The Black Press USA is the Web site of the National Newspaper Publishers Association (NNPA), an umbrella grouping of over 200 African-American newspapers spread across the USA.

The NNPA has launched a global news feature series on the history, contemporary realities and implications of the transatlantic slave trade.

Read the entire series below:

- Part I. UN Observes International Remembrance of Slave Trade

- Part II. The Catholic Church Played Major Role in Slavery

- Part II. A Five Hundred Year-Old Shared History

- Part IV. The Economic Engine of the New Nation

- Part V. Five Hundred Years Later, Are we still Slaves?

The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Part I

UN Observes International Remembrance of Slave Trade

By Stacy M. Brown, NNPA Newswire Correspondent—

“The fact that slavery was underway for a century in South America before introduction in North America is not widely taught nor commonly understood…”

A people without the knowledge of their past history, origin and culture

is like a tree without roots — Marcus Garvey

Washington, DC, August 23, 2018 — The National Newspaper Publishers Association (NNPA) announces the launch of a global news feature series on the history, contemporary realities and implications of the transatlantic slave trade, according to NNPA President and CEO, Dr. Benjamin F. Chavis Jr.

The night of Aug. 22 to Aug. 23, 1791, in Santo Domingo – today Haiti and the Dominican Republic – saw the beginning of the uprising that would play a crucial role in the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade.

The slave rebellion in the area weakened the Caribbean colonial system, sparking an uprising that led to abolishing slavery and giving the island its independence.

It also marked the beginning of the destruction of the slavery system, the slave trade and colonialism.

Each year, on Aug. 23, the United Nations hosts an International Day for the Remembrance of the Slave Trade and its Abolition to remind the world of the tragedy of the transatlantic slave trade.

U.N. officials said it provides an opportunity to think about the historic causes, the methods, and the consequences of slave trade.

Experts said it’s important to never forget.

And, with the approaching 500th anniversary of the date Africans were first forced into slavery in America, many like Felicia M. Davis, the director of the HBCU Green Fund, which invests in sustainable campus solutions for historically black colleges and universities, said she believes African enslavement demands reexamination.

“The fact that slavery was underway for a century in South America before introduction in North America is not widely taught nor commonly understood,” Davis said.

“It is a powerful historical fact missing from our understanding of slavery, its magnitude and global impact. Knowledge that slavery was underway for a century provides deep insight into how enslaved Africans adapted,” she said.

Far beyond the horrific “seasoning” description that others have provided, clearly generations had been born into slavery long before introduction in North America, Davis argued.

“It deepens the understanding of how vast majorities could be oppressed in such an extreme manner for such a long period of time. It is also a testament to the strength and drive among people of African descent to live free,” she said.

The history of the United States has often been described as the history of oppression and resistance to that oppression, said David B. Allison, the editor of the book, “Controversial Monuments and Memorials: A Guide for Community Leaders.”

Slavery and the resulting touchstones stemming from slavery throughout the history of the United States run as a consistent thread that illuminates the soul and essence of America, said Allison, a historian with a master’s degree in U.S. History from Indiana University-Purdue University at Indianapolis.’

“From the compromises and moral equivocation in the founding documents during the Revolutionary Era – statements like ‘All men are created equal’ were written by a man who kept Black men and women as decidedly unequal as slaves – to the Civil War and Civil Rights Movement, the tragedy and terror of slavery are fundamental to the history of the United States,” Allison said.

Today, the fallout from the events of Aug. 2017 in Charlottesville – brought about by a white supremacist rally and touched off the debate around the potential removal of a statute to a leader of the Confederacy – continue to weigh down the collective psyche of this nation, Allison continued.

“Moreover, the rise in police profiling and brutality of Black men and the resulting rates of incarceration for African Americans highlight the ongoing oppression that was initially born in the crucible of slavery,” he said.

Allison added that it’s “absolutely essential to understand and remember that 2019 is the 500th anniversary of slavery in the United States so that we can understand both how our country became how it is now and how we might envision a more just future for all citizens.”

Each year the UN invites people all over the world, including educators, students, and artists, to organize events that center on the theme of the international day of remembrance.

Theatre companies, cultural organizations, musicians, and artists take part on this day by expressing their resistance against slavery through performances that involve music, dance, and drama.

Educators promote the day by informing people about the historical events associated with slave trade, the consequences of slave trade, and to promote tolerance and human rights.

Many organizations, including youth associations, government agencies, and non-governmental organizations, actively take part in the event to educate society about the negative consequences of slave trade.

Here in America, many organizations, activists and scholars are focused on 2019 as the anniversary of the arrival of the first Africans to be enslaved in Jamestown and 160 years since the last slave ship arrived, Davis said.

Also, there’s a growing list of apologies for slavery from colleges and universities, local governments and corporations.

Efforts are underway by the HBCU Green Fund to organize a national convening under the theme “Sankofa Remix” with three tracks: past, present and future.

