The slave trade not only physically separated African Americans and Africans, but it created a psychological separation as well. At the root of this continued division between the two groups are misconceptions rooted in the narratives that each group has been given about themselves, as well as each other. As African people we continue to view ourselves and each other through the lens of the colonizer. For this reason African Americans tend to view Africans in the same manner as Europeans do, and Africans tend to view African Americans the same way. In this article I will look at the roots of where these misconceptions came from.

African Americans were told that Africa was the “Dark Continent.” Africa was presented as the land of primitive savage cannibals who ran around the jungles of Africa naked. This narrative served multiple purposes. It lowered the self-esteem of the enslaved population by making them believe they were a people with no history or culture. In fact, many enslaved Africans came to see slavery as a benefit because it took them away from the savagery of Africa and introduced them to civilization and Christianity. This was the view that Phillis Wheatley expressed in her poem about being taken away from her “pagan land” and being introduced to Christianity in America. These depictions of Africa were also used by European slave traders to justify the slave trade by claiming that they were saving the souls of the “heathen” Africans by taking them away from Africa to be enslaved.

This propaganda was so effective that some African Americans bought into the notion of Africa being the Dark Continent. I gave the example of Phillis Wheatley, but she was far from the only one that held the view that Africa was a pagan or heathen land. Many of those who settled in Liberia held the view that Africa needed to be civilized. These settlers (known as Americo-Liberians) displayed some the attitudes of cultural superiority that European colonizers displaying in their dealings with Africans. To this day there are African Americans like Jesse Lee Peterson and Kimberly Daniels who have thanked God for slavery for taking them away from Africa. Then there are those like Herman Cain who do not even like being called African American.

W.E.B. Du Bois very aptly described how the negative view of Africa had influenced by African Americans to disassociate themselves from Africa when he wrote:

Among Negroes of my generation there was not only little direct acquaintance or consciously inherited knowledge of Africa, but much distaste and recoil because of what the white world taught them about the Dark Continent. There arose resentment that a group like ours, born and bred in the United States for centuries, should be regarded as Africans at all. They were, as most of them began gradually to assert, Americans.

This negative view of Africa has driven many African Americans to distance themselves from Africans or “African booty scratchers”, which is a derogatory term which was used by African Americans for African immigrants. For African Americans, anything African was negative. The short documentary below shows a 17 year old girl complaining that her mother told her to stop wearing her hair natural because it looked African. So what we must understand is that much of the negativity that African Americans have expressed towards Africans over the years comes from a place of self-hatred and a general lack of understanding about Africa.

I have also noticed recently that some African Americans have been expressing the view that Africans are very tribal, which is yet another colonial caricature that was created to demean Africans. Some people within the American Descendants of Slavery (ADOS) movement have being trying to present the ADOS identify as being a tribe, so that African Americans can have a tribal identity of their own. The problem is that these individuals actually do not understand the complexity of ethnic identity in Africa or the fact that tribalism in Africa is largely a product of European colonialism. I know from my experiences discussing African history with people that some African Americans are surprised to discover that the ethnic differences between the Hutu and Tutsi were essentially created by the European colonizers. So a lot of the perceptions that African Americans have of Africans seem to be rooted in the colonial narratives about Africans.

On the other side of this divide are Africans who have developed certain misconceptions of their own regarding African Americans. African American history is not taught in Africa — I have had experiences with this with people from Africa who really did not understand how brutal slavery and segregation was for African Americans. I have also found that much of what Africans do know about African Americans is based on what they see through the American media, which has a very global impact. This means that Africans are often exposed to some of the very negative images that the American media portrays of African Americans as being gangsters, drug dealers, etc.

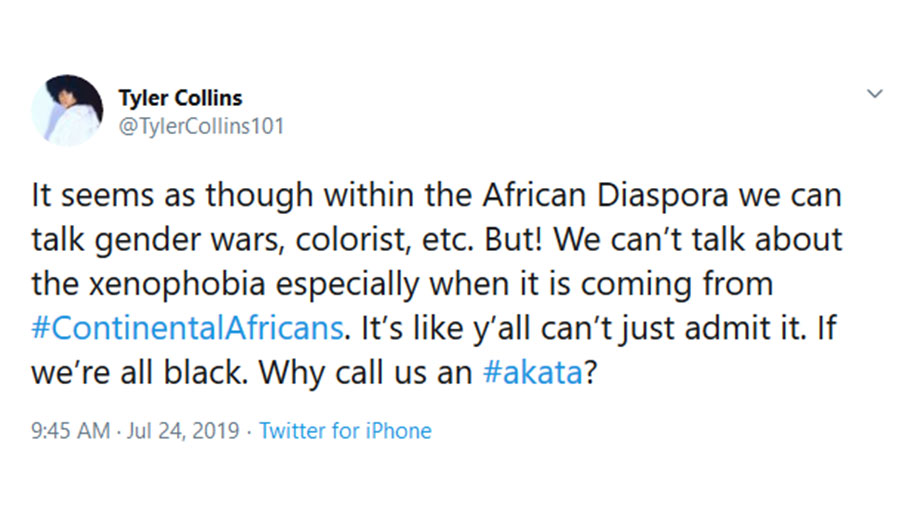

One of the more controversial aspects of the relationship between African Americans and Nigerians especially is the word “akata.” Akata is a Yoruba word which roughly translates to “wild cat” or a cat without a home. I have not been able to determine precisely how or why this term became associated with African Americans. I have come across several theories. One entry in Urban Dictionary explains:

Contrary to popular opinion among non-Yorubas and some Nigerians or Africans who does not understand this word, akata does not mean cotton picker or slave and it is not derogatory.

