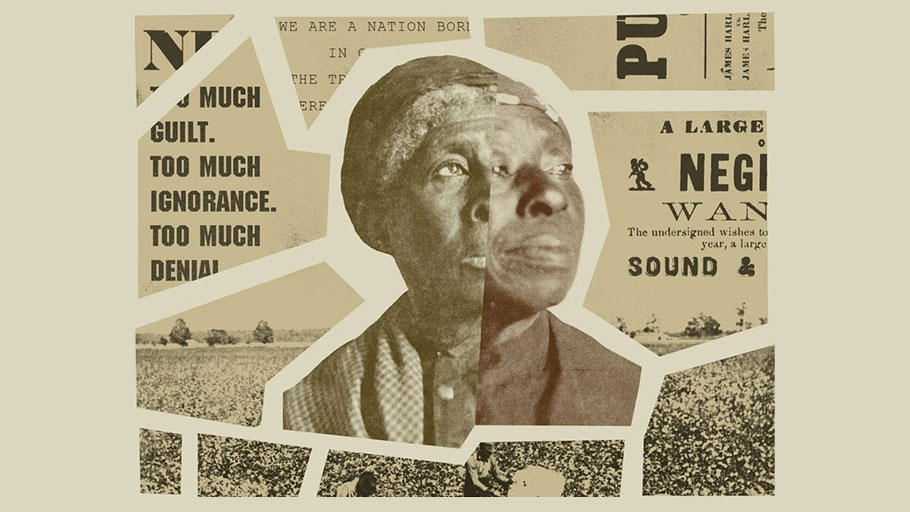

Teaching America’s truth

For generations, children have been spared the whole, terrible reality about slavery’s place in U.S. history, but some schools are beginning to strip away the deception and evasions.

By Joe Heim, The Washington Post —

Pacing his classroom in north-central Iowa, Tom McClimon prepared to deliver an essential truth about American history to his eighth-grade students. He stopped and slowly raised his index finger in front of his chest.

“Think about this. For 246 years, slavery was legal in America. It wasn’t made illegal until 154 years ago,” the 26-year-old teacher told the 23 students sitting before him at Fort Dodge Middle School. “So, what does that mean? It means slavery has been a part of America much longer than it hasn’t been a part of America.”

It is a simple observation, but it is also a revelatory way to think about slavery in America and its inextricable role in the country’s founding, evolution and present. Ours is a nation born as much in chains as in freedom. A century and a half after slavery was made illegal — and 400 years after the first documented arrival of enslaved people from Africa in Virginia — the trauma of this inherited disease lingers.

But telling the truth about slavery in American public schools has long been a failing proposition. Many teachers feel ill-prepared, and textbooks rarely do more than skim the surface. There is too much pain to explore. Too much guilt, ignorance, denial.

It is why, just four years ago, textbooks told students “workers” were brought from Africa to America, not men, women and children in chains. It is why, last year, a teacher asked students to list “positive” aspects of slavery. It is why, even in 2019, there are teachers in schools who still think holding mock auctions is a good way for students to learn about slavery. Misinformation and flawed teaching about America’s “original sin” fills our classrooms from an early age.

And yet as issues of race and prejudice and privilege continue to roil America, an understanding of how slavery forged the country seems all the more necessary.

Many of the Democratic presidential candidates say the nation should explore whether to pay some form of reparations to descendants of enslaved people — an issue that has been off the radar in previous presidential campaigns. And the rise of violence and vitriol fueled by white supremacy over the past decade — from the Charleston, S.C., church massacre to torchlight marches and murder in Charlottesville to the casual racism of public officials and leaders — reinforces the need for a deeper understanding of how slavery fostered and upheld that belief system.

A range of critics — historians, educators, civil rights activists — want to change how schools teach the subject. The evidence of slavery’s legacy is all around us, they say, pointing to the persistence of segregation in schools, the gaping racial disparities in income and wealth, and the damage done to black families by the U.S. criminal justice system. According to a 2018 report to the United Nations by the Sentencing Project, a nonprofit organization that advocates reducing racial disparities in prison sentences, American judges will send one in three black boys born in 2001 to prison in their lifetimes, compared with one in 17 white boys born the same year.