The goal is to examine history from an African American perspective, explore current impacts including backlash from the election of the first Black president, and crafting a vision that extends at least 100 years into the future that features presentations from artists, activists, technology, scholars and other creative energy.

“It is encouraging to know that Black Press USA is focused on this topic. It is our hope that plans are underway to cover activities throughout the entire year,” Davis said, noting that 2019 also marks the 100thanniversary of the Red Summer Race Riots.

“The UN Decade of African Descent 2015-2024 should also be highlighted as the Black Press USA leads this important examination of history,” she said.

“Interestingly, the first and last slave ships to arrive in the U.S. both arrived in August. The HBCU Green Fund is working to put together a calendar of dates and observances.

“We would love to work with Black Press USA to promote a year-long observance that helps to reinvigorate and support the important role that the Black press plays in the liberation of Black people across the globe.

“We would be honored to have Black Press USA as a Sankofa Remix partner organization and look forward to collaboration opportunities,” Davis said.

The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Part II

The Catholic Church Played Major Role in Slavery

By Stacy M. Brown,NNPA Newswire Contributor —

The universal church taught that slavery enjoyed the sanction of Scripture and natural law.

“When the missionaries arrived, the Africans had the land and the missionaries had the Bible. They taught us how to pray with our eyes closed. When we opened them, they had the land and we had the Bible.” — Jomo Kenyatta, First President of Kenya, Africa

Washington, D.C.- September 4, 2018 – The Catholic Church played a vital role in the trans-Atlantic slave trade, according to historians and several published thesiis on the topic.

The trans-Atlantic slave trade was introduced by the coming of the Europeans who came with the Bible in the same manner that Arab raiders and traders from the Middle East and North Africa introduced Islam through the Trans-Saharan slave trade, according to AfricaW.com, a premiere informational website available throughout the continent.

“In fact, the Church was the backbone of the slave trade,” the authors wrote. “In other words, most of the slave traders and slave ship captains were very ‘good’ Christians.”

For example, Sir John Hawkins, the first slave-ship captain to bring African slaves to the Americas, was a religious man who insisted that his crew “serve God daily” and “love one another.” His ship, ironically called “The Good Ship Jesus,” left the shores of his native England for Africa in October 1562. Some historians argue that if churches had used their power, the Atlantic slave trade might have never occurred.

By the same logic, others argue that the Catholic church and Catholic missionaries could have also helped to prevent the colonization and brutality of colonialism in Africa. However, according to a 2015 Global Black History report, the Catholic church did not oppose the institution of slavery until the practice had already become infamous in most parts of the world.

In most cases, the churches and church leaders did not condemn slavery until the 17th century.

The five major countries that dominated slavery and the slave trade in the New World were either Catholic, or still retained strong Catholic influences including: Spain, Portugal, France, and England, and the Netherlands.

“Persons who considered themselves to be Christian played a major role in upholding and justifying the enslavement of Africans,” said Dr. Jonathan Chism, an assistant professor of history at the University of Houston-Downtown.

“Many European ‘Christian’ slavers perceived the Africans they encountered as irreligious and uncivilized persons. They justified slavery by rationalizing that they were Christianizing and civilizing their African captors. They were driven by missionary motives and impulses,” Chism said.

Further, many Anglo-Christians defended slavery using the Bible. For example, white Christian apologists for slavery argued that the curse of Ham in Genesis Chapter 9 and verses 20 to 25 provided a biblical rationale for the enslavement of Blacks, Chism said.

In this passage, Noah cursed Canaan and his descendants arguing that Ham would be “the lowest of slaves among his brothers” because he saw the nakedness of his father. A further understanding of the passage also revealed that while some have attempted to justify their prejudice by claiming that God cursed the black race, no such curse is recorded in the Bible.

That oft-cited verse says nothing whatsoever about skin color.

Also, it should be noted that Black race evidently descended from a brother of Canaan named Cush. Canaan’s descendants were evidently light-skinned – not black. “Truly nothing in the biblical account identifies Ham, the descendant of Canaan, with Africans. Yet, Christian apologists determined that Africans were the descents of Ham,” Chism said.

Nevertheless, at the beginning the sixteenth century, the racial interpretation of Noah’s curse became commonplace, he said.

In 2016, Georgetown University in Washington, D.C. offered a public apology after acknowledging that 188 years prior, Jesuit priests sold 272 slaves to save the school from financial ruin.

This is how The New York Times first reported the story: The human cargo was loaded on ships at a bustling wharf in the nation’s capital, destined for the plantations of the Deep South. Some slaves pleaded for rosaries as they were rounded up, praying for deliverance.But on that day, in the fall of 1838, no one was spared: not the 2-month-old baby and her mother, not the field hands, not the shoemaker and not Cornelius Hawkins, who was about 13 years old when he was forced onboard.

