Black and Asian Solidarity Run at Union Square in New York City on March 21. A large crowd of people came together to show their support for the Asian community after the spa killings that occurred recently in Atlanta.

Nikki Ogunnaike had participated in Running to Protest’s rallies before, but never with her friend of more than 10 years, Lisa Lu. But on March 21, the two stood side by side at Union Square for the “Black & Asian Solidarity” protest—along with more than 1,000 other people. Ogunnaike, who is Nigerian American, had shared the details about Running to Protest with Lu, who is Vietnamese.

“I sent it to Lisa and I said, ‘Let’s get out there,’” Ogunnaike says. After a rally featuring speeches on fighting anti-Asian and anti-Black racism together, the thousand-plus protesters marched down Broadway. “Black lives matter. Asian lives matter,” they chanted in the streets of Lower Manhattan—many with outstretched arms, carrying signs that said “Stop Asian Hate.” Onlookers clapped on the sidewalks and drivers honked horns, with some lowering their windows to raise a fist in support. The crowd stretched on for blocks as more call-and-response chants sounded: “Show me what community looks like. This is what community looks like!”

Running to Protest’s “Black & Asian Solidarity” rally was organized weeks before the Atlanta-area spa shootings claimed the lives of eight people, including six Asian women, prompting a reckoning over the rise in the past year of anti-Asian violence and a long history of anti-Asian racism. But it quickly became one of several shows of Black and Asian solidarity following the Atlanta-area shootings, as people banded together over a common goal: dismantling white supremacy.

Shortly after the attacks, the official Black Lives Matter account issued a statement denouncing attacks against Asian Americans. “When we call for the eradication of white supremacy, we are saying that Asian Americans, and every other marginalized racial group, deserves to be freed from the violence, intimidation and fear,” read the statement. “None of us are free until we all are.” Ahead of the #StopAsianHate rally at Liberty Plaza in Atlanta on March 20, the NAACP shared multiple posts in support of the Asian community. Rev. James Woodall, State President of the Georgia NAACP, attended the rally and, a day later, had an Instagram Live discussion with journalist Lisa Ling on how white supremacy has impacted Black and Asian communities—and how the two groups can move forward together.

People march through a neighborhood to protest against anti-Asian violence on March 18 in MinneapolisStephen Maturen—Getty Images

The history of Black and Asian relations in the U.S. is fraught. Anti-Black racism has existed in the Asian community, and anti-Asian racism has existed in the Black community. The recent actions of solidarity come at a pivotal moment as calls for improving the security and safety of elder Asian Americans have sparked concerns about the next course of action. Community leaders have warned against more policing, given law enforcement’s pattern of disproportionately targeting Black and brown individuals. “We’re not safe until all people of color are safe. Safety doesn’t come in the form of heavier policing calls or of carceral state oppression of poor communities,” Dao-Yi Chow tells TIME. Chow, who is Chinese American, was one of the organizers of Running to Protest’s “Black & Asian Solidarity” rally. “That’s only continuing to align ourselves with white supremacy. And if we continue to do that, those are anti-Black acts that’s only going to continue to drive divisions in between our communities,” Chow says.

This dynamic of communities of color being pitted against one another is front of mind for many amid the rise in anti-Asian violence over the last year and has sparked a variety of initiatives aimed at building cross-racial unity. Eater reported that Bay Area-based cook Adrian Chang and herbalist Erin Wilkins, after becoming wary of an “Asian against Black” narrative that seemed to emerge as coverage of attacks that include suspects who were Black began to circulate nationwide, hosted “Dumplings for Unity” in February. The class was a fundraiser that would promote Black and Asian solidarity. During the same month, Oakland City Council president Nikki Fortunato Bas—a proponent of “multi-racial healing events” in light of the recent anti-Asian attacks—and the City of Oakland’s Cultural Affairs Commission hosted a “Stories of Solidarity” virtual town hall and concert aimed at highlighting AAPI and Black artists.

Black-Asian solidarity looks like taking down white supremacy

Black filmmaker and activist Coffey, who goes by his last name, founded Running to Protest in June 2020 following the murder of George Floyd. The movement has organized monthly runs in New York City dedicated to a range of causes, from raising awareness for missing and murdered Indigenous women to honoring Ahmaud Arbery in February, a year after he was killed in Georgia. For the most recent one, Coffey along with his protest partner Power Malu had worked with fashion designers Dao-Yi Chow, Prabal Gurung and Phillip Lim to organize a rally focused on addressing the surge in anti-Asian violence in the U.S. and building Black and Asian solidarity

“We put out the flier that morning. The events in Georgia happened that afternoon,” Coffey tells TIME, referring to the Atlanta-area shootings on March 16. “Seeing that, I can’t lie, I shed tears because to me, white supremacy gets away with way too much.”