The failure to educate students about slavery prevents a full and honest reckoning with its ongoing cost in America. Teaching the truth about slavery, critics argue, could help remedy that. But that means acknowledging and exploring slavery’s depravity. It means telling the personal stories of enslaved people, the physical and psychological cruelty they endured, the sexual violence inflicted upon them, the separation of husbands and wives, parents and children.

A drawing of a slave ship hangs in Tiffany Classie Williams’s history class at Huffman High School in Birmingham, Ala., in April. (Julie Bennett for The Washington Post)

The difficult truth means explaining to students not just how this practice of institutionalized evil came to be but also how it was accepted, embraced and inculcated in American daily life since enslaved Africans were brought to Jamestown, Va., 400 years ago. Slavery was not accepted by everyone, of course, but by enough that it was protected by laws, reinforced by practice and justified or excused in all corners of the country.

For the 50 million students attending public school in America, how they are taught about America’s history of slavery and its deprivations is as fundamental as how they are taught about the Declaration of Independence and its core assertion that “all men are created equal.” A deep understanding of one without a deep understanding of the other is to not know America at all.

McClimon wanted the hard lessons about slavery to sink in as he led students through course work that didn’t shrink from describing its horrors. He showed them a photo of an enslaved man so severely whipped that his back was more scar tissue than smooth skin. They watched Hollywood actors read devastating personal accounts of former slaves, some of whom had been separated from loved ones they would never see again. They discussed resistance, escapes, uprisings.

At Fort Dodge Middle School in Fort Dodge, Iowa, Tom McClimon in March listens to eighth-graders Kyron Wilson, left, and Kade Nielsen as they discuss the lasting effects of slavery. (Rachel Mummey for The Washington Post)

“A lot of times we forget that as soon as slavery started, enslaved people were fighting back,” McClimon told the students, a lesson that contradicts the idea, often taught in the last century, that enslaved people endured their lot complacently, sometimes even happily. Later, McClimon, who is white, urged his students to examine how white supremacy allowed slavery to flourish, and he asked, “Is our idea of white supremacy different now than it was then?”

The history of slavery McClimon teaches bears almost no resemblance to the history he learned as a middle school and high school student a little more than a decade ago. Then, he said, teachers spent a day or two on slavery. It was discussed primarily as a factor in the Civil War. Not much else.

In many ways, McClimon’s experience as a student was, and still is, typical. But it is not the approach the Fort Dodge Community School District has embraced. Two years ago, the district started teaching slavery as fundamental to America’s growth, wealth and identity rather than as a tangential part of the country’s history. Slavery would be emphasized and fully explored, not avoided or downplayed.

Throughout the 20th century, textbooks often glossed over slavery, treating it not as central to the American story but as an unfortunate blemish washed away by the blood of the Civil War. Students rarely learned that slavery had for a time been prevalent in the North or that the economy of the North was long reliant on the South’s slave-labor production. The enslavement of Native Americans, which predates the arrival of the first enslaved Africans, was mentioned only in passing, if at all.

Many baby boomers were fed tales in school that masked the reality of slavery. Some teaching even emphasized the idea that Africans brought here in chains were actually better off.

