Covid-19 is disproportionately killing black people because the whole system is worse for us.

By Stacey Patton, The Washington Post —

Black America is ground zero for covid-19.

Alarming health department statistics from cities and counties in the Carolinas, Illinois, Louisiana, Michigan, New Jersey, New York and Wisconsin show that black people are getting sicker and dying at higher rates from the novel coronavirus than white people. Although the federal government hasn’t yet released data on the pandemic and race, the disparity looks likely to be a national trend, exacerbated by a combination of biased white doctors, black people’s well-documented distrust of the medical community and the failure to aggregate and properly report out data on the sick and dying.

Even President Trump has noticed. “Why is it that the African American community is so much, you know, numerous times more than everybody else?” he asked on Tuesday, adding: “It doesn’t make sense, and I don’t like it.”

But the answer to Trump’s question is obvious: Black people are at the mercy of everything that is flawed and dysfunctional about America’s health-care system, which has long been shaped by racism.

Decades of research show the ways that racism produces a rigged system that drives disparities in health outcomes across lifetimes and generations. Higher levels of discrimination and bias are associated with elevated risk of a broad range of diseases, from higher levels of stress hormones, to blood pressure, to obesity and early death. All of those underlying conditions put people at higher risk for bad outcomes from covid-19.

It doesn’t take “a very stable genius” to connect black people’s higher rates of unemployment, mass incarceration, chronic preexisting medical issues, poor housing, homelessness and less reliable access to quality health care to see why they’re more vulnerable to increased viral transmission, infection and death during a pandemic. Black people are also less likely to work in the kinds of jobs that will continue to pay you if you don’t physically show up in the office. As New York Times columnist Charles Blow pointed out this week, the ability to work from home, to practice social distancing and to wear a mask without fear of being arrested or shot while black are all forms of privilege.

This isn’t the first pandemic where the pathologies of American racism have exacerbated the pathologies of a virus.

The 1918 pandemic, the second-deadliest outbreak in human history, killed an estimated 675,000 Americans. When the flu first hit and overwhelmed the nation’s health care delivery systems, black illnesses went underreported in data collection efforts. News coverage of the flu’s impact on black communities was limited, because white society believed that the virus primarily affected white people. The assumption was that blacks were immune to the flu, partly due to the buffer of legalized segregation and pseudoscientific theories about black bodies.

Some physicians suggested that blacks were less susceptible to the type of influenza that struck in 1918 and that the lining of their noses made them more resistant to microorganisms that entered the upper respiratory tract.

“Few Negroes Die of ‘Flu,’ ” read a headline from a local newspaper in Boise. The same report highlighted that “undertakers at Stamford, Connecticut have been mystified at the scarcity of deaths among colored people as a result of the infection.” An afternoon edition of Maysville, Ky.’s Public Ledger noted, “against the flu the negro’s chance of life was almost twice as good as the white man’s. What underlies this phenomenon? Something beyond present determination.”

The Phoenix Tribune ran an editorial declaring God must be black (using a racist slur), because influenza seemed to spare black people, who were “better fortified against this particular germ.” A white female resident of the Eastern Shore of Maryland who heard the false claims about blacks being less affected by the flu said, “Well, that proves they are not human like the rest of us.”

The reality was that black communities were left to fend for themselves during the 1918 flu pandemic. They received substandard care in segregated hospitals that were already stretched thin and were turned away from white facilities when they were at death’s door. In cities like Baltimore, eyewitnesses described people dropping dead in the streets. Bodies were piled up in coffins on street corners, or decomposed for days in people’s homes, because morgues and cemeteries couldn’t handle the backlog of dead victims. Racist sanitation workers refused to dig graves for black people, who were often blamed for spreading the disease in big cities they had recently migrated to in large numbers.

With no financial cushion and no way to self-quarantine, black people carried the disease to their workplaces and on public transportation. Without access to medical care, they turned to anything they thought might help. The Chattanooga News interviewed a black washerwoman who shared an “old time” tea remedy made of catnip, rabbit leaf and mullein leaves that allegedly kept blacks from getting the flu. “You white folks don’t believe in teas, but that is all we colored folks take when we are sick,” she said.

Researchers have captured some public health data on the impact the flu had on black people living in a handful of cities, but back then, most health department records didn’t reflect the true number of sick or dead, especially along racial lines. Some communities didn’t report the disease; others lacked the ability to keep accurate records. Some places, overwhelmed, just gave up cataloguing the victims.

“The lack of accurate data collection during the public health crisis and the possibility that African American influenza cases may have been underreported because of inadequate access to medical care make it difficult to conclude definitively whether the incidence of influenza was lower in African Americans during the epidemic,” according to a 2010 study by medical historian Vanessa Northington Gamble.

