Still, Atlanta’s black communities experienced certain graces in terms of economic prosperity. The strength of the city’s black merchant class, clustered along Auburn Avenue and Hunter Street, rested on the rigid system of segregation imposed by white politicians and supported by the white business elite.

Meanwhile, state constitutional conventions across the south delighted in the Jim Crow laws, including Georgia’s disenfranchisement of black voters and the enactment of the “all-white primary”. On September 1906, tensions in Atlanta boiled over, causing the most violent race riot witnessed for decades.

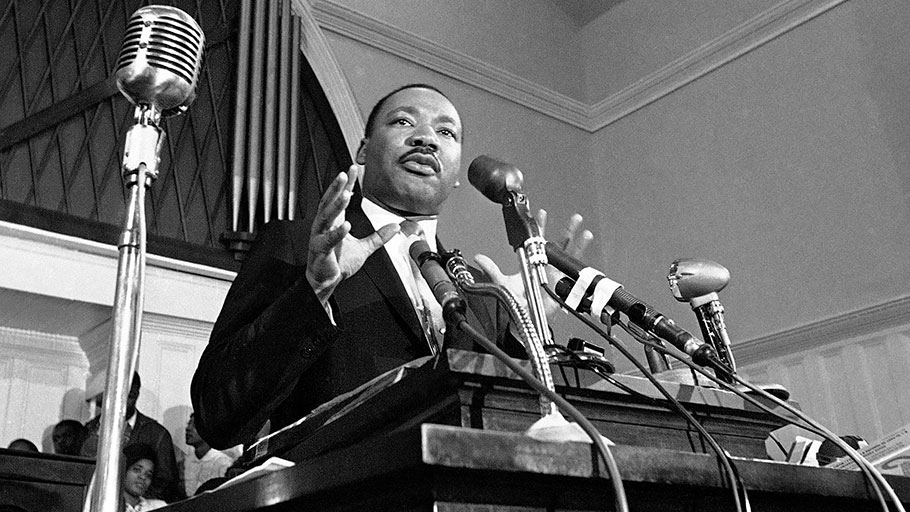

Atlanta’s most beloved son

Despite the riots, and right up until the civil rights legislation of the 1960s, Atlanta’s new black political elite insisted on moderation and incrementalism. In 1946, when the King v Chapman court case struck down the all-white Georgia primary, the black upper- and middle-class kingmakers asserted their might: John Wesley Dobbs and AT Walden founded the Atlanta Negro Voters League, which brokered a black political agenda and picked white political candidates without consulting the needs of Atlanta’s black working classes.

The schism between the black upper classes and the black poor had always riven Atlanta’s social fabric, but in the wake of Martin Luther King’s assassination it grew too wide to hold. In 1973, Atlanta’s black communities, along with an unprecedented coalition of white progressives, elected Maynard Holbrook Jackson as the city’s first black mayor.

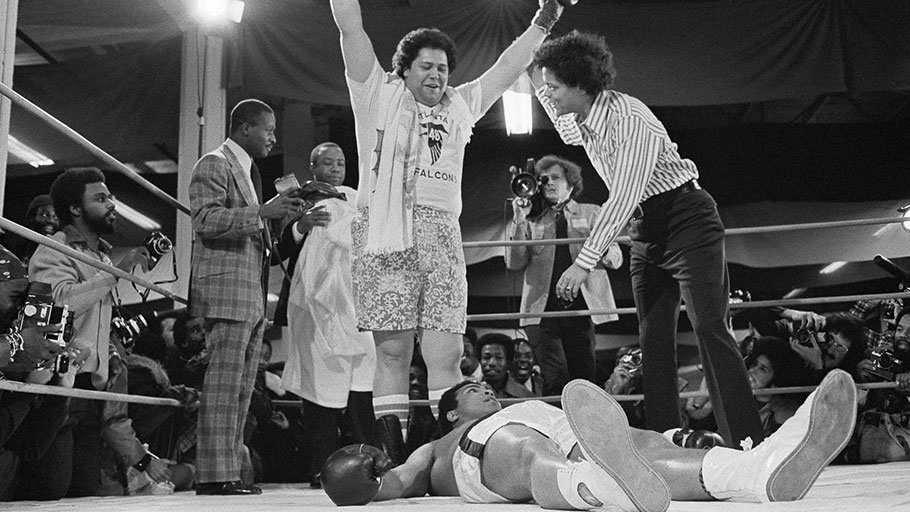

Maynard Jackson knocks out Muhammed Ali (1975). Photo: AP/Tom Hill/WireImage

Maynard Jackson meets Lynyrd Skynyrd (1977) Photo: AP/Tom Hill/WireImage

Maynard Jackson in 1981 posing with reward money offered for information on the Atlanta child murders. Photo: AP/Tom Hill/WireImage

Jackson’s election, a watershed moment for southern black political empowerment, gave new meaning to the city’s black mecca status. His affirmative action policies became the gold standard for American industry, producing an abundance of black millionaires, buttressed by the expansion of Atlanta’s airport and public transportation.