Statements from police in Georgia following the attacks prompted widespread criticism. Authorities said the suspected shooter, who has since been charged with eight counts of murder, claimed that the attack “was not racially motivated” and that he had been trying to address a “sexual addiction”—seeming to elide how racism and misogyny can be intertwined. Rage over police conduct grew after a video circulated showing a member of the Cherokee County Sheriff’s Office explaining the alleged shooter’s actions as: “Yesterday was a really bad day for him and this is what he did.”

A mourner at a makeshift memorial for the victims of a shooting at Gold Spa in Acworth, Ga., March 19Jeenah Moon—The New York Times/Redux

“They labeled this thing as, ‘He was having a bad day,’” says Coffey. “That alone lets you know who the fight should be against.”

The rally included a moment of silence for the eight victims. Chow read aloud each of their names: Daoyou Feng. Hyun Jung Grant. Suncha Kim. Paul Andre Michels. Soon Chung Park. Xiaojie Tan. Delaina Ashley Yaun. Yong Ae Yue.

“Our call for solidarity is not necessarily asking Black or brown people to do anything, it’s a moral call to us, internally, as the Asian community to acknowledge our complicity in this web of white supremacy,” he tells TIME. Chow, who has known Coffey for about two decades, participated in multiple Running to Protest rallies before co-organizing the most recent one. “If we don’t address our own complicity in that web, then we can’t move forward as a community and then we can’t lean on allyship from Black or brown people to help support our struggle,” he adds.

Chow says the model minority myth—based on the stereotype that Asian Americans are hard working, law-abiding individuals and the false perception that such qualities have led to their success over other racial groups—has played a significant role in creating a wedge between Asian Americans and other BIPOC communities. “We were painted as an example, a ‘good minority.’ And then there were examples of ‘bad minorities,’ and that was perpetuated, which created even more divide,” Chow says. He says that among the earlier generation of Asian Americans who immigrated to the U.S., many assimilated to white adjacency in hopes that it would be the quickest path to safety and stability in the country.

The March 21 Instagram Live discussion between Woodall and Ling directly addressed the subject. “White supremacy always tries to convince those who are non-white that they must either assimilate, or somehow come to terms with the standard of whiteness,” Woodall says. He notes that in referring to “white,” he is discussing a mindset and not a color. “And if we don’t have access to that mindset—and quite honestly, I don’t want access to it—the question then becomes, how do we dissolve a society that is predicated upon that mindset in being in control.”