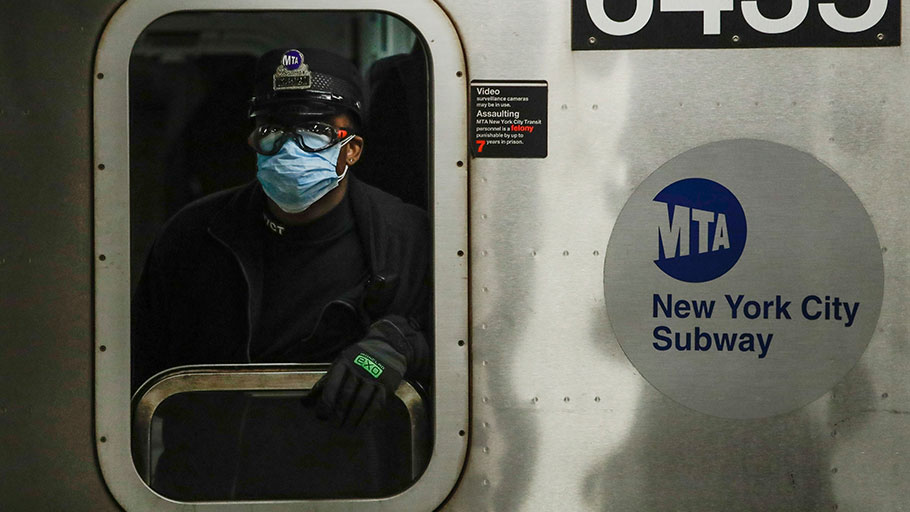

The same patterns are present today. Just as flu victims did 100 years ago, many workers — predominantly black and brown — are going to their “essential” jobs because without them, the rest of society wouldn’t function. Dozens of New York City mass-transit workers have died, and hundreds are sick.

The same types of false information, memes and jokes went around that black people were immune to this virus, this time on social media. One heavily retweeted Twitter user wrote: “So NONE of these Corona Virus cases have been black people?! LEMME FOUND OUT WE IMMUNE. It’s the least God can do after slavery.” As writer Brentin Mock has noted, these jokes and unsubstantiated claims about black people’s supernatural resilience to disease have led to devastating health outcomes for black people over the years, because such beliefs affect how they are treated or not.

The rumors were so rife that British actor Idris Elba addressed them when he tested positive. “Something that is scaring me, when I read the comments and some of the reactions, my people, black people, please, please understand that coronavirus is . . . you can get it,” Elba said. “There are so many stupid, ridiculous conspiracy theories about black people not being able to get it. . . . That is the quickest way to get more black people killed. And I’m talking about the whole world, wherever we are. . . . Just know you have to be just as vigilant as every other race.”

And while some city and state health departments are doing a better job of tracking this pandemic’s toll on black people than the nation did in 1918, the federal government is still blind. For weeks, a number of black journalists, academics and civil rights advocates have been frustrated by unanswered calls for data on race and covid-19.

“I suspect that some Americans believe that racial data will worsen racism. But without racial data, we can’t see whether there are disparities between the races in coronavirus testing, infection, and death rates,” Ibram X. Kendi, director of the Antiracist Research and Policy Center at American University, wrote in the Atlantic. “If we can’t see racial disparities, then we can’t see the racist policies behind any disparities and deaths. If we can’t see racist policies, we can’t eliminate racist policies, or replace them with anti-racist policies that protect equity and life. Without racial data, we can’t see racism, and racism becomes like asymptomatic carriers — spreading the virus, and no one knows it.”

On Tuesday, Trump said the White House coronavirus task force would be releasing data on race soon. That same day, I reached out to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to request nationwide data broken down by race. A spokesman there told me that the CDC has not yet collected statistics on infections and deaths by race because in the chaos of the pandemic, medical professionals on the front lines are moving so quickly that only the most basic level of reporting on victims has been collected.

A CDC statement said public health departments use a standardized case report form that captures a wide range of information, including ethnicity and race, symptoms, county and state of residence and preexisting medical conditions, but “unfortunately, case report forms are often missing important data, including race and ethnicity” because “health departments are under a tremendous amount of strain to collect and report case information.” The CDC is working to address data gaps with supplementary surveillance systems to better capture ethnicity and rate data, but it will probably take a few weeks.

As the death toll continues to rise, and as doctors appear to be less likely to refer African Americans for testing when they show up for care with signs of infection, will Trump’s administration really make data gathering on race a national priority?

And more troubling: Will fighting covid-19 become less of a priority if black folks become the face of the virus? Will the virus be weaponized against black communities and worsen the administration’s open hostility toward people of color? The pandemic won’t keep Trump’s administration from its attack on the Affordable Care Act, nor will it prompt states with large nonwhite populations to expand Medicaid coverage, which they’ve resisted all along. Will the loss of black lives to the virus free up real estate in gentrifying cities that have already removed large numbers of poor and working people of color?

Data is history, and it tells a difficult story about race in America. Collecting accurate statistics on who is dying along racial lines must be a national priority now. The long history that has made black people more vulnerable to the virus is the obvious, painful answer to the president’s disingenuous question of “why?”

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.

Stacey Patton is the author of “Spare The Kids: Why Whupping Children Won’t Save Black America” and the forthcoming “Strung Up: The Lynching of Black Children and Teenagers in America, 1880-1968.

Featured image: A New York MTA worker wears personal protective equipment at the Grand Army Plaza subway station in Brooklyn. The coronavirus is disproportionately sickening and killing black Americans. (Frank Franklin II/AP)