Part 1.

As we move from February, the month of the martyrdom of Nana Haji Malcolm X and into the month of March, I want to lift up his mother, Nana Louise Langdon Little (January 2, 1894 to December 15, 1989), womanist, activist intellectual, nationalist, pan-Africanist, organizer, freedom fighter, and mother, most notably of Haji Malcolm X. Indeed, she offered him and us all a model to emulate and a mirror by which we can measure ourselves as we make our way and work our will for good in the world. Thus, paraphrasing what Nana Ossie Davis said in his eulogy for Nana Louise’s martyred son, in honoring her we honor the best in ourselves. Hotep. Ase. Heri. Also, I do this for it is also moving from February, Black History Month I – the People Focus to March, Black History Month II – Women Focus. And there is an infinite number of lessons from the roles women perform in the making, molding and directing us and our history as persons and a people which are indispensable to our lives and liberation struggle.

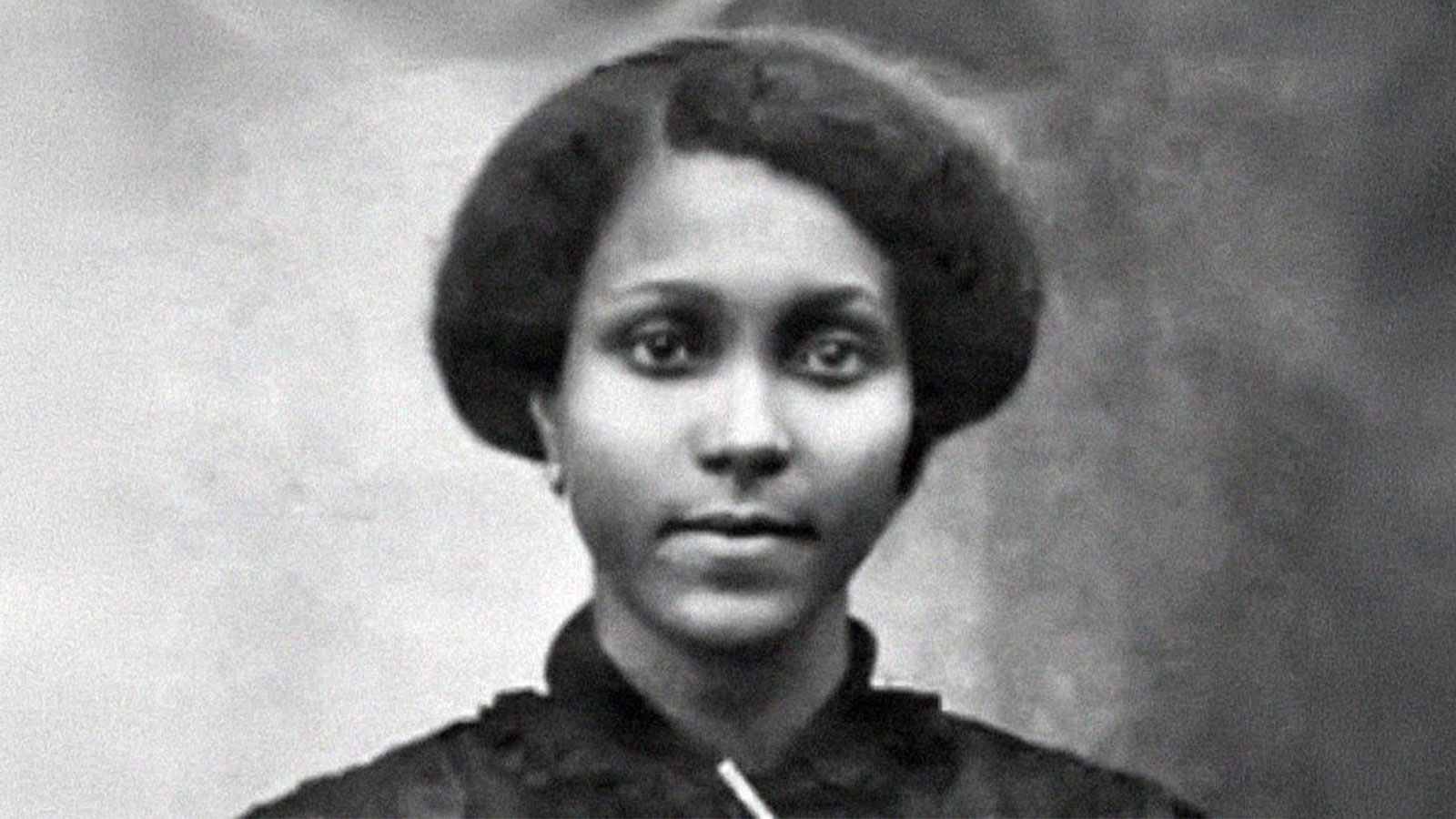

Louise Little, mother of Malcolm X

Now, as we lift up the life and legacy of Nana Louise Little, I want to use as my textual point of departure a quote attributed to her world-renowned and loving son, Haji Malcolm. He says, “The mother is the first teacher of the child. The message she gives that child, that child gives to the world”. And thus, in recognizing the world-encompassing significance of Haji Malcolm’s message to us and the world, it is best understood as a message that is rooted in and reflective of the message given to him by his beloved mother.