Their panic and desperation would be mostly forgotten for more than a century. But this was no ordinary slave sale. The enslaved African-Americans had belonged to the nation’s most prominent Jesuit priests. And they were sold, along with scores of others, to help secure the future of the premier Catholic institution of higher learning at the time, known today as Georgetown University.

“The Society of Jesus, who helped to establish Georgetown University and whose leaders enslaved and mercilessly sold your ancestors, stands before you to say that we have greatly sinned,” Rev. Timothy Kesicki, S.J., president of the Jesuit Conference of Canada and the United States, said during a Liturgy of Remembrance, Contrition, and Hope.

“We pray with you today because we have greatly sinned and because we are profoundly sorry.”

During the early republic, Catholics celebrated the new Constitution for its guarantee of religious liberty while simply accepting its guarantee of slaveholding, according to Blackthen.com.

Internal church politics mattered too. When the Jesuit order was suppressed in 1773, the plantation system of the order in Maryland was seen as a protection for their identity and solidarity.

The universal church taught that slavery enjoyed the sanction of Scripture and natural law. Throughout the antebellum period, many churches in the South committed to sharing their version of the Christian faith with Blacks. They believed that their version of Christianity would help them to be “good slaves” and not challenge the slave system, Chism said.

“Yet, it is important to note that African Americans made Christianity their own, and Black Christians such as Nat Turner employed Christian thought and biblical texts to resist the slave system. Furthermore, Black and white abolitionist Christians played a major role in overturning the system of slavery,” he said.

The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Part III

A Five Hundred Year-Old Shared History

By Stacy M. Brown,NNPA Newswire Contributor —

“It started with slave ships… There are more records of slave ships than one would dream. It seems inconceivable until you reflect that for 200 years ships sailed carrying cargo of slaves. How can man be nonviolent… in the face of the… violence that we’ve been experiencing for the past (500) years is actually doing our people a disservice in fact, it’s a crime, it’s a crime.” — Public Enemy- “Can’t Truss It.”

The transatlantic slave trade is often regarded as the first system of globalization and lasted from the 16th century through much of the 19th century. Slavery, and the global political, socio-economic and banking systems that supported it, constitutes one of the greatest tragedies in the history of humanity both in terms of scale and duration.

The transatlantic slave trade was the largest mass deportation of humans in history and a determining factor in the world economy of the 18th century where millions of Africans were torn from their homes, deported to the American continent and sold as slaves, according to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization – or UNESCO.

The transatlantic slave trade that began about 500 years ago connected the economies of three continents with Spain, Portugal, the Netherlands, England and France acting as the primary trading countries.

“The transatlantic slave trade transformed the Americas,” wrote Dr. Alan Rice, a Reader in American Cultural Studies at the University of Central Lancashire in Preston in the United Kingdom.

“Three factors combined to cause this transformation. Large amounts of land had been seized from Native Americans and were not being used,” Rice said. “Europeans were looking for somewhere to invest their money and very cheap labor was available in the form of enslaved Africans [thus] the Americas became a booming new economy.”

The transatlantic slave trade also formed an essential bridge between Europe’s New World and its Asia trade and, as such, it was a crucial element in the development of the global economy in the 18th century, Professor Robert Harms wrote for Yale University’s “Global Yale.”

Harms, a professor of History at Yale and chair of the Council on African Studies continued:

“There was one basic economic fact – little noticed by historians – that provides the key to the relationship between the direct trade and the circuit trade.

“When a French ship arrived in the New World with a load of slaves to be bartered for sugar, the value of the slaves equaled about twice as much sugar as the ship could carry back to France. For that reason, the most common form of slave contract called for fifty percent of the sugar to be delivered immediately and the remainder to be delivered a year later.

“The second delivery carried no interest penalty, and so the slave sellers were in effect giving the buyers an interest-free loan.”

In total, UNESCO estimates that between 25 to 30 million people — men, women and children — were deported from their homes and sold as slaves in the different slave trading systems.

More than half – 17 million – were deported and sold during the transatlantic slave trade, a figure that UNESCO historians said doesn’t include those who died aboard the ships and during the course of wars and raids connected to the slave.