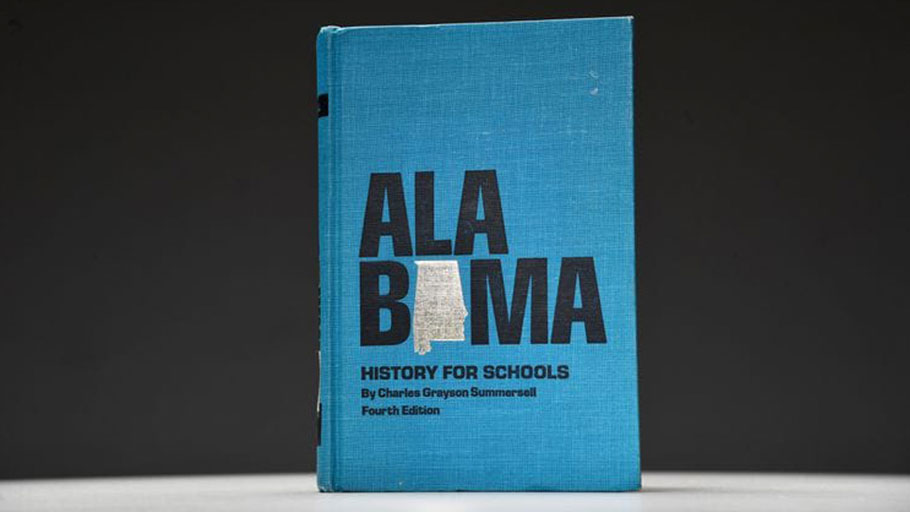

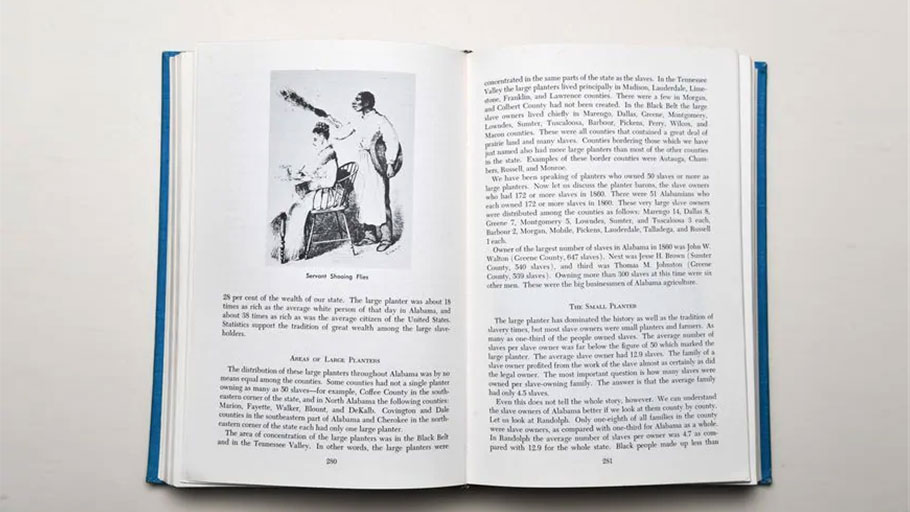

Throughout the 20th century, school textbooks often glossed over slavery or tried to spin it as positive for enslaved people. (Marvin Joseph/The Washington Post)

(Marvin Joseph/The Washington Post)

“With all the drawbacks of slavery, it should be noted that slavery was the earliest form of social security in the United States,” students read in Alabama history textbooks of the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s. And there was this: “A jail sentence or the execution of a slave was considered to be more of a punishment for the master than for the slave, because the slave was such valuable property.”

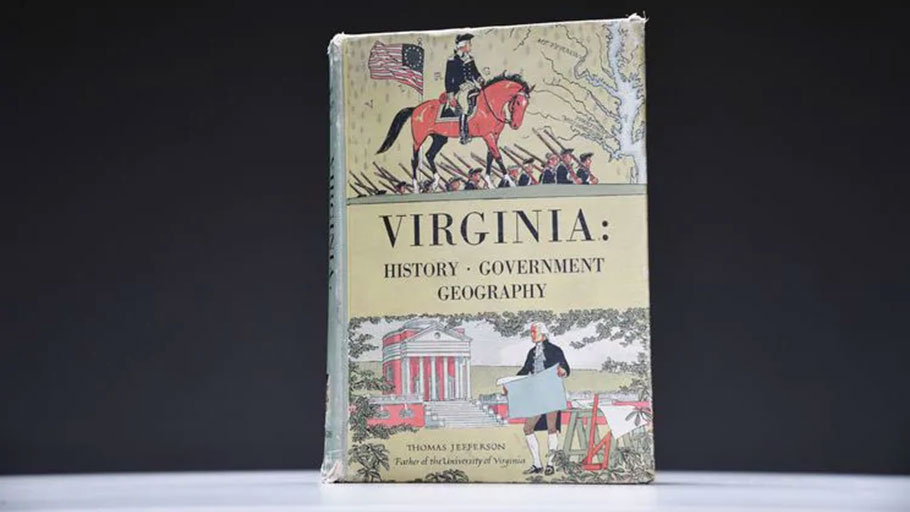

A Virginia textbook of the same era told students that Virginia “offered a better life for the Negroes than did Africa. In his new home, the Negro was far away from the spears and war clubs of enemy tribes. He had some of the comforts of civilized life.”

