This year and month marks the 57th anniversary of the assassination and martyrdom of El Hajj Malik El-Shabazz, Nana Min. Malcolm X, who offered and gave his life in the sacred and sustained struggle of his people for liberation and an uplifted life. In 1966, the year after his assassination and martyrdom, we of the organization Us designated February 21st as Siku ya Dhabihu, the Day of Sacrifice, and we have held communal events in commemorative appreciation of the awesome sacrifice Nana Malcolm made ever since. Indeed, as we’ve said so often, we honor him as both a model and mirror for our organization Us and our people.

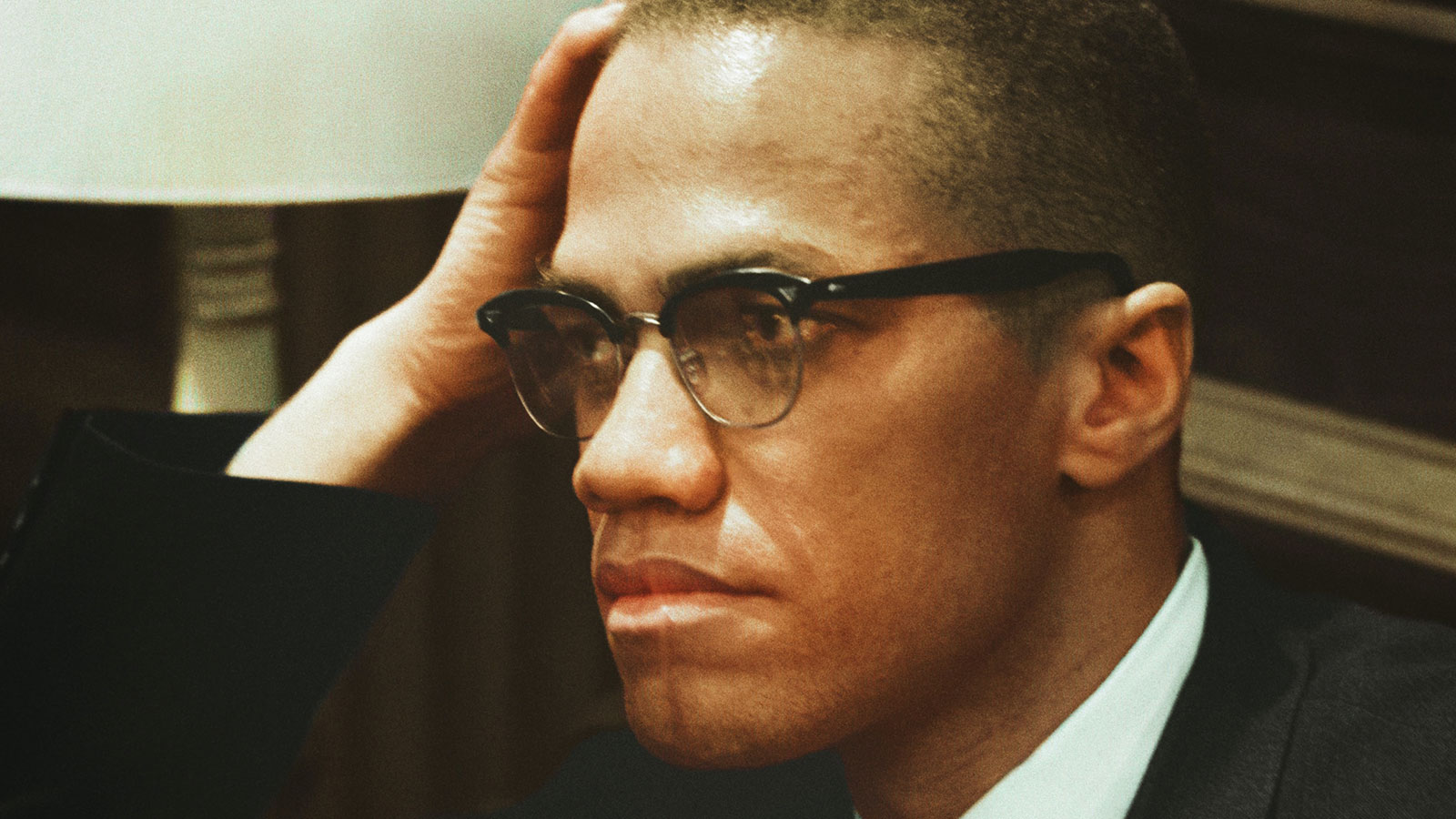

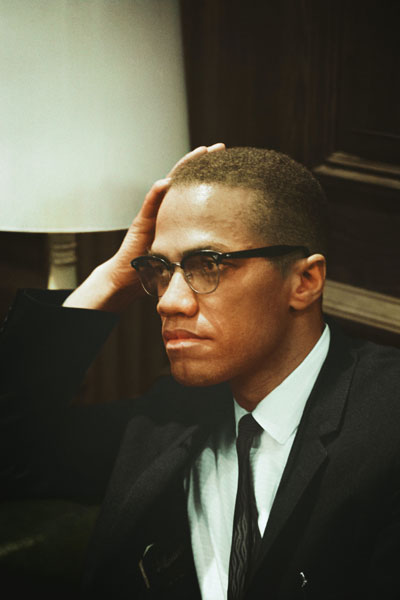

Malcolm X

This means he offers us an ethical model of dedication, discipline, sacrifice and achievement, the essential human material out of which heroes and heroines are made. And at the same time, he offers us through his life, work, teaching, struggle and even his death, a means to measure ourselves in our striving and struggling to live free, good and meaningful lives, be a faithful and fearless servant of our people, and leave a legacy worthy of the name and history African.

