain has no need to be made great again because America was always great.” Here were sentiments that would have adorned the pages of Livy.

The newly crowned Emperor Commodus, played by Christopher Plummer, entering the Forum in a scene from the 1964 film The Fall of the Roman Empire

Nevertheless, it can be a mistake to take Roman historians entirely at their own estimation. Commodus, with his flamboyant mockery of traditional proprieties, was himself heir to a venerable tradition. Back in the dying days of the Roman Republic, it had pleased the conservative senators who defined themselves as “optimates,” the best, to disparage their opponents as “populares”: populists. Yet the popularis tradition was one which, no less than their own, had long been part of the fabric of Roman politics. That it came to be weaponized by a succession of notorious Caesars—Caligula, Nero, Commodus himself—did not mean that it was necessarily incompatible with the functioning of a republic. The realization that mockery of elites and the trampling of political convention might be transmuted into popularity with the plebs had not inevitably doomed Rome to autocracy. Populares no less than optimates had been part of the fabric of a free state.

History serves as only the blindest and most stumbling guide to the future. America is not Rome. Donald Trump is not Commodus. There is nothing written into the DNA of a superpower that says that it must inevitably decline and fall. This is not an argument for complacency; it is an argument against despair. Americans have been worrying about the future of their republic for centuries now. There is every prospect that they will be worrying about it for centuries more.

Featured Image: Thomas Cole, The Course of Empire: Destruction (1836). Collection of the New-York Historical Society/Bridgeman Images