The punishment of enslaved people was described as rare and unfortunate, but necessary. “Most masters did not want to punish their slaves severely,” the Virginia textbook read. “In those days whipping was also the usual method of correcting children. The planter looked upon his slaves as children and punished them as such.”

Confederate apologists in the early 20th century worked to remove negative portrayals of the South from textbooks and history books. (Marvin Joseph/The Washington Post)

(Marvin Joseph/The Washington Post)

These benevolent depictions of slavery were not a matter of happenstance. They were a direct result of efforts by Confederate apologists in the early 20th century to remove negative portrayals of the South from textbooks and history books. In 1920, Mildred Lewis Rutherford, an educator and historian of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, wrote “A Measuring Rod to Test Text Books, and Reference Books in Schools, Colleges and Libraries,” a guide distributed throughout the South that proposed strict rules for what could be included in books for Southern students.

“Reject a book that says the South fought to hold her slaves,” Rutherford wrote. “Reject a book that speaks of the slaveholder of the South as cruel and unjust to his slaves.”

It was a reeducation campaign that made lies of truth. In fact, states that seceded from the Union made clear that they fought to hold their slaves. Soon after his election as president of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis said: “We recognized the Negro as God and God’s Book and God’s laws, in nature, tell us to recognize him. Our inferior, fitted expressly for servitude … You cannot transform the Negro into anything one-tenth as useful or as good as what slavery enables them to be.”

By the last two decades of the 20th century, many of the more egregious falsehoods and excuses regarding slavery were removed from textbooks. But getting at the truth was still elusive. The narrative of slavery became more notable for what it didn’t say than what it did.

Philip Jackson, an American history teacher in Montgomery County, Md., remembers learning little about slavery when he attended public school in the late 1970s and early 1980s in the same county where he now teaches.

U.S. history teacher Philip Jackson teaches the history of slavery to his eighth-graders at Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Middle School in Germantown, Md., in February. (Ricky Carioti/The Washington Post)

“Pretty much all anyone knew about slavery was ‘Gone with the Wind,’ ” Jackson, who is African American, said in his classroom at Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Middle School in Germantown, Md., a growing suburb north of Washington. “I don’t remember ever going into any depth about slavery other than that there was slavery. The textbooks were pretty whitewashed. We never talked about the conditions of slavery or why it persisted.”

For Jackson and many students of the time, the most in-depth learning they had about slavery came from watching “Roots,” the 1977 miniseries — based on the Alex Haley novel — that was shown for years in classrooms throughout the country. Jackson’s experience is similar to that of several generations of Americans. If they remember being taught about slavery at all, they don’t recall its importance being emphasized, and they certainly were not told that slavery was part of the foundation on which America was built.

It would be some solace to know that the dubious scholarship and outright lies that informed instruction about slavery for millions of students throughout the 20th century were things of the past. But false or misleading lessons about slavery aren’t confined to dusty tomes or the classrooms of yesteryear. A textbook used by a Texas public charter school chain in the 2000s taught: “While there were cruel masters who maimed or even killed their slaves (although killing and maiming were against the law in every state), there were also kind and generous owners … Many [enslaved people] may not have even been terribly unhappy with their lot, for they knew no other.”

“I don’t remember ever going into any depth about slavery other than that there was slavery. The textbooks were pretty whitewashed. We never talked about the conditions of slavery or why it persisted.” — Philip Jackson

And rarely a semester passes without news of students being taught about slavery through a reenactment of a slave auction, a physical education class that requires kids to run an obstacle course while pretending to flee slavery, or a math problem that asks third-graders such questions as: “A tree had 56 oranges. If eight slaves pick them equally, then how much would each slave pick?” and “If Frederick got two beatings per day, how many beatings did he get in one week?”

These incidents almost always prompt outrage and are followed by apologies. And yet they continue. That they have not disappeared, critics say, is a sign that lessons aren’t being learned and that many teachers lack a critical understanding of slavery and how to teach about it. The furor that erupts also points to how incendiary the issue is and, in many ways, how little the country has done to reconcile with its legacy.

