All of them returned to the South’s frontline struggle for racial justice.

In 2020, January remembrances of Martin Luther King Jr. are occurring against the backdrop of two high-profile films emphasizing sacrificial servant leadership.

First, the film Harriet provided a renewed focus on celebrated abolitionist Harriet Tubman. This biopic chronicles her mid-19th century enslavement in Maryland, her daring escape to a hard-won freedom in Philadelphia, and her selfless decision to return to the South multiple times to lead others on the treacherous journey from slavery to northern freedom.

Harriet effectively captures the alarm among Tubman’s abolitionist hosts in Philadelphia at the idea of her returning South on these perilous missions. But Tubman’s actions were guided by deeply held convictions, as conveyed through her own published words, and in revised form within the film:

I had crossed de line of which I had so long been dreaming. I was free; but . . . my home after all was down in de old cabin quarter, wid de ole folks, and my brudders and sisters. [And] to dis solemn resolution I came; I was free, and dey should be free also.

For Tubman, freedom could never be understood as singular. She could not live fully into her own freedom, conscious of the continuously shackled existence of those she left behind.

This month also saw the release of the film Just Mercy, which tells the story of attorney Bryan Stevenson’s relentless pursuits of due process for Alabama death row inmates. Born and raised in Delaware, Stevenson’s exposure as a Harvard Law School student to legally flawed convictions of death row inmates, particularly in the South, became for him a matter warranting urgent attention.

Upon graduating, Stevenson decided, counter to all expectations about his career trajectory and despite personal dangers he might face, to return to the South to provide legal counsel to persons condemned to death. He went on to found Equal Justice Initiative, a Montgomery-based organization that has “won reversals, relief, or release” for hundreds of “wrongly convicted or unfairly sentenced” prisoners, including 135 death row prisoners.

Stevenson would have us know, as stated in the film: “We can’t change the world with only ideas in our minds. We need conviction in our hearts.”

These accounts parallel the familiar sacrifices of Martin Luther King, Jr., who envisioned a path from his Boston University graduate studies to a career in the academy but returned to the South’s mid-20th century frontline struggle for racial justice, which led ultimately to his assassination.

As King would later say: “No one is free until we are all free.”

Today, although an ever-growing portion of African Americans press toward new social heights, a troublingly large portion of African Americans seem inescapably marginalized.

A persistent black marginalization has been masked by substantial social gains since the civil rights movement among a segment of African Americans that has achieved upward mobility, especially as a result of access to higher education.

The African American middle-class (defined in terms of persons working in non-manual, white collar jobs), was estimated by sociologist Bart Landry at 28 percent in 1970, 39 percent in 1980, 44 percent in 1990, and 51 percent in 2002.

Moreover, the percentage of African Americans with college degrees increased from 6 percent in 1970 to 19 percent (or 3.9 million persons) in 2011. Of that number, 1.6 million possessed advanced degrees (master’s, doctoral, or professional degrees) as compared with 677,000 blacks with advanced degrees in 1995.

Nevertheless, these social gains have occurred alongside a deepening and thickening of black poverty. Although the number of African Americans living below the poverty line in fact declined from 42 percent in 1966 to below 30 percent by 2008, several additional social indicators clarify the severity of black poverty and the reality of social isolation and marginalization evident among a large segment of blacks.

Particularly noteworthy has been the high unemployment rate among African-American youths age 16-19, which ranged between 23 percent and 48 percent from 1991-2010, and only recently declined to a low of 15 percent. Also of concern is a high school dropout rate among African Americans age 16-24, which has fluctuated between 10 and 15 percent throughout the 2000s (as compared to a rate of five percent or less among whites). Although by no means the only factor, high dropout rates contribute to the fact that roughly 80 percent of African Americans are without a college degree.

These economic and educational bifurcations among African Americans — and increasingly among Americans in general — raise nettlesome questions about possibilities for social mobility within the U.S.

Noted poverty analyst Douglas S. Massey makes a clear case against social mobility as a generalizable prospect within the American context. Massey details, instead, systematic impediments to social mobility deriving from America’s “allocation of people to social categories” and its “institutionalization of practices that allocate resources unequally across these categories.” The result, as Massey shows, is an “enduring” stratification tending to lock persons in place “across time and between generations,” and largely precluding upward mobility across class lines.

Urban slums are a contemporary spatial embodiment of this, as a growing percentage of blacks reside in neighborhoods where 40 percent or more of the residents are below the poverty line. The percentage of African Americans living in concentrated poverty rose from 8 percent in 1970, to 16 percent in 1990, to 23 percent in 2011. Moreover, recent research has shown that “concentrated poverty is tightly correlated with gaps in educational achievement.” As data confirm, there are virtually no poor school districts in the U.S. “where kids are performing at least at the national average.”

What also epitomizes concentrated black poverty and isolation is America’s outsized prisoner population. The amount of people incarcerated in U.S. prisons and jails rose from roughly 200,000 in 1970 to 2.2 million in 2017, and another 4.5 million persons were under supervised parole or probation by 2018. The vast majority of these persons are poor and are disproportionally persons of color.

In confronting American educational inequities, carceral culture, or other factors that have frustrated collective advancement, many African Americans in more fortuitous circumstances have mobilized intellectual, institutional, and financial resources in efforts to bridge persons out of socially marginalized confines.

As Tubman’s, King’s, and Stevenson’s examples make clear, expanding social promise for those at the social margins may require us circling back more directly to these confined spaces in order to personally point the way to a better future.

Such examples of sacrificial service provide a leadership standard deserving much greater emulation.

R. Drew Smith, Ph.D. is a professor at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary and co-convener of the Transatlantic Roundtable on Religion and Race. He can be followed on Twitter @RDrewSmith1

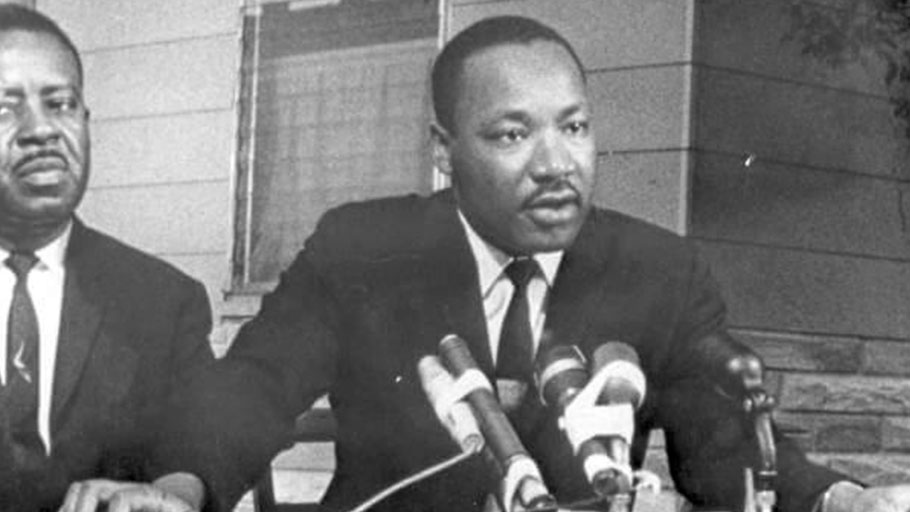

Featured image: Martin Luther King Jr. and Ralph Abernathy in St. Augustine, Florida. June 1964.