By Stacy M. Brown, NNPA Newswire —

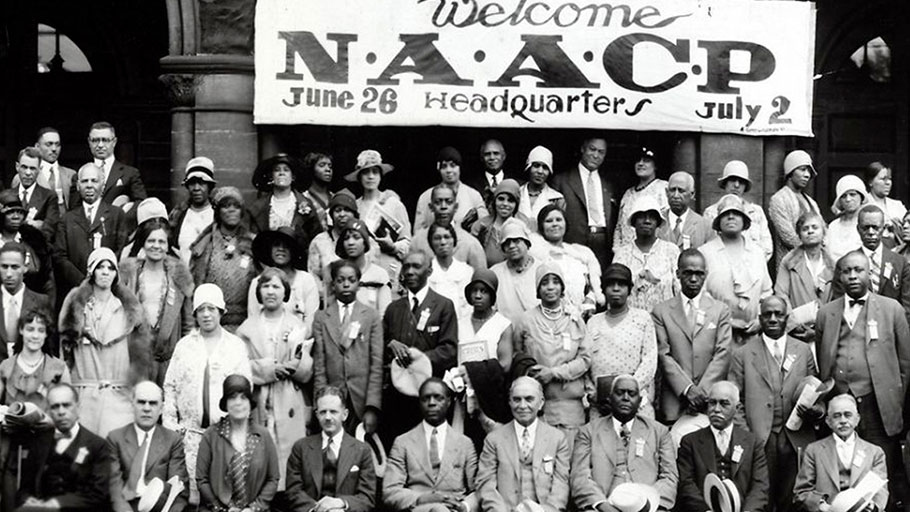

The NAACP plans to highlight 110 years of civil rights history, and the current fight for voting rights, criminal justice reform, economic opportunity and education quality during its 110th national convention now happening in Detroit.

The five-day event which began on Saturday, July 20, will also include a session on the 2020 Census, a presidential roundtable, CEO Roundtable, and LGBTQ and legislative workshops.

“We are excited to announce the 110th annual convention in Detroit, my hometown,” said NAACP President and CEO Derrick Johnson.

“For me, it is a homecoming and I will also be excited to announce our theme for this year which is, ‘When we Fight, We Win,’” Johnson said.

Winning is what the NAACP was built on – winning battles for racism, freedom, justice and equality.

The NAACP was formed in 1908 after a deadly race riot that featured anti-black violence and lynching erupted in Springfield, Illinois.

According to the storied organization’s website, a group of white liberals that included descendants of famous abolitionists Mary White Ovington and Oswald Garrison Villard; William English Walling, and Dr. Henry Moscowitz, all issued a call for a meeting to discuss racial justice.

About 60 people, seven of whom were African American, including W. E. B. Du Bois, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, and Mary Church Terrell, answered the call, which was released on the centennial of the birth of President Abraham Lincoln.

“Echoing the focus of Du Bois’ Niagara Movement for civil rights, which began in 1905, the NAACP aimed to secure for all people the rights guaranteed in the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the United States Constitution, which promised an end to slavery, the equal protection of the law, and universal adult male suffrage, respectively.”

Accordingly, the NAACP’s mission remains to ensure the political, educational, social and economic equality of minority group citizens of United States and eliminate race prejudice.

“The NAACP seeks to remove all barriers of racial discrimination through democratic processes,” Johnson said.

The NAACP established its national office in New York City in 1910 and named a board of directors as well as a president, Moorfield Storey, a white constitutional lawyer and former president of the American Bar Association.

Other early members included Joel and Arthur Spingarn, Josephine Ruffin, Mary Talbert, Inez Milholland, Jane Addams, Florence Kelley, Sophonisba Breckinridge, John Haynes Holmes, Mary McLeod Bethune, George Henry White, Charles Edward Russell, John Dewey, William Dean Howells, Lillian Wald, Charles Darrow, Lincoln Steffens, Ray Stannard Baker, Fanny Garrison Villard, and Walter Sachs. Despite a foundational commitment to multiracial membership, Du Bois was the only African American among the organization’s original executives.

Du Bois was made director of publications and research, and in 1910 established the official journal of the NAACP, The Crisis.

By 1913, with a strong emphasis on local organizing, the NAACP had established branch offices in such cities as Boston, Baltimore, Kansas City, St. Louis, Washington, D.C., and Detroit.

NAACP membership grew rapidly, from around 9,000 in 1917 to around 90,000 in 1919, with more than 300 local branches.

Joel Spingarn, a professor of literature and one of the NAACP founders formulated much of the strategy that fostered much of the organization’s growth.

He was elected board chairman of the NAACP in 1915 and served as president from 1929-1939.

The NAACP would eventually fight battles against the Ku Klux Klan and other hate organizations.

The organization also became renowned in American Justice with Thurgood Marshall helping to prevail in the 1954’s Brown v. Board of Education, the decision that overturned Plessy.

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, which was disproportionately disastrous for African Americans, the NAACP began to focus on economic justice.

Because of the advocacy of the NAACP, President Franklin D. Roosevelt agreed to open thousands of jobs to black workers when labor leader A. Philip Randolph, in collaboration with the NAACP, threatened a national March on Washington movement in 1941.

President Roosevelt also set up a Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC) to ensure compliance.

The NAACP’s Washington, D.C., bureau, led by lobbyist Clarence M. Mitchell Jr., helped advance not only integration of the armed forces in 1948 but also passage of the Civil Rights Acts of 1957, 1964, and 1968 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

NAACP Mississippi field secretary Medgar Evers and his wife Myrlie would become high-profile targets for pro-segregationist violence and terrorism.

In 1962, their home was fire bombed, and later Medgar was assassinated by a sniper in front of their residence. Violence also met black children attempting to enter previously segregated schools in Little Rock, Arkansas, and other southern cities.

The Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s echoed the NAACP’s goals, but leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr., of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, felt that direct action was needed to obtain them.

Although the NAACP was criticized for working too rigidly within the system, prioritizing legislative and judicial solutions, the Association did provide legal representation and aid to members of other protest groups over a sustained period of time.

The NAACP even posted bail for hundreds of Freedom Riders in the ‘60s who had traveled to Mississippi to register black voters and challenge Jim Crow policies.

Led by Roy Wilkins, who succeeded Walter White as secretary in 1955, the NAACP collaborated with A. Philip Randolph, Bayard Rustin and other national organizations to plan the historic 1963 March on Washington.

The following year, the Association accomplished what seemed an insurmountable task: The Civil Rights Act of 1964.

“Much has changed since the creation of the NAACP 110 years ago, and as we highlight these achievements during this year’s convention, we cannot forget that we’re still tirelessly fighting against the hatred and bigotry that face communities of color in this country,” Johnson said.

“With new threats emerging daily and attacks on our democracy, the NAACP must be more steadfast and immovable than ever before to help create a social political atmosphere that works for all,” he said.

The NAACP provided all historical information for this report.