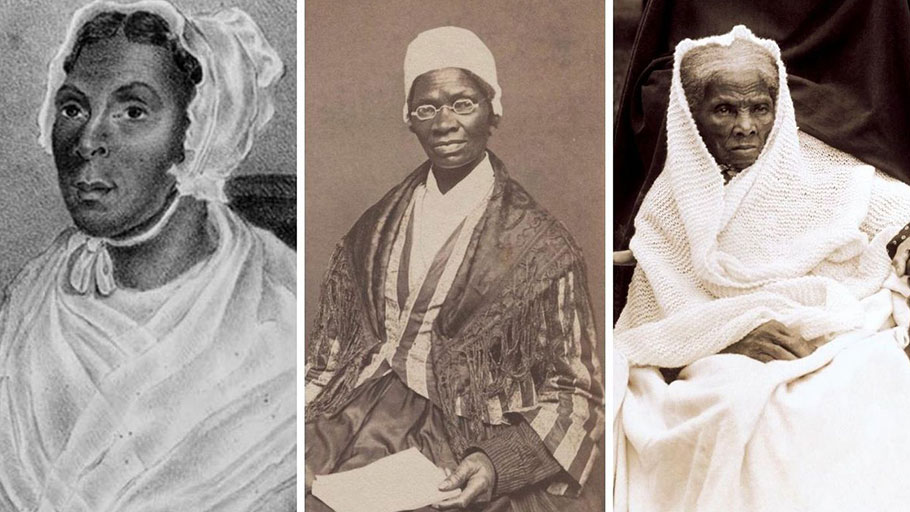

Jarena Lee, Sojourner Truth, and Harriet Tubman were pioneering Black women leaders who championed equality in the church, politics, civic rights, and other areas of public life.

While too many Black were disenfranchised even after the 19th Amendment’s ratification a century ago, they never waited for permission before promoting their vision of fundamental rights.

By Martha Jones, The Inquirer —

When it comes to 21st-century politics, Black women are our founders.

The double scourge of racism and sexism no longer defines American politics. The nomination of Sen. Kamala Harris to the Democrat’s VP slot, the more than 120 Black women running for seats in the House and the Senate, and the 90-plus percent who cast their ballots as a bloc, all announce that Black women have not only broken through — they have arrived. The American political imagination is no longer bound by more than two centuries of anti-Black and antiwoman thinking that had long relegated African American women to the margins.

In 2020, Black women in politics stand on the broad shoulders of the generations that came before. I call those generations the founders, because in the earliest decades of this nation, African American women pointed our way toward this current moment. Their shoulders were draped in shawls stitched from cotton and silk, worn by women who battled slavery and racism while also decrying sexism. While too many of them continued to be disenfranchised, even after many American women won the vote with the 19th Amendment ratified 100 years ago this month, Black women never waited for permission or formal authority before promoting their vision of fundamental rights.

In the earliest decades of the 19th century, Black women defined an ideal that we have been chasing for a very long time. They included these women who set a new bar in American politics and for our democracy:

Maria Miller Stewart took to the podiums of Boston in the 1830s to advise Americans that Black women were ready to lead. That they must. Stewart had been born into indentured servitude, but by the time she entered public life, she had been married, widowed, and was a teacher. She worried that in her adopted home of Boston, Black men were doing too little to combat the tide of racism that rose there despite slavery’s abolition there a half-century before. “O ye daughters of Africa, awake! awake! arise!” she urged. Black women, in Stewart’s view, were not destined to labor in kitchens or nurseries. They were ready to set aside the cruel mix of racism and sexism that plagued their lives, and lead.

Jarena Lee knew the pulpit was her destiny, and she aimed to convert those Christians who openly doubted that a Black woman could interpret and teach the Bible. Like Stewart, Lee came from humble beginnings. But by the 1810s, she was settled in Philadelphia and shared her gift for religious oratory with anyone who might listen. Lee traveled thousands of miles to bring new believers into her spiritual home, the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Reflecting on the opposition she faced, Lee later wrote: “Why should it be thought impossible, heterodox, or improper, for a woman to preach?” Lee urged American Christians to see beyond race and gender and into her soul, where she was certain God had authorized her work.

Sarah Mapps Douglass, another Philadelphian, wielded a pen to show Americans that Black women were destined to shape hearts and minds. Unlike Stewart and Lee, Douglass was born into a life of activism, a tradition she inherited from her parents, who were well-known for their politics and their philanthropy in Philadelphia. Douglass made her mark first as a correspondent to William Lloyd Garrison’s antislavery newspaper, the Liberator. She founded a Black women’s literary society, drafting its constitution and chairing its meetings. Douglass knew that she was rivaling men in her community who had for a long time steered public life. And she did not openly challenge them as Stewart and Lee had. Still, she laid a foundation for the founding of some of the earliest women’s antislavery societies in the United States. Douglass modeled how Black women were visionaries who expected to show the nation the way out of slavery and racism, all while challenging sexism.

“Black women were original, path breaking thinkers and activists telling anyone who would listen that neither racism nor sexism had a place in our democracy.”

These women, followed by a next generation that included Sojourner Truth and Harriet Tubman, set the bar high for this nation. They insisted that neither race nor sex should play any part in our collective lives, including politics. Black women alone carried this idea forward, as too many others refused to create a truly inclusive democracy. Still, their vision persisted across centuries, passed from generation to generation.

Nearly 100 years after Jarena Lee claimed her power at the pulpit, Black women suffragists in 1920 insisted on their right to the vote. It took an additional 45 years for them to secure the ballot for all with passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, and a full century for their vision to shape a major party’s national ticket with Harris’ nomination as the Democratic candidate for vice president.

Every grand ideal is rooted in a community of thinkers who see, out of their own circumstances, principles that will endure, principles that are timeless. In the earliest decades of this nation, Black women were among our founders who built those ideals. They were original, path-breaking thinkers and activists telling anyone who would listen that neither racism nor sexism had a place in our democracy. They exemplified that ideal in their own life’s work, set a high bar for everyone around them — and then waited for the nation to catch up. We are still not quite there yet, but we’re getting closer.

Source: The Inquirer

Martha S. Jones teaches history at Johns Hopkins University and is the author of Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All. @marthasjones_.