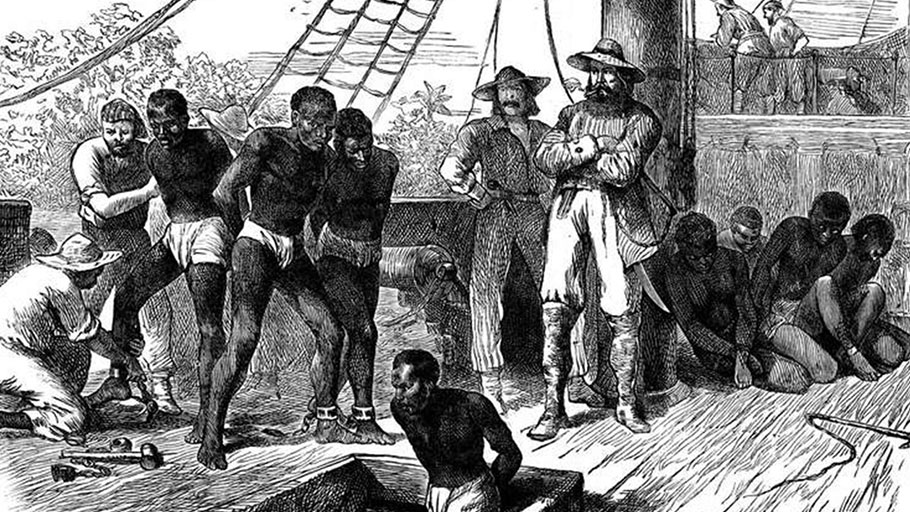

The trade proceeded in three steps. The ships left Western Europe for Africa loaded with goods which were to be exchanged for slaves.

Upon their arrival in Africa, the captains traded their merchandise for captive slaves. Weapons and gun powder were the most important commodities but textiles, pearls and other manufactured goods, as well as rum, were also in high demand.

The exchange could last from one week to several months.

The second step was the crossing of the Atlantic. Africans were transported to America to be sold throughout the continent.

The third step connected America to Europe.

The slave traders brought back mostly agricultural products, produced by the slaves. The main product was sugar, followed by cotton, coffee, tobacco and rice.

The circuit lasted approximately eighteen months and, in order to be able to transport the maximum number of slaves, the ship’s steerage was frequently removed, historians said.

Many researchers are convinced that the slave trade had more to do with economics than racism. “Slavery was not born of racism, rather racism was the consequence of slavery,” historian Eric Williams wrote in his study, “Capitalism & Slavery.”

“Unfree labor in the New World was brown, white, black, and yellow; Catholic, Protestant, and pagan. The origin of Negro slavery? The reason was economic, not racial, it had to do not with the color of the laborer, but the cheapness of the labor,” Williams said.

Also, contrary to “the popular portrayal of African slaves as primitive, ignorant and stupid, the reality is that not only were Africans skilled laborers, they were also experts in tropical agriculture,” said editor and social media and communications expert, Michael Roberts.

In a dissertation for op-ed news earlier this year, Roberts said, Africans were well-suited for plantation agriculture in the Caribbean and South America.

Also, the high immunity of Africans to malaria and yellow fever, compared to white Europeans and the indigenous peoples of the Caribbean and South America, meant Africans were more suitable for tropical labor.

“While Native Americans’ labor were initially used, Africans were the final solution to the acute labor problem in the New World,” Roberts said.

“The slave trade was one of the most important business enterprises of the 17th century. The undisputed fact is that the nation states of Europe stabilized themselves and developed their economies mainly at the expense of millions of Black African people,” he said.

During the 16th Century, when Europeans first made regular contact, West Africa had highly developed civilizations and Africans were keen to trade their gold, silver, copper, Ivory and spices for European pots, pans, cloth and guns.

However, Europeans soon became more interested in exploiting the people of Africa and forcing them into slave labor.

Most of the slaves were taken from the West coast, but some were kidnapped further inland from the interior.

“The biggest lesson to be learned from this dark and evil chapter in human history is that exploiting fellow humans for cheap labor never pays off in the long run,” said Pablo Solomon, an internationally recognized artist and designer who’s been featured in 29 books and in newspapers, magazines, television, radio and film.

“The acts of using fellow humans as beasts of burden to save a few bucks always ends up costing more in the long run both in real money and in societal decay,” Solomon said.

“Any rationalization of misusing fellow humans is both evil and ignorant,” he said.

One aspect of the transatlantic slave trade that would greatly enhance its understanding is that the English began to enslave and export Irish persons to the Caribbean in the time of Oliver Cromwell, said Heather Miller, an educator and writer with expertise in the teaching of reading and writing, who holds graduate degrees from Harvard and MIT.

Cromwell was known for his campaign in Ireland that centered on ethnic cleansing and the transportation of slave labor to the Barbados.

“Irish enslaved persons worked alongside African enslaved persons in the Caribbean,” Miller said.

However, historians generally agree that the most cruel and exploitative people have been the African.

“From the moment when Europeans took their slaves from a race different from their own, which many of them considered inferior to other human races, and assimilation with whom they all regarded with horror, they assumed that slavery would be eternal,” historian Winthrop D. Jordan wrote in his dissertation, “White Over Black: American Attitudes Toward the Negro.”

“From the moment when Europeans took their slaves from a race different from their own, which many of them considered inferior to other human races, and assimilation with whom they all regarded with horror, they assumed that slavery would be eternal,” historian Winthrop D. Jordan wrote in his dissertation, “White Over Black: American Attitudes Toward the Negro.”

While tribal leaders assisted in the capturing of some African slaves, its without any doubt that foreigners were overwhelming the most egregious in their pursuit of men, women and children who would be placed in the horrors of forced labor and inhumane treatment.