It means a cat that doesn’t live at home like a wild non domesticated cat, this is used to reference mostly African Americans as they are considered Africans by all Africans but the fact that they don’t live in Africa make them akata while those of us who live at home can be considered as Ologbo (cat).

I also came across an article which asserted that the word “ become widely associated with Black American people in the mind’s eye of young Nigerian immigrant students during the Black Panther Party’s high visibility on college campuses in the 1960s-1970s, when our radical youth claimed their identities as displaced African people on the world’s stage.” Regardless of how or why the term akata became associated with African Americans, the word has become something that is used as a way to demean African Americans.

The work akata also seems to be part of the perception that some Africans seem to have about African Americans being a people without a real culture. Mike Yard dealt with this topic in a very comedic manner:

Mike Yard is a comedian, but the topic that he is speaking about is a real issue. This sense that African Americans are not truly African is something that Zipporah Gene expressed in an article titled “Black America, Please Stop Appropriating African Clothing and Tribal Marks.” Zipporah writes:

I’m not trying to start a war, but I would just like you all to realize the hypocrisy of seeing someone wearing a Fulani septum ring, rocking a djellaba, painted with Yoruba-like tribal marks, all the while claiming that this is meant to be respectful. It’s a hodgepodge, a juxtaposition, a right mess of regional, ethnic and cultural customs and it screams ignorance and cultural insensitivity.

I actually do not see an issue with African Americans mixing together different ethnic cultural customs because African Americans are themselves a blend of different ethnic groups. Akan, Yoruba, Igbo, Mandé, Fulani, Kongo, Temne, Ewe, Edo, Efik, Fon, Mossi, and Ga are just some of the many ethnic groups that African Americans descend from. Zipporah is actually the one expressing cultural insensitivity by failing to recognize that African Americans descend from several different African cultures, so there is no contradiction in an African American mixing Fulani and Yoruba culture.

We also cannot overlook the fact that the Black Power movement among African Americans in the 1960s and 1970s helped to influence a cultural revival among Africans. The Nigerian musician Fela Kuti explained: “It’s crazy; in the States people think the black power movement drew inspiration from Africa. All these Americans come over here looking for awareness, they don’t realize they’re the ones who’ve got it over there. We were even ashamed to go around in national dress until we saw pictures of blacks wearing dashikis on 125th street.” Africans on the continent experienced colonialism and to this day there still are many Africans on the continent who do not have a proper appreciation for their own culture.

Even in Africa there has always been a great diffusion of cultures throughout the continent. This is a point that Trinidadian historian Hollis Liverpool made when he wrote:

Today Nigerian folk tales may be heard in Senegal, and the trickster hare of Zaire performs the same mischief as the spider trickster in Ghana and Togo. Similarly, West African musical instruments are equally known in the East and the South. The interplay of cultures and traditions of African kingdoms, states and empires before they were intruded upon by explorers, tell us something of the political and economic dynamics of the African continent then: an interplay of peoples and organizations.

So among African people there was never a sense that cultural customs belong to any particular group. The trickster spider and the trickster hare that Dr. Liverpool mentioned would seem like very familiar characters for those of us in the diaspora who grew up with Br’er Anansi and Br’er Rabbit stories, not realizing that these stories have their origins in Africa.

The culture of African Americans and others in the diaspora has also influenced Africa’s culture. Princess Sikhanyiso Dlamini of Eswatini (Swaziland)was inspired to become a rapper because of because of the connection she noticed between traditional Swazi music and the rap music who developed in the United States. So among African people there has always been an exchange of cultures across the continent, as well as between the diaspora and the continent.

I think much of the division that exists today between African Americans and Africans (as well as Caribbean Africans) is that we have misconceptions of each other which are rooted in ignorance of each other’s historical and cultural experiences. For example, how many Africans are aware of the role that the African diaspora played in the struggle against colonialism in Africa? And how many African Americans are aware of the influence that African’s independence had on the civil rights movement. The histories and struggles of Africans on both sides of the Atlantic have always been connected to each other. Once we became aware of this we can work on bridging this divide.

Dwayne Wong (Omowale) is the author of several books on the history and experiences of African people, both on the continent and in the diaspora. His books are available through Amazon. You can also follow Dwayne on Facebook and Twitter.

Featured image: African/African American Unity (1993-95 J.C.H). Retrieved from https://medium.com/@dwomowale/understanding-the-division-between-african-americans-and-africans-7dfb48b4808b