Therefore, I want to pay rightful homage to her, by calling Haji Malcolm’s message, not only his message to us and the world, but also a mother-son message given to the world. And it is a mother-son message in that her teachings in various forms are the foundation for his coming into being, developing and ultimately flourishing as the world historical teacher and leader he becomes. This in no way is a denial or diminishing of the fundamental role of his father, Nana Earl Little also in his moral and social formation but rather to strongly stress what has been under-stressed, i.e., the pivotal, and enduring role of Haji Malcolm’s mother in his formation and flourishing.

Although while he was in the Nation of Islam, Haji Malcolm always gave Messenger Elijah Muhammad and the NOI credit for what he had achieved and done, a more inclusive and accurate view would reveal an earlier and equally important grounding, i.e., that of his mother and father. Indeed, as Ilyasah Shabazz, daughter of Haji Malcolm and granddaughter of Nana Louise, states, “It was my Grandmother Louise and Rev. Little (her grandfather) who sowed the seeds of insight and discipline, educational values and organizational skills in my father… Mr. Muhammad cleared away the weeds and allowed these seeds to grow”. Moreover, even as Haji Malcolm is coming into consciousness as a Muslim, he relates its truths of life, religion and struggle to grounding with his mother. He says in a letter “We were taught Islam by Mom”, i.e., Islam as spirituality as distinct from organized religion, what the Muslims call a natural turning to the Divine. Moreover, he concludes that she was persecuted and institutionalized because “the devils knew she was not deadening our minds”, that is to say, teaching them servility and submission, but rather resistance. And he sums up his praise of his mother’s role in his intellectual and spiritual grounding and formation saying, “All of our achievements are Mom’s, for she was a most faithful servant of Truth years ago. All praise to Allah for her”.

Nana Louise Little taught Haji Malcolm and her children many interrelated lessons of life, work and struggle including: resistance and resilience: the discipline and love of learning: the self-appreciation, respect and responsibility of being Black; Pan-Africanism and a world-encompassing consciousness; and self-determination as a personal and political practice. And of all the lessons she taught, none is more important for us as persons and a people than resistance and resilience which she taught and demonstrated throughout her life. Furthermore, in talking of the central lesson of resistance and resilience which is a form of resistance itself, I want to stress the Kawaida conception of resistance which has three interrelated parts to it: opposition to oppression and oppressors, affirmation of the people and aspiration for an expansive conception of good in the world. Here, resistance presupposes and requires resilience. Indeed, to offer a daily and sustained radical refusal to be defeated, dispirited or diverted is not only an act of resistance, but is also an act of resilience, a defeat of the evil intentions of the oppressor to disable and destroy us in various ways.

Haji Malcolm declares his love for his mother and condemns society for turning her into an institutional statistic because of its “failure, hypocrisy, greed, and lack of mercy and compassion”. And he states in reflection on this and the oppression of Black people as a whole, “Hence I have no mercy or compassion in me for a society that will crush people, and then penalize them for not being able to stand up under the weight”. He speaks here especially of the institutionalization of his mother after the system crushes her under the weight of injustice and oppression, and then blames her for the problems they created for her. He does not recognize it until later, but not only does she teach him resistance in its fullest form, but also, she represents, even before he is born, a lived lesson of it.

It is, then, certainly a matter of great importance that Haji Malcolm begins his autobiography, his life’s story, with a narrative about his mother. It is a narrative of the love and courage of his mother while still pregnant with him. Going to the front door to confront the Klan that had come to attempt to silence his fearless and assertive father Nana Earl, Nana Louise gave Haji Malcolm a lesson in self-sacrificing love and courage while he was still in the womb. She does not hide or refuse to come to the door even though she is alone with the children. She defiantly refuses to be terrorized and pass that fear onto the children born and unborn.

Haji Malcolm and NOI Muslims often talked about how enslavers would impose spectacle forms of terrorizing vicious violence on Black men and the impact the mother’s trauma from this had on the unborn baby before it became a common medical understanding. He spoke of how “they made the pregnant Black women stand there and watch as they did it”, and how he believed that “all this grief and fear that they felt would go right into that baby, that Black baby that was yet to be born”. And he argued that it “would be born afraid, born with fear in it”.

But rejecting and resisting the evil intentions of the oppressor, Nana Louise became an unwavering shield for her children, a defiant representative of her husband and a self-defining agent of her own consciousness and courage as a mother, wife and Black woman, standing strong on that ever-present battleline for Black people. Indeed, as her son taught, “wherever a Black man (Black person) is, there is a battle line. Whether it’s in the North, South, East or West, you and I are living in a country that is a battle line for all of us”. Nana Louise was on that battle line that night and repeatedly, and it was a stance of great historical importance as both symbol and substance of our ongoing liberation struggle. It is his mother, Nana Louise, he tells us, who later told him of her defiant confrontation with the Klan and he remembers it and uses it to ground and frame his life story at the very beginning of sharing the awesome and instructive course of his complex life.

Haji Malcolm names his first chapter in his autobiography “Nightmare” to highlight the racist systemic violence of American society and the devastating impact on his mother and family and Black people as a whole. And in it, he reveals not only his love and respect for his mother, but also a message and model of resistance and resilience by his mother vital to any concept and practice of an irreversible choice and challenge to live, be ourselves and liberate ourselves against all odds, and regardless of the wily, wicked and shape-shifting ways of the oppressor.