The transatlantic slave trade would become the largest forced migration in history.

It started at the beginning of the sixteenth century and, until the mid-17th century, Spanish America and Portuguese Brazil were the major slave markets for European slave traders.

The Dutch participation in the transatlantic slave trade started in the 1630s and ended at the beginning of the nineteenth century, according to Henk den Heijer, professor emeritus in Maritime History at the Leiden University in the Netherlands.

During that period, the Dutch shipped 600,000 Africans to the colonies in the New World.

“Initially, the Dutch were against slavery which was considered to be a catholic heresy. This antislavery point of view can be easily explained,” den Heijer said.

“Dutch seafarers first ventured across the Atlantic without the intention of enslaving anyone. They were mainly interested in the trade in Atlantic products like salt, sugar, wax and dye wood. At the beginning of the 17th century, however, the Dutch established small plantation colonies on the coast of Guyana, the area between the Orinoco and Amazon rivers,” he said.

“Most of the early settlements were populated with Dutch colonists and a few indigenous slaves. The Dutch embraced the slave trade and slavery on a large scale for the first time in Brazil.”

The slave trade also brought a great deal of wealth to the British ports that were involved.

Researchers noted the count of slaves and slave ships that came through the main British ports in 1771, when the average working person earned $35 in British currency per year and a single slave in good condition could be sold in the Caribbean for $25.

Liverpool had 107 ships and transported 29,250 slaves, historians noted.

London had 58 ships carrying 8,136 slaves while Bristol had 23 ships that transported 8,810 slaves.

Additionally, researchers said Lancaster had 4 ships that transported 950 slaves.

From 1791 to 1807, British ships carried 52 percent of all slaves taken from Africa while, from 1791 to 1800, British ships delivered 398,719 slaves to the Americas.

While it was the British who stood as the most progressive couriers of whatever was transported through the sea, many other countries chartered ships and descended upon African nations to capture slaves.

Ships sailed to Africa loaded with guns, tools, textiles and other manufactured goods and crews with guns went ashore to capture slaves and purchase slaves from tribal leaders.

Slave ships spent months travelling to different parts of the coast, according to historians who described the devastation on a webpage titled The Transatlantic Slave Trade.

Captives were often in poor health from the physical and mental abuse they suffered.

The air in the hold was foul and putrid, according to historians.

From the lack of sanitation, there was a constant threat of disease. Epidemics of fever, dysentery and smallpox were frequent. Captives endured these conditions for months. In good weather the captives were brought on deck in midmorning and forced to exercise.

They were fed twice a day and those refusing to eat were force-fed.

Those who died were thrown overboard. The combination of disease, inadequate food, rebellion and punishment took a heavy toll on captives and crew.

Surviving records suggest that until the 1750s, one in five Africans on board ship died.

At least two million Africans – 10 to 15 percent – died during the infamous “Middle Passage” across the Atlantic.

Some European governments, such as the British and French, introduced laws to control conditions on board. They reduced the numbers of people allowed on board and required a surgeon to be carried.

The principal reason for taking action was concern for the crew, not the captives, historians said.

The surgeons, often unqualified, were paid head-money to keep captives alive. By about 1800 records show that the number of Africans who died had declined to about one in 18.

When enslaved Africans arrived in the Americas, they were often alone, separated from their family and community, unable to communicate with those around them.

“When we arrived, many merchants and planters came on board and examined us. We were then taken to the merchant’s yard, where we were all pent up together like sheep in a fold,” according to a published description from “The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano.”

“On a signal the buyers rushed forward and chose those slaves they liked best.”

Sold, branded and issued with a new name, the enslaved Africans were separated and stripped of their identity.

In a deliberate process, meant to break their will power and make them totally passive and subservient, the enslaved Africans were “seasoned,” which meant that, for a period of two to three years, they were trained to endure their work and conditions – obey or receive the lash.

It was mental and physical torture.

“The anniversary of the Transatlantic Slave Trade needs to be marked in some way, not celebrated, but recognized and memorialized because of the effects this decision had then that still affects the world today,” said Dr. Jannette Dates, dean emerita at the School of Communications at Howard University in Washington, D.C.

“The Black Press continues to play its historic role in keeping issues of significance to African Americans in the forefront for black people’s awareness, knowledge and better understanding of our history,” Dr. Dates said.

The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Part IV

The Economic Engine of the New Nation

By Stacy M. Brown,NNPA Newswire Contributor —

“And America, too, is a delusion, the grandest one of all. The white race believes – believes with all its heart – that it is their right to take the land. To kill. Make war. Enslave their brothers. This nation shouldn’t exist, if there is any justice in the world, for its foundations are murder, theft, and cruelty. Yet here we are.” ― Colson Whitehead, The Underground Railroad

Once they reached the Americas, enslaved Africans were sold to the highest bidder at slave auctions and, once they had been purchased, slaves worked for nothing on plantations without any rights at all.