And so, once again, we are called, in our practice of the morality of remembrance, to come together in commemoration of this amazing miracle and unmovable mountain of a man, this towering tree in our sacred forest of revered freedom fighters. And we honor him and them, as Ossie Davis said in his eulogy for Nana Malcolm, for “in honoring him, we honor the best in ourselves.” Indeed, we honor the best and most beautiful, the sacred, the centering and sustaining within us and among us.

It is Malcolm, the man and martyr, the minister and moral teacher, the liberator and life-giver, the molder of men and women in righteous and upraised ways who taught us not only how to live, but also how to die. It is in this regard we talk more of his martyrdom than his assassination. For, as we always say, assassination is what his enemies and the enemies of our people and of human freedom did. His martyrdom, his conscious, committed and courageous self-sacrifice is what he dared to do and did.

Clearly, we must discuss the assassination, but not at the expense of the awesome sacrifice Haji Malcolm has made. Indeed, it is easy to make the oppressor and his conscious and unconscious instruments or allies the continued subject of our sentences and focus. This is so partly because so many of us have been cultivated and conditioned to focus on the negative, the pathological, perverse and weak rather than the positive, good, beautiful and strong. Thus, in the process we leave what Haji Malcolm has done, sacrificed and achieved mostly undiscussed and unappreciated. And we miss the meaning and morality of his martyrdom, his conscious and unbreakable commitment to make the ultimate and awesome sacrifice to live and die for the liberation and elevated life of his people.

He could have walked away from the battlefield before the war was won, stayed in Africa and/or Western Asia (The Middle East) and lived as already a revered freedom fighter and treated as a head of state. But he made a conscious and courageous decision to return to the U.S. under the real threat of certain death to continue his vital and invaluable service to his people and their liberation struggle to expand the realm of human freedom and justice in this country and the world. To borrow a phrase from our foremother and freedom fighter Nana Maria Stewart, Haji Malcolm “enters the field of action” and engages the liberation struggle as both a Black man and a Muslim. His faith is a central framework within which he understands and asserts himself as a noble witness to the world. He is both shahid, righteous witness, and mujahid, righteous solider, in the interest of freedom, justice and shared good in the world. And he gives his whole life to service and struggle, modelling and mirroring total commitment, as he said, “the one hundred percent dedication I have to whatever I believe in.”

He taught us a liberating and uplifting truth without fear, failure or falsification. As the honored ancestors taught, he committed himself “to bear witness to truth and set the scales of justice in their proper place among those who have no voice,” the silenced and subjugated, the downtrodden, degraded, disempowered and oppressed. He wanted his “life’s account, read objectively … (to) prove to be a testimony of some social value,” i.e., to enlighten, liberate, uplift and inspire us to constantly engage in transformative struggle. For at the heart of his work and struggle is the moral imperative to “wake up, clean up and stand up.”

Nana Malcolm is committed to self-giving as both service and sacrifice. He does not do things halfway, will not compromise or seek a comfortable position in oppression. Nor will he concede, explain away or refuse to assert his right and responsibility of righteous and relentless resistance. And he calls on us, all of his people, Black people, African people, to be conscious, morally grounded and actively engaged in the personal and collective struggle to be ourselves and free ourselves, and build the good world urgently needed and palpably possible.

Haji Malcolm urges us to seek and share the liberating truth of our history and humanity, as well as that of the world in which we live and die, are oppressed and in resistance, find allies and shape new horizons of history. He wants us to achieve moral grounding in the most expansive ways, conscious of ourselves as possessors of dignity and divine endowments of varied kinds. And he truly wants us to “recapture our heritage and our identity” as a beautiful, powerful and sacred people, if we are ever “to liberate ourselves from the bonds of white supremacy.” It is a call to cultural revolution, decolonizing the mind and heart, recovering and practicing the best of our culture and putting it in the service of our world encompassing and world-transformative liberation struggle. He teaches us that we “must recognize each other as brothers and sisters,” love each other, stop committing injury and injustice against ourselves and others, “wake up to our humanity,” defend and develop it and live it fully and righteously. He wants us to learn more about our beauty, goodness, sacredness, potential and power as a people and to use it all for the struggle to build the good community, society and world we deserve.

He reminds us of our history and the need to study it and to reject the oppressor’s version of both our history and his own. For he “has never given you and me true facts about history, neither about himself or about our people.” Nana Malcolm urges us to learn and live a history of struggle. He wants us to learn of heroes and heroines, models and mirrors who have lived and “died fighting for the benefit of Black people.” He speaks here of the leaders of the Haitian Revolution, Nana Toussaint L’Ouverture, Nana Jean-Jacques Dessalines, and leaders of the African American liberation struggle, Nana Nat Turner and Nana Fannie Lou Hamer.

The morality of sacrifice can and did lead to martyrdom for Nana Haji Malcolm. Sacrifice in the Kawaida tradition is self-giving in a deep and comprehensive way. It is giving of the heart and mind in conscious commitment, giving sufficient time and effort, giving material things as necessary and finally, giving the wholeness of oneself in life and even death, if necessary. Here Nana Malcolm’s teaching “Freedom by any means necessary” is key. For it speaks of “necessary” in two distinct and yet interrelated ways.

First, necessary refers to what the oppressor compels us to do to achieve our human right of freedom. Second, it refers to what we must be prepared and committed to give as the difficult, dangerous and demanding struggle for freedom requires. And Nana Malcolm declared and proved he was prepared and committed to give of himself, both his life and his death in the interest of African and human freedom, justice as both principle and practice, and the rightful hope for a new history of humankind. And at this critical juncture in our history and struggle, he leaves us with the urgent question: what are we prepared to sacrifice as the times and struggle demand it?

Photo by Unseen Histories on Unsplash