Let’s keep it there.

By Salamishah Tillet and Scheherazade Tillet, The New York Times —

“I didn’t value the accusers’ stories because they were black women,” Chance the Rapper said in the final episode of Lifetime’s six-part documentary “Surviving R. Kelly,” which aired last week.

A few hours before the show, Chance wrote on Twitter: “Any of us who ever ignored the R. Kelly stories, or ever believed he was being set up/attacked by the system (as black men often are) were doing so at the detriment of black women and girls.”

Chance’s blunt admission has long been true. For 20 years, black girls and women accused the R&B singer Robert Kelly of sexually assaulting minors. Yet he still enjoyed enormous success.

So his spectacular fall — due in large part to the work of Dream Hampton, an executive producer of the documentary — marks a seismic cultural shift. Over the past week, we’ve had conversations with many people who had never believed black girls’ allegations against him until they saw the documentary (which the two of us, who are sisters, consulted on in its early stages).

It seems that #MeToo has finally returned to black girls. After all, #MeToo was founded by a black woman, Tarana Burke, to help African-American girls like the 13-year-old in Alabama who told her in 1997 about being sexually abused by her mother’s boyfriend. Now we have to make sure that it does not leave.

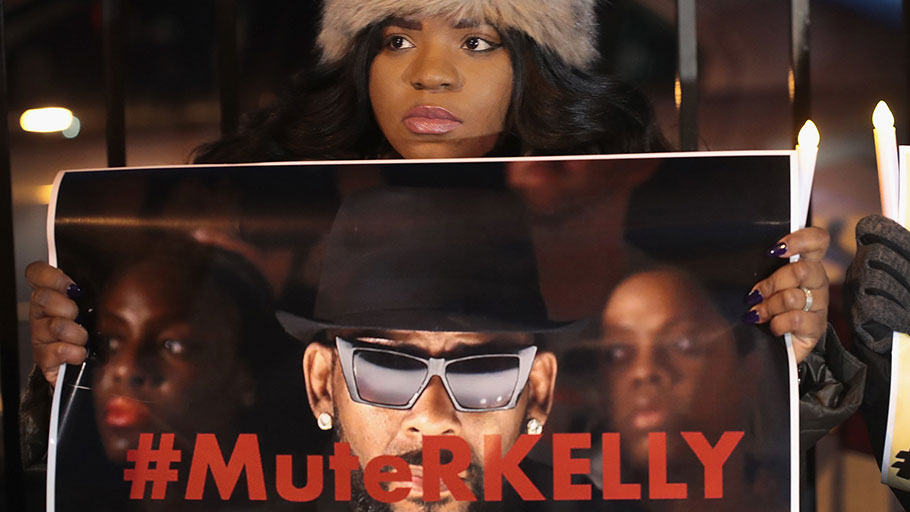

It’s clear that the tide has turned. The backlash against R. Kelly includes high-profile celebrities and everyday fans, as well as prosecutors in Atlanta and Chicago who are looking into the allegations and asking potential victims and witnesses to come forward. And it builds on the #MuteRKelly campaign; the cancellation of his concert last spring in Chicago, his hometown; and a statement by the Women of Color of Time’s Up demanding that companies like RCA Records, Spotify and Apple Music stop doing business with him.

But our optimism is tempered by history, which shows that social justice movements rarely center, for any meaningful period, on black girls, or anyone who has survived sexual violence. That’s because black girls experience racial, gender and economic oppressions all at the same time, a phenomenon the law professor Kimberlé Crenshaw calls intersectionality. As a result, their voices and experiences do not neatly fit into a single-issue narrative of gender or race.

Harriet Jacobs said as much in “Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl,” her landmark 1861 abolitionist narrative. “Slavery is terrible for men, but it is far more terrible for women,” she wrote to a predominantly white, female readership. She explained to them that a rite of passage for enslaved black girls was the threat of slave masters raping them. “I now entered on my 15 year — a sad epoch in the life of a slave girl,” she wrote. “My master began to whisper foul words in my ear.”

Though Jacobs’s memoir initially received favorable reviews, it fell into obscurity during the Civil War. Most academics considered it a work of fiction until 1987, when it was reissued; the historian Jean Fagan Yellin had rediscovered the book and proved its origins. Contrast that with Frederick Douglass’s memoirs, which “made him the most well-known Negro on the globe,” according to a 2018 book review in The Times.

As activists, we’ve also witnessed this firsthand. Twenty years ago, when we helped the filmmaker Aishah Shahidah Simmons make “NO! The Rape Documentary,” she was initially rejected by every major distributor. An executive from HBO even told her in 1998, “Let’s face it, very unfortunately, most people don’t care about the rape of black women and girls. And therefore, we’re concerned that there won’t be many viewers who will tune in to watch NO!, were we to air it on our network.”

Even today, as #MeToo continues to dominate headlines, black girls have been invisible in the movement. Instead, the media has primarily focused on white Hollywood actresses who have come forward with their accounts of systemic abuse and harassment.

But we learned through our work with A Long Walk Home, a nonprofit we founded in 2003 in response to Salamishah’s own experience of rape when she was 17, that one of the most overlooked yet effective ways to create social change is to just believe the stories that girls and young women of color tell us. And since black girls live at the crossroads of gender and racial violence, if we want to empower them, we have to confront and dismantle each system of oppression that affects them.

This past summer, for example, young artists and activists in our organization, which works to end violence against girls and women, led their first public art campaign, called “The Visibility Project.” They took over Douglas Park in Chicago, where several girls from their school had been abducted and later sexually assaulted. It’s also where a 22-year-old black woman, Rekia Boyd, was killed by an off-duty police officer in 2012.

As the girls shared their stories of sexual assault or gang violence, they refused to separate the impact of sexual violence, gun violence and political brutality on their lives and on their city. And there was a ripple effect. We’ve noticed in our work that black girls are very powerful organizers; they recruit boys, other girls, their parents and ultimately their community into the movement. That’s another reason we have to make sure that this current moment of listening to and believing black girls and young women is durable. If it’s fleeting, the#MeToo movement will fail.

This requires new forms of collaboration and coalition-building. Legacy civil rights organizations must prioritize sexual assault and domestic violence with the same passion that they bring to voting rights or criminal justice reform. White feminists should organize for equal pay and reproductive rights around an anti-racist framework. Victims’-rights organizations must offer culturally specific resources and lift up the work of organizations led by black women that have long been on the front line of these issues like Black Women’s Blueprint, Girls for Gender Equity, Love With Accountability, Project Nia and the Sasha Center.

With each passing day, more young women accuse R. Kelly of sexual assault. That means more people and institutions — with the glaring exception of his label, RCA — are taking their voices and by extension, girls who look like them, seriously. We’ve been waiting for this moment for a long time. Let’s not squander it.