Photo: Meharry’s students and staff have worked together to conduct drive-thru testing and screening for the coronavirus. Meharry Medical College

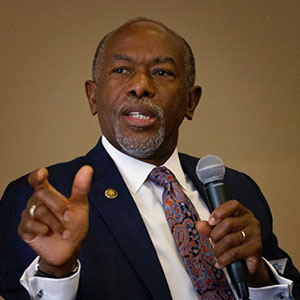

Meharry Medical College President James Hildreth has been advocating for advanced or pre-emptive screening in black neighborhoods for weeks.

Meharry Medical College was founded in 1876 in Nashville, Tennessee, to teach medicine to former enslaved Africans and to serve the underserved. Now, in one of its laboratories, a scientist says he is two weeks away from testing an anti-virus to prevent COVID-19, the disease ravaging many African American communities across the country.

“And that makes us all at Meharry compelled to do our best,” the scientist, Dr. Donald Alcendor, who worked a few years ago on a successful anti-virus to the Zika virus, told NBC News.

In other words, it’s personal.

“This is bigger than COVID-19,” said Dr. Linda Witt, the senior associate vice president for development at Meharry, a historically black college, or HBCU. “We are called to serve on the front lines. For Meharrians, it’s natural to go into our communities. We exist in the black community. But it’s at a heightened level now. And having an HBCU presence, voice and expertise is essential.”

Alcendor said the irony of the social distancing and shelter-in-place guidelines is that he now has the time to enter Meharry in the global race to find treatment for COVID-19. Pharmaceutical companies and countless scientists, including at the University of North Carolina and Vanderbilt, are scurrying to create a drug to offset the disease. Alcendor, at the behest of Meharry President James E.K. Hildreth, embraces his role in the competition.

Dr. Donald Alcendor. Meharry Medical College

“Usually, we all wear different hats and do various jobs,” Alcendor said. But recently he has been strictly in the lab. And the success of the Zika virus antiviral drug has made him optimistic that his work could help quell tension and drastically lower the death rate. A vaccine, which prevents contracting the disease, will take up to 18 months to produce, Alcendor and other scientists said, while an antiviral drug would be used to treat patients once infected.

“The process is understanding how the virus gets into your system, where it goes and how it infects,” Alcendor said about developing an antiviral drug. “The struggle is that it is a single-strand that produces tremendous inflammation. The patient will feel like he’s drowning.”

Alcendor’s antiviral drug or reagent, he said, would “intervene at the critical point in the virus’ (attack), eliminating its ability to reproduce viral proteins. The cycle would be terminated.”

“It’s similar to what we did with Zika,” he added. “But in comparison to Zika, this is through the roof. We didn’t have the deaths or the spread. This is a much bigger scale. All the marbles are on the table.”

He hopes to have the anti-viral treatment created in the next two weeks. It will then move on to clinical trials and, if successful, be approved by the Food and Drug Administration within a “few months.”

While that is significant, it is not unlike the work Meharry has done for centuries in producing more than 4,800 black doctors, 83 percent of whom work in black or underserved communities.

In every facet, “the Meharry family” is working in communities-of-need to offset gross health disparities. A recent report by ProPublica indicates black people have tested positive and died from the coronavirus at a higher rate than any other racial or ethnic group in the United States.

Dr. James Hildreth. Meharry Medical College

Dr. James Hildreth has been advocating for advanced or pre-emptive screening in black neighborhoods for weeks. An infectious disease scientist, Hildreth knew the highly contagious coronavirus was most volatile in people with existing health concerns like diabetes, high blood pressure, asthma and other issues that are prevalent in African American communities, in large part because of the dramatic health care and environmental disparities in the United States.

“I have been pushing for pre-emptive screening with health officials going into the underserved communities to start testing because that would be a way to get in front of it with the most vulnerable public,” Hildreth said. “If you have pre-existing auto-immune disease and the other stated health issues, the outcomes are much more severe. Those are exactly what we have in our communities. The burden of the disease is so much higher.”

Meharry has administered free drive-up coronavirus tests and screening on its campus. The opportunity is open to all residents in the area, but those who live in the northern part of the city, where the largest concentration of African Americans reside, have taken advantage of it.

“People are scared,” Cherae Farmer-Dixon, a dean and professor at Meharry’s School of Dentistry, said. “There was a young lady who came in for testing. She was in a car full of individuals. She was in tears. She had been around someone who had tested positive and she didn’t want to bring it around her grandmother if she was positive. For her and others, to see people who look like them serving, administering the tests, being there, it made all the difference.”

Meharry is able to bridge the lack-of-trust factor that permeates the black community because of its long-standing reputation as a go-to place for black residents seeking talented black doctors.

Meharry Medical College has the highest percentage of African Americans graduating with PhDs, in the biomedical sciences, in the country. Meharry Medical College

“What makes this so special is that everyone is chipping in, volunteering,” said Rahwa Mehari, the college’s development officer. “Everyone is doing this on their own. It’s part of the culture. The students help, even if it’s directing traffic (for the drive-thru testing and screening).”

This call to action is a continuation of a harrowing two months that have tested Meharry’s collective resolve. Days after administering free dental services for 500 people in the community on Oral Care Day, a tornado roared through Nashville and inflicted much damage, especially on the north side of town.

The school set up a Mobile Health Unit, where students, faculty and staff of Meharry went door-to-door to do health and wellness checks, and offer complimentary care where needed.

“In the black family, everyone played its role,” Witt said. “That’s what we do.”

There are many examples: At Stanford University, Meharry graduate Dr. Italo Brown works on the front lines of the COVID-19 response in California, serving mostly black and brown patients.

Dr. Armen Henderson, a 2014 Meharry graduate, treats and tests homeless people in Miami for the coronavirus. Dr. Jay-Sheree Allen works in rural Minnesota, leading the preparation for the pending onslaught of cases and for supplying personal protection equipment. She also hosts a podcast called Millennial Health, which features black doctors sharing health care and COVID-19 information.

In Holly Springs, Mississippi, 1986 Meharry grad Kenneth Williams purchased two hospitals that serve the indigent African American community. His daughter, also a Meharrian, is the chief resident at Tulane University in New Orleans, which has been hit hard by COVID-19

And then there’s Dr. Elvis Francois, an orthopedic surgeon at Mayo Clinic in Minnesota whose video of him singing to alleviate stress during the tension of the coronavirus was an internet favorite.

Amid all this, Witt said, “we always need financial support, donations. We work on a tight budget. But it’s the work we are called to do.”

Added Farmer-Dixon: “So many times, the black community feels forgotten or left out. Well, we make sure we are a part of communities across the country. People know we are here, intimately touching those who often feel untouched. It’s amazing to see. But it’s what Meharry was founded on.”

This article was originally published by NBC News.