Often punished harshly, some slaves committed suicide, according to historians and pregnant women – many impregnated by their white slave masters – preferred abortion.

The historic accounts of the transatlantic slave trade, only worsen as they’re told.

From the earliest stages of the transatlantic slave trade 500 years ago and throughout that most ignominious period, many enslaved Africans tried to reduce the pace of their work by pretending to be ill, causing fires and by breaking tools, according to historians.

Though few were able to escape, most who attempted to flee were caught and beaten and some even murdered.

“Slavery is one of the foundational pillars of American society, propping up the nation starting in the earliest days of the Republic and touching the lives of everyone in America,” said Hasan Jeffries, a history professor at Ohio State University.

“And, its legacy has been long lasting,” said Jeffries who specializes in African American history and contemporary black history, which includes the institution of slavery and its effect on African Americans in the United States from the founding era through the Civil Rights movement and today.

“The deeply rooted belief in white supremacy that justified slavery survived its abolition in 1865 and undergird the new systems of African American labor exploitation and social control, namely Jim Crow, that sought to replace what had been lost as a result of emancipation,” Jeffries continued.

“Slavery may have ended in 1865, but a slaveholder mentality persisted, shaping the contours of American life for decades to come. This legacy of slavery is very much what African Americans have been fighting against from the moment of emancipation through the present.”

James Madison’s Montpelier, the home of the Father of the Constitution, an institution that examines slavery during the Founding Era and its impact today, recently commissioned a study that examined how Americans perceive their Constitutional rights.

Research found that African Americans (65 percent) are less likely than whites (82 percent) to believe that their Constitutional rights are regularly upheld and respected.

The study also revealed that African Americans (62 percent) are more likely than whites (36 percent) to believe that civil rights is the most important Constitutional issue to the nation; findings that make it clear that race continues to play a major role in determining how Americans perceive Constitutional rights.

“Enslaved people were considered property during the Founding Era, therefore the Constitution’s declarations of ‘we the people’ and ‘justice’ excluded them, protecting one of the most oppressive institutions in history,” said Kat Imhoff, president and CEO of James Madison’s Montpelier.

“While the words ‘slave’ and, or, ‘slavery’ are never mentioned in the Constitution, they are referenced and codified in a variety of ways throughout the document,” Imhoff said.

“The founders compromised morality – many were recorded as being opposed to slavery, but on the other hand many were not – and power – in some cases, states bowed to slaveholding counterparts to ensure the Constitution would be ratified in the name of economics,” she said.

Imhoff continued:

“Slavery, when all was said and done, was incredibly profitable for white Americans – and not just in the South. It was the economic engine of the new nation. While Madison and his ideas remain powerful and relevant, they also stand in stark contrast to the captivity and abuse of Madison’s own slaves. At Montpelier, on the very grounds where Madison conceived ideas of rights and freedom, there lived hundreds of people whose freedom he denied.”

Indeed, Madison’s story is one of the first in the continuing journey of Americans who struggled to throw off bonds of oppression and exercise the fullness of what it means to be free, Imhoff added.

Working at James Madison’s Montpelier provides Imhoff and others a view of race and slavery’s legacy through the eyes of those who descended directly from the enslaved individuals who lived at Montpelier and other estates in the nearby Virginia area.

“As a leader of this cultural institution engaged in the interpretation of slavery, I believe to truly move forward, it is essential to engage the descendants to help us interpret slavery in real terms and illuminate their ancestors’ stories,” Imhoff said.

“Our country continues to grapple with the effects of slavery. Some of us feel it in deeply personal ways. Others only know of it historically or academically, as part of the distant, long-ago past.

“These differences make it all the more important to engage in worthwhile discussions with each other. We must have a more holistic conversation about freedom, equality and justice, and ensure we are inclusive of those people who it affects most readily.”

The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Part V

Five Hundred Years Later, Are we still Slaves?

By Stacy M. Brown, NNPA Newswire Correspondent—

“I prefer to be true to myself, even at the hazard of incurring the ridicule of others. Rather than to be false, and to incur my own abhorrence.” — Frederick Douglass

“Ignorance is the greatest slave master in the universe… The greatest prison anyone can escape from is ignorance.” — Matshona Dhliwayo

“These negroes aren’t asking for no nation. They wanna crawl back on the plantation.” — Malcolm X

Five Centuries ago – on August 18, 1518 to be exact – the King of Spain, Charles I, issued a charter authorizing the transportation of slaves direct from Africa to the Americas, according to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, or UNESCO.

Five hundred years later, the devastating effects remain.

Some argue, however, that slavery continues to exist – in that far too many African Americans possess a slave’s mentality. Books on the topic are a plenty.

Harvard psychiatrist Alvin Poussaint wrote extensively about the high suicide rates among black males which doubled over a 15-year period beginning in 1980. “African-American young men may see the afterlife as a better place,” Poussaint wrote in his book, “Lay My Burden Down: Suicide and the Mental Health Crisis among African-Americans.”