But economic inclusion was not his only significant contribution to modern civil rights. Both crime and police brutality subsided during Jackson’s first term, and his creation of the Neighborhood Planning Unit allowed black communities to have some say in the city’s development of their communities – what we would now describe as preventing displacement through gentrification.

His second term was less successful, tarnished by the so-called Atlanta child murders, in which a series of poor black children – and several adults – were killed, their bodies left in fields and deserted areas. Popular sentiment turned against Jackson, who began to gain the reputation of someone more interested in protecting the black mecca image than in protecting black people themselves.

Rise of a global city

The 1980s ushered in Atlanta’s second black mayor, Andrew Young, who had cut his teeth as one of King’s trusted lieutenants and was a former UN ambassador. Under Young, Atlanta gained a new reputation – as a global city with international black citizenship.

Yet Young’s tenure as the city’s mayor was tainted by numerous social ills and a pernicious financial crisis. The demise of industrialization and the rise of the information age left Atlanta’s black working classes and poor mired in unemployment. Reaganomics betrayed Atlanta’s black communities on issues of education and fair housing, while the emergence of crack cocaine systematized the War on Drugs – a war focused mostly on black and brown people – and diverted subsidies from education into incarceration. The prison-industrial complex and the militarization of the police reached new heights. And the arrival of Aids was a paralyzing blow, with Atlanta’s black populations suffering some of the highest rates of HIV in the world.

It was in this context that Atlanta bid for the 1996 Olympics.

The opening ceremony of the Atlanta Olympic Games in 1996. Photograph: Actionplus/Corbis via Getty Images

The bid was a full-scale invocation of King’s legacy, replete with all of the theatrics of the black church: homiletics and soul-stirring organ music, all to attract the world to King’s hometown, the poster child for race relations. But to Atlanta’s black rank-and-filechampioned by King during his lifetime, the Olympic bid was a vehicle to further criminalize, demonize, disfranchise and displace.

Hip-hop, racial politics and an Atlanta beyond boosterism

To the glossy Olympic City version of the black mecca story, the rise of hip-hop offered a sobering counter-narrative. The Dirty South movement arose out of the legacy of Atlanta culture fostered under black rule, and selected its subject matter from the daily lives of the black poor who suffered from the late 1970s to the mid-1990s. Atlanta artists such as OutKast and Goodie Mob expressly rejected that black mecca and Olympic City imagery; instead, they portrayed the experience of the working and poorer classes in Atlanta’s black ghettoes.

The music and lyrics of these artists reflected the inherent tensions within Atlanta’s black community, parts of which languished in poverty and despair and parts of which rose to new and unprecedented levels of prestige and wealth. The black nouveau riche, steeped in Atlanta’s black popular culture, shook the foundations of the existing elite; yet also became, in its own way, resistant to those who aspired to join.

Hip-hop duo OutKast circa 1990. Photograph: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Indeed, in recent years political participation in Atlanta has reached record lows. In the 2017 mayoral election, contested between Mary Norwood and Keisha Lance Bottoms, of 640,861 registered voters only 92,169 ballots were cast. The election was divided by race: maps show that Bottoms’ victory came from predominantly black neighborhoods in roughly Atlanta’s southern half; Norwood broadly took the north.

Atlanta needs a new story – something that reflects its true importance to the idea of race relations in the American south. Today Georgia and the city of Atlanta in particular have an opportunity to make history by electing the nation’s first blackfemale governor. While the US president discriminates against women and people of colour, Atlanta has in its grasp the power to truly make America great by embracing democracy, freedom and inclusivity – to trump the hubris of boosterism and start a new and more honest chapter in the story of the American south.

Maurice J Hobson is an associate professor of African American studies at Georgia State University and the author of books including The Legend of the Black Mecca: Politics and Class in the Making of Modern Atlanta.