Looking at history alone isn’t always enough

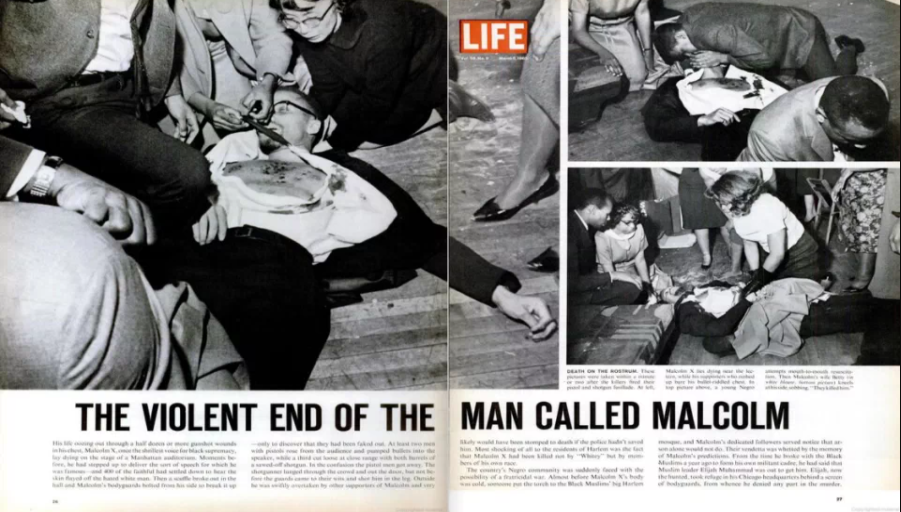

According to the sociologist and writer Tamara K. Nopper, who has studied Black-Asian solidarity and Black-Asian conflict for almost two decades, discussions over strengthening relations between the two communities often follow a similar pattern. “People will say, there’s a ‘hidden history,’ and then they’ll bring up some examples of that ‘hidden history,’” she tells TIME, referring to notable instances of solidarity. “They might talk about Asian Americans who supported the Black Panther Party. They might talk about Grace Lee Boggs and Yuri Kochiyama.” (Boggs, who was Chinese American and married Black activist James Boggs, dedicated much of her decades-long advocacy to fighting for the Black Power movement. Kochiyama was a Japanese American civil rights activist who befriended Malcolm X and joined his group, the Organization of Afro-American Unity.)

A photo by Malcolm X’s close associate Earl Grant shows Yuri Kochiyama (above left, in glasses) cradling the fatally wounded human rights activist’s head at the Audubon Ballroom in Harlem, Feb. 21, 1965.LIFE Magazine

While such examples are essential for better understanding the history of Black-Asian solidarity, Nopper suggests they do not paint the full picture. “People say, if we just knew more about this ‘hidden history,’ then we would have better relations,” she says. “The reality is, that is a very limited history. It is not the norm.” Historically, advocates who focused on building cross-racial unity were minorities within their own groups, Nopper says.

“We look at exceptions to think about possibilities, but we have to deal with what’s there,” she adds. Right now, Nopper says, that means looking at and openly addressing power relations between Black and Asian communities.

“Asian Americans, we just get treated better than Black people,” says Nopper, who is Korean American. She explains that a number of societal structures exist with the intention of trying to punish Black people—from the history of policing in the U.S. to the history of mass incarceration in the country. “Asian Americans—we experienced racial violence and we’re seeing upticks of COVID-related harassment,” Nopper says. “It’s not to say that we can’t experience racial violence. We do. It’s not to say that there aren’t specific ways that we get targeted. There are. But we’re not the basis of how people organize punishment through society in general.” Conversations about this reality should be happening alongside discussions about historical instances of Black-Asian unity.

“To me, the question is, how can we ever talk about serious coalition or serious solidarity if we’re not dealing with the elephant in the room, in terms of power relations,” she says. “How do we actually deal with white supremacy together if we’re not even dealing with power relations between ourselves.”

‘Not only when we’re under attack, but when everyone is under attack’

In the March 21 Instagram Live, Ling described how the COVID-19 pandemic has removed the metaphorical bandage on hidden wounds that have been festering—from the model minority myth to the “almost inattention” that some of those in her community have adopted toward social justice.

“For the most part, I think the Asian community has, culturally, wanted to keep its head down,” says Ling, who is Chinese American. But now, conversations that she describes as “a long time coming” are finally being had—including her discussion with Woodall.

Echoing her thought, Dao-Yi Chow draws attention to a shift occurring in the AAPI community. “We have new generations of young people and activists who never participated in that [model minority] narrative,” Chow says, “and who are down and will show up for Black and brown struggle, who will continue to fight for the greater social justice movement not only when we’re under attack but when everyone is under attack.”

Fashion designer Gurung, another organizer of Sunday’s protest, says physically showing up carries significance in solidarity efforts. He recalls that as the COVID-19 pandemic worsened in New York City last summer, he decided to stay in the city to participate in as many of the Black Lives Matter protests and marches as he could. “While I may not be the revolutionary, I knew that my body in those protests, one more body will add to the number to create the resistance, to create the revolution,” says Gurung, who is Nepali American.

The approach of showing up to fight for the liberties of all marginalized groups must happen consistently for change to take effect, Gurung says. “Even with my minority group I might be in a place of privilege. The most underprivileged are the Black trans women,” he adds. “I always feel like in these times we have to, in any possible way we can, show up for every marginalized group because that is the only way to dismantle white supremacy.”

Ogunnaike, who marched in Sunday’s Running to Protest alongside Lu, says she’s observed the growing solidarity from the Asian community to the Black community. “I wanted to come out today because I was active in the Black Lives Matter protests and I was really heartened to see Asians for Blacks and that community come out and support us,” Ogunnaike says.

“When we come together as a unit, we can be louder and we can finally get some justice,” Lu adds.

Ogunnaike acknowledges that people of color can fall into a trap of “wanting to be close to whiteness.” “But I often joke that white supremacy is the final boss, and that’s who we all should be going after,” she says.

Source: TIME