In her book, “Black Pain: It Just Looks Like We’re Not Hurting,” famed author and social worker, Terrie M. Williams, writes about the “high toll of hiding the pain associated with the black experience” on mental health.

Portland State University scholar Joy DeGruy also tried explaining the slave mentality in her controversial theory, “Post-Traumatic Slave Syndrome.”

The Urban Dictionary and other works says that a slave mentality is one of feeling inferior or of feeling lost without hope, a feeling that we do not have the power to significantly alter our own circumstances.

“Another sad symptom of having a slave mentality is believing that white people are superior,” writes Kuuleme T. Stephens noted in her blog. “A person conditioned to quietly, and without objection, accept harmful circumstances for themselves as the natural order of things. …They’re also conditioned to accept their master’s view and beliefs, about themselves, and strive to get others, within their group, to accept their master’s view.

“I often hear people make the claim that blacks were better off when they were slaves. I myself have been known to say such things when people piss me off and respond out of ignorance to a posting or article. My reason for making such an argument is if black Americans are not going to stop living in the past and blaming other for their problems, we will never move forward as a people. …To maintain a belief that you are owed something and entitled to things when you are doing nothing to help yourself is absurd.

“To stay ignorant as a lifestyle choice and have others (the government) take care of you and tell you what to do is exactly what the slaves did, and some continued to do even after they were freed. …My great grandmother, whose father and grandfather were slaves, has a slavery mentality because they were raised by slaves and their opinions and beliefs were passed down as such.”

Even now, millions of Americans of recognizably African descent languish in societal backwaters, according to historians and experts on slavery. And, the dichotomy that exists between those who view living in America as a struggle to survive and those that see it as a land of opportunity has driven a wedge between many in the African American community.

“We’re absolutely still slaves today,” said Sean XG Mitchell, a Hip-Hop activist and author of several books on the black experience, including “The African American Spiritual Practice of Seven.”

“We’re the only race of people who do not have a cultural orientation regarding our identity. Every powerful and successful race and/or ethnic group of people have an orientation that centers around language, education, religion, names and customs which is where their unity, self-respect, pride and dignity-the prerequisite of power- comes from,” he said.

As a result of slavery, African Americans do not have a cultural orientation that centers around their historical experience as a people. “We see the outcome in the deficiency of our social and economic development. To a certain extent, we’ve been fighting racism and injustice all wrong which is why it’s been an ongoing issue for over [500] years. Real empowerment comes from culture and until we understand and embrace what it means to be an African people will always be slaves,” Mitchell said.

“I believe there is a dividing legacy of slavery that have pitted certain segments of the black community against each other,” Mitchell continues. “We have an obvious color barrier between light skin and dark skin, creating somewhat of a caste system that gives privilege to the lighter shade in most cases whether we’re referring to employment opportunities or relationships.

“It’s all a fallout of slavery because slaves often were pitted against each other as a means of preventing unity.”

During slavery, the dark-skinned blacks worked in the fields while light-skinned blacks worked in the house, hence the terms “field Negroes” and “house Negroes.”

“It got so bad, that not only did the slave owner, who was often responsible for the lighter shade of brown his slaves had, give lighter-skinned blacks more respect, but so did the dark-skinned blacks,” blogger Jasmyne Cannick writes in an opinion column for NPR.

This was best illustrated in Spike Lee’s 1988 film “School Daze” in the scene set in a beauty salon between the “jiggaboos,” the darker-skinned blacks with “nappy” hair, and the “wannabes,” the lighter-skinned blacks with “straight” and often weaved hair.

“You know, I can’t think of one time that I witnessed or heard of white children taunting each other for being paler than the next, but I can think of numerous occasions where I have seen black children teasing each other for being ‘too black,’” Cannick said.

“And while our lighter skin shades can be attributed to the Massuh’s preference for his female black slaves over his own wife, we can’t blame the Massuh for us continuing to feed into the hype that light is good and dark is bad,” she said.

Post-slavery, post-Jim Crow, and post-Civil Rights, African Americans haven’t reached their full potential in part because of an acute lack of effort with too many wallowing in self-pity, say those who’ve argued against reparations.

Walter Williams, an economics professor at George Mason University in Washington, D.C. and an opponent of reparations, suggested that African-Americans have actually benefited from the legacy of slavery.

“Almost every black American’s income is higher as a result of being born in the United States than any country in Africa,” Williams, who is black, told ABC News.

“Most black Americans are middle-class,” Williams said, claiming that the U.S. has made “significant” investments in African Americans since the slave trade ended.

“The American people have spent $6.1 trillion in the name of fighting poverty,” he said. “We’ve had all kinds of programs trying to address the problems of discrimination. America has gone a long way.”

Countering that argument, others said America has continued to do a disservice to black Americans, prolifically using the criminal justice system as tool akin to slavery that almost assures a lifetime of dependency on taxpayers.

