The 1831 narrative by Omar ibn Said is the only known surviving slave account of its kind.

By Michael E. Ruane, The Washington Post —

As a slave, he was called “Morro” or “Uncle Moreau.”

A dignified man in his 60s, he was small in stature, unfit for hard work and had been enslaved for almost a quarter-century. He spoke limited English.

But his real name was Omar ibn Said. He had been a Muslim scholar in West Africa, where he was abducted in 1807. And in 1831, when few enslaved people in the United States could read or write, he wrote what is thought to be the only surviving slave narrative of its kind, in Arabic.

The Library of Congress announced last week that it had acquired the famous memoir, along with a trove of related documents, from a noted African American collector and posted them online.

The collector, Derrick Beard, died in July in Las Vegas at age 59, just as the library was preparing the collection for display. Beard, who was Muslim, had owned and exhibited the document across the country for 20 years.

“He was determined that we should get it,” said Mary-Jane Deeb, chief of the library’s African and Middle Eastern Division. “He believed that it should be available to all Americans … not just to a private collector. It was very sad. … He was so sick. … He would say, ‘Are you buying it? Are you going to buy it?’ ”

“A couple of months after we bought it, he died,” she said. “I can only say that he must have died happy, because the manuscript came to the library, where he wanted it to be.”

The narrative of Omar ibn Said is brief, fragmented and subversive: It opens with Surah, or chapter, 67 from the Koran, which states that God has dominion over all things.

“Of all the chapters in the Koran, he picked that one,” Deeb said. “In Islam, everything belongs to God. No one really is an owner. … So the choice of that verse is extremely important. It’s a fundamental criticism of the right to own another human being.”

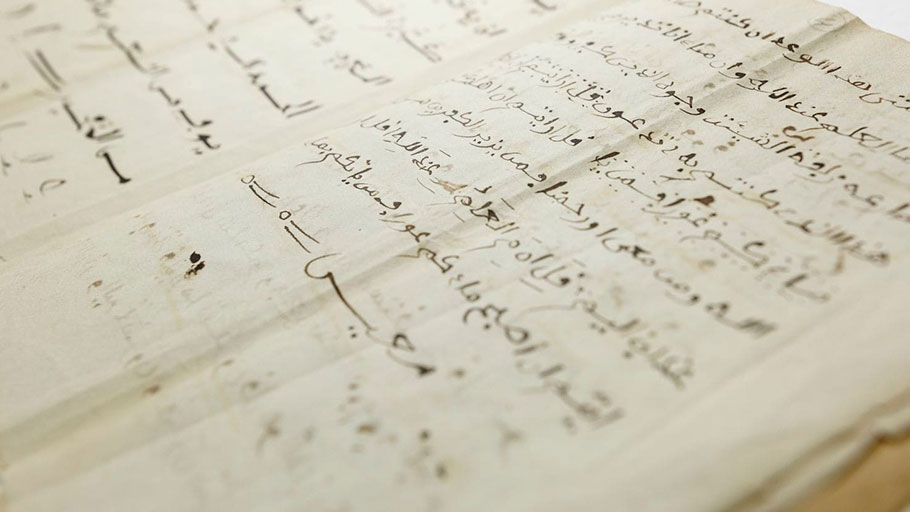

Written in Arabic script on paper in iron gall ink, and with