“Teaching about slavery is a loaded subject, and it’s loaded because everyone knows that it’s not really about the past,” said Maureen Costello, director of Teaching Tolerance, a civil rights education project of the Southern Poverty Law Center. The nonprofit released a study last year examining how students are taught about slavery and suggesting ways to improve that education.

The study, “Teaching Hard History,” found that students were not learning nuanced and many-layered lessons about slavery. And they were often not learning basic facts.

Included in the report was a survey of high school seniors that revealed a fundamental lack of knowledge about various aspects of slavery. Few identified slavery as the primary cause of the Civil War. And the majority of respondents were not able to identify the middle passage as the transatlantic journey endured by 12 million Africans who were brought to the Americas and Caribbean, chained together and crammed into the holds of ships. Even fewer who took the survey correctly answered that it took a constitutional amendment to bring slavery to an end.

The “Teaching Hard History” report called out American schools for failing to teach the “breadth and depth” of how slavery came to be and how it continues to manifest itself in America. It issued a withering rebuke of a dozen middle and high school textbooks for their inadequacy in explaining slavery and its ongoing impact. And it offered guidance for teaching that addresses the experiences of enslaved people, the economics behind the enterprise, the rationales for its existence, including white supremacy, the resistance it spawned and how its legacy remains with us.

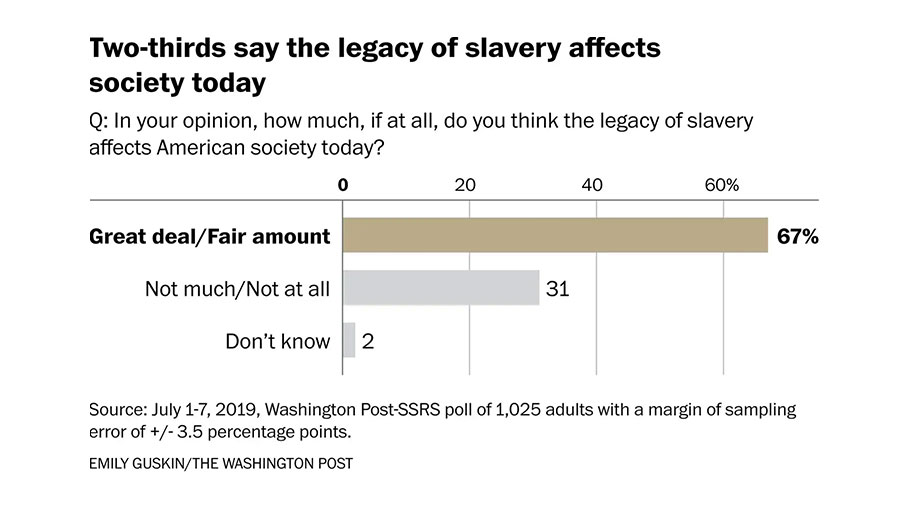

A Washington Post-SSRS poll this summer showed that just under half of Americans know that slavery existed in all 13 colonies. As for the Civil War, 52 percent said that slavery was the main cause, while 41 percent said it was something other than slavery.

If slavery hasn’t been particularly well taught, Americans still believe that its legacy continues to be felt. Sixty-seven percent said slavery affects U.S. society today either a great deal (31 percent) or a fair amount (36 percent). Eleven percent said it has no effect today.

Exploring that legacy has been eye-opening for many students The Post interviewed.

Exploring that legacy has been eye-opening for many students The Post interviewed.

“Obviously, there’s not slavery anymore, but the effects of it and the racial tensions, we still see today,” said Alexandra Steffens, who graduated in June from Concord Middle School in Concord, Mass.

Steffens, who is white, spent a large chunk of her eighth-grade history class studying the history of slavery in America.

“A lot of times, you learn about slavery, but you don’t learn about the actual cruelties of it, and you just kind of see it as a big thing and not in individual acts,” she said.

Amari Bennet, who graduated in May from Ramsay High School in Birmingham, Ala., said that instances of police brutality toward African Americans and mass incarceration of blacks reinforce her sense that the past is still very much with us.

“Studying slavery kind of shows how we ended up where we are now,” said Bennet, who is black. “Even though we’ve progressed to such a vast extent from slavery times, we still have issues with civil rights that we’re dealing with today.”

Featured image: Illustration by Joan Wong for The Washington Post/Images from New York Public Library