“My expertise is the criminal justice system, which has long been used to intimidate, oppress, and abuse African-Americans. While officially our laws today are color-blind, which is different from the time of slavery, as implemented and used they aren’t,” said Roy L. Steinheimer Jr., a professor of Law at Washington and Lee University in Virginia.

What about black on black crime?

According to an evidence brief from the Vera Institute of Justice, titled, “An Unjust Burden: The Disparate Treatment of Black Americans in the Criminal Justice System,” and a report from the Bureau of Justice Statistics found that most violence occurs between victims and offenders of the same race, regardless of race.

The rate of both black-on-black and white-on-white nonfatal violence declined 79 percent between 1993 and 2015. The number of homicides involving both a black victim and black perpetrator fell from 7,361 in 1991 to 2,570 in 2016.

The issue isn’t the crime, it’s the selective disproportionately harsher punishment and sentencing of African Americans.

“Some of the laws, such as those disenfranchising convicted felons, have their origin, if not in the immediate aftermath of the civil war, then in the era that saw the emergence of the KKK and white supremacy. They were clearly intended to keep African-Americans and likely, though to a lesser extent poor whites, from the ballot box,” Steinheimer said.

Meanwhile, some of the newer laws that have negatively affected African-Americans still appear to result from some underlying beliefs that go back to the times of slavery.

“Interestingly that thinking has survived even during times of mass migration, which is presumably indicative of how deep-seated it is in American culture and law,” the professor continued.

The “broad scope of the criminal justice system reinforces the wealth disparity between white and black by making those caught up in it ever poorer and serves to drive even some of the better-of people caught up in it into poverty,” Steinheimer said.

“The economic impact resulting from slavery therefore gets magnified and reinforced by our criminal justice system, which increasingly stacks fines and fees,” he said.

In a dissertation for the Brookings Institute, Glenn C. Loury wrote that the dream that race might someday become an insignificant category in our civic life now seems naively utopian.

In cities across the country, and in rural areas of the Old South, the situation of the black underclass and, increasingly, of the black lower working classes is bad and getting worse. Simply put, the playing field has never been level for black Americans and that has only worsened the mental health of the community. “No well-informed person denies this, though there is debate over what can and should be done about it,” Loury said.

“Nor do serious people deny that the crime, drug addiction, family breakdown, unemployment, poor school performance, welfare dependency, and general decay in these communities constitute a blight on our society virtually unrivaled in scale and severity by anything to be found elsewhere in the industrial West,” he said.

“Slavery is one of the foundational pillars of American society, propping up the nation starting in the earliest days of the Republic and touching the lives of everyone in America. And its legacy has been long lasting,” said Hasan Jeffries, a James Madison Montpelier historian and history professor at Ohio State University who specializes in contemporary black politics.

“The deeply rooted belief in white supremacy that justified slavery survived its abolition in 1865 and undergird the new systems of African American labor exploitation and social control, namely Jim Crow, that sought to replace what had been lost as a result of emancipation,” Jeffries said.

As a result, slavery has caused certain symptoms of dysfunction in the African community, which has been reinforced in each generation, according to historians at the African Holocaust Network.

The legacy of slavery has promoted and nursed the direct association between being African and being inferior. Being African and being unequal. Being African and being incapable and less worthy.

It also promotes ways of thinking which continue to impede growth and development, such as cultivating dependence and reactive behaviors, and more content to be at best an observer complaining about the world, instead of being a change agent in the world.

“The deterioration of the black American family is staggering,” Stephens said.

“If you ask a young black American what they want to be when they grow up, most will say they want to be a rapper/singer, football player, basketball player, or baseball player, and that is if they can tell you what they would like to be at all,” she said.

“No one tells them that only 0.03 percent make it to pro basketball, 0.08 percent make it pro football, and 0.45 percent make it pro baseball.

“We have a 40 percent dropout rate, for every 100,000 black men in the U.S., 4,777 are in prison or jail; for every 100,000 black American women, there are 743 in jail or prison, and 72 percent of black American women, and teens are unwed mothers.”

Historians at the James Madison Montpelier in Virginia said that it’s no accident that the U.S. Constitution opens with a message of inclusivity, establishing “justice” and ensuring “domestic tranquility” for the people.

However, it’s what that most famous preamble – and, indeed, the rest of the document – doesn’t address that’s more telling: The Constitution’s authors omit the vital distinction between their view of the differences between persons and property and, in doing so, ultimately protect one of history’s most oppressive institutions: Slavery.

About Stacy M. Brown — A Little About Me: I’m the co-author of Blind Faith: The Miraculous Journey of Lula Hardaway and her son, Stevie Wonder (Simon & Schuster) and Michael Jackson: The Man Behind The Mask, An Insider’s Account of the King of Pop (Select Books Publishing, Inc.) My work can often be found in the Washington Informer, Baltimore Times, Philadelphia Tribune, Pocono Record, the New York Post, and Black Press USA.