Illustration by Emma Ruck

From indentured servitude to federal redlining, Evanston’s history is marked with colored lines. City officials and residents develop initiatives to address historical inequities with the recently established reparations fund.

By Keerti Gopal, The Daily Northwestern —

Maria Murray was 15 years old in 1855 when she was purchased out of slavery by a white family and brought to work as an indentured servant in their Evanston home. She was one of Evanston’s first black residents.

Evanston native and historian Dino Robinson said newspapers diminished Murray’s status as an indentured servant, calling her “a friend of the family” she served.

“How can you really say that?” Robinson said. “When a person (was) purchased out of slavery … and brought to Evanston to work the remainder of her life?”

In November 2019, Evanston established a reparations fund to address generations of institutional disenfranchisement against black residents. The fund draws from a 3 percent tax on recreational marijuana — set to begin collection July 1 — as well as from private donations.

Ald. Robin Rue Simmons (5th), who has led the push for reparations in Evanston alongside a City Council subcommittee and the city’s Equity and Empowerment Commission, said she is motivated to fight for reparations by the persisting racial disparities she sees in the city.

“The disparities continue to rise and our black population has been on a steady decline,” Rue Simmons said. “It was (that) information that led me to urgently pursue policy as radical as the terrible actions that got us to this place of disparity, and reparations is the answer.”

The city plans to commit $10 million to the fund over the next 10 years. Rue Simmons said reparations will be enacted through targeted initiatives focused on housing, business and education.

A forgotten debt

The idea of modern reparations stems from Union general William T. Sherman’s national call in 1865 to redistribute 40-acre plots of Southern land to freed black families and, later, to authorize loaning mules to freedmen working as farmers — known today as “40 acres and a mule.” However, President Andrew Johnson overturned the order that same year, reinstating most of the land to its previous white owners.

Growing up in Evanston, Meleika Gardner remembers talking about that debt with her family around the Sunday night dinner table.

“The 40 acres and a mule was owed to us, and we never got it,” Gardner said. “That’s what I understand about reparations. It is generations of pain that have not been dealt with, injustice that has not been dealt with.”

HR 40, a bill proposing a federally funded study into the possibility of reparations, was introduced by former Rep. John Conyers (D-Michigan) continuously from 1989 to his retirement in 2017. In 2019, Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee (D-Texas) took up the bill again. To this day, the bill has not received a vote, she said.

In 2002, a resolution passed in Evanston’s City Council affirming support and solidarity for HR 40, but the city did not implement a policy of its own.

In recent years, the notion of reparations has sparked renewed national controversy. A 2019 poll by the Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research found that although 60 percent of Americans believe that the history of slavery continues to affect black citizens today, only 29 percent believe the U.S. government should pay reparations. Those results were split heavily by race: 74 percent of black respondents supported reparations, while only 15 percent of white respondents did.

Now, Evanston is among a handful of smaller governments and institutions that, in the past decade, have taken steps toward enacting local versions of reparations. In 2015, the City of Chicago passed an ordinance to provide compensation to victims of police violence. In 2019, Georgetown University created a $400,000 fund for the descendants of almost 300 enslaved people sold by the University in the 1800s. Most recently, the California state Senate created a task force to research reparations and develop a proposal for the state.

Shadows of slavery

Robinson, who founded the Shorefront Legacy Center to investigate and disseminate the history of black residents of the North Shore, said any conversation about reparations must be grounded in a centuries-long history of racism and targeted disenfranchisement.

“How can we repair that trauma and the divestment that’s happened over and over again, and over generations and over decades?” Robinson said. “That is traceable…you can see just by action what’s been happening in this community for decades.”

When Murray worked as an indentured servant in Evanston, slavery was illegal in the state of Illinois. But Robinson said the practice of indentured servitude remained common through the late 1800s.

Ken Wesbrooks said that this history continues to impact black Evanston residents today.

“Going through the initial conversations with community members on the issue of reparations indicated a lot of trauma that the citizenry was experiencing relating to…the post-slavery syndrome,” he said. “I don’t believe blacks feel that they truly have a voice in the city.”

As Evanston’s black population increased, so did segregation

By 1880, about 125 black people lived in Evanston. As the Great Migration brought more black Americans north, Evanston’s black population grew: by 1960, the city was home to over 9,000 black residents.

In 1919, the city zoned almost every block populated by black residents for commercial uses, except for a portion of the West Side that would eventually become the 5th Ward. The city then demolished dozens of black-occupied homes. In the 1920s, Evanston aldermen began approving permit applications to relocate black households to the 5th Ward, according to city documents.

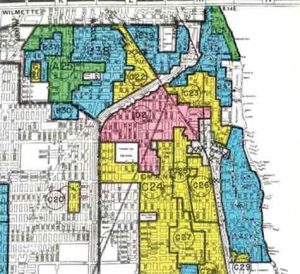

A 1940 map drawn by the federal Home Owners Loan Corporation showed the 5th Ward as the only area of Evanston marked with the lowest quality grade: a “D” for “detrimental influences” and an “undesirable population.”

1940 HOLC map ranking the neighborhoods of Evanston by desirability. The modern-day 5th Ward, highlighted in red, is classified as “undesirable” due to a significant black population. (Courtesy of City of Evanston)

“This concentration of negroes in Evanston is quite a serious problem for the town, as they seem to be growing steadily and encroaching into adjoining neighborhoods,” read one 1940 HOLC assessment discussing the modern-day 5th Ward. “The neighborhood is graded “D” because of its concentration of negroes, but the section may improve to a third class area as this element is forced out.”

“Racial steering” practices, where realtors would push black renters and buyers towards certain areas of the city — and away from others — continued in Evanston into the 1980s, according to city documents.

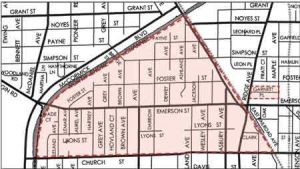

By 1940, 84 percent of black homeowners in Evanston lived in a triangular area that would become part of the 5th Ward. The area itself was 95 percent black. Now, according to data from 2010 Census data, 41.5 percent of 5th ward residents identify as black.

Robinson said questions of discrimination in housing and homeowner loans are still apparent in the 5th Ward, but are often hard to trace.

By 1940, 84 percent of Evanston’s black households fell within the shaded triangle, now part of the 5th Ward. (Source: Evanston RoundTable)

“I have (a) home in the 5th Ward,” Robinson said. “How do I know that the loan, the house loan that I have, the mortgage that I have, would have been fair and favorable to that of the white counterpart for the same credit line, same history, same job level? Would they have gotten a better percentage rate than me?”

Since 2000, Evanston’s black population has dropped from 22 to 16 percent, according to Census data. Equity and Empowerment Commission commissioner Delores Holmes said rising real estate prices have played a significant role in pushing out black families who have deep roots in the city.

“Everything comes back to housing,” she said of dialogues around reparations. “Coming up with solid plans for affordable housing, that would be the biggest thing.”

The city’s reparations subcommittee is considering initiatives to address housing disparities using the reparations fund, according to Rue Simmons.

She said policies will include both investing in new homeownership and preserving existing black ownership, through methods that might include providing in-need residents with relief for Cook County tax burdens and other direct benefits.

“(Housing is) the first and most likely route to building wealth in any community,” Rue Simmons said. “We are losing our black residents because of lack of affordable housing options to purchase and rent.”

Generational wealth disparities persist

The reparations subcommittee is committed to addressing the barriers that have historically prevented black Evanstonians from accumulating generational wealth, according to city documents.

Rue Simmons said these generational disparities cannot be reversed without policy targeted specifically at helping black residents.

“There is a 400-year headstart in the white community…wealth (that) was established in the slave trade that has passed down from generation to generation,” Rue Simmons said. “There’s no amount of hard work, bootstrapping, work ethic, education that can uplift the black community collectively to a place of equality.”

Gilo Kwesi Logan, an Evanston native and independent diversity and leadership consultant, said he has seen the impacts of this history on his own family. When Logan’s grandfather returned to Evanston after serving in World War II, he was denied the benefits of the GI Bill — like low interest mortgages and tuition stipends — because of his race, Logan said.

Without funding from the program, Logan said his grandfather wasn’t able to go back to school or invest resources into his home. When he compares the value of his grandfather’s home with the home of a white friend whose grandfather did qualify for the GI Bill, Logan said the disparities are clear.

“I look at the differences in my friend and I, and I can see some of that stems back to that one (difference),” Logan said. “That’s not the single cause of any of this, but that’s an example of some of the inequities that are playing themselves out even here in Evanston.”

In addition to housing, the reparations subcommittee is also examining opportunity gaps in business and education. According to city documents, unemployment in Evanston’s black community has risen from 5 percent to 15 percent since the 1960s, while overall unemployment has remained between zero and eight percent.

The median income for the 5th Ward ranges from $45,000 to $55,000, compared with Evanston’s overall median income range of $60,000 to $110,000. The 5th Ward also has the lowest property values in the city, lacks a public school and is the only ward with areas classified as food deserts, according to city documents.

Logan said addressing these disparities will take sustained, systemic change, and said he hopes the reparations fund becomes a permanent institution.

“Reparations is literally to repair the damage that has been done, and there has been great damage inflicted upon, particularly, the black community here in Evanston,” Logan said. “I’m talking about investment in the community and the people…and that’s a huge investment. That’s a multi-generational investment.”

COVID-19 underscores need for reparations

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted racial disparities in Evanston, particularly regarding access to health care and treatment for black residents, Wesbrooks said.

But the pandemic has also put increasing strain on the city’s finances, raising concerns about revenue and expenditures.

At an April City Council meeting, city staff suggested delaying the reparations fund to address the up to $20 million predicted in revenue loss.

“I absolutely support the spirit and the intent of what we’re doing with a reparations fund….(but) we are in a crisis right now as a city,” Mayor Steve Hagerty said. “We are going to absolutely significantly have to cut our expenses as a city.”

The proposal to postpone the reparations fund was met with pushback from aldermen and residents. On May 17, Rue Simmons made clear the city would move forward with reparations.

Rue Simmons told The Daily the city expects to receive revenue from the cannabis tax in September, and plans to begin enacting reparations by the end of the calendar year.

“My hope is that we can deliver our first reparations, our first direct or collective benefit to (a) black family in Evanston, in 2020,” she said.

Looking forward

At a town hall last Thursday, local and national leaders discussed the city’s reparations fund, and Jackson Lee expressed her hope that Evanston will provide inspiration for other cities nationwide.

“We applaud local jurisdictions who are taking this legislation and implementing it locally,” Jackson Lee said. “Those voices will be able to be the voices that will speak to us when the commission is established, and I have no doubt that we’re going to work to pass this legislation out of the United States House and the Senate.”

Rue Simmons said the reparations fund is a first step, but added that the $10 million dollars allotted to the fund will not be enough to reverse the city’s disparities. Robinson echoed that reparations will need to be more than a one-time initiative. Instead, he said, the city should formalize reparations as an institution.

“I’d like to see my kids come back to Evanston and see that there is an endowment totaling over 100 million dollars,” Robinson said. “Where 3 percent of that is used every year for big things that benefit the black community that has been disenfranchised in this country for 400 years.”

Source: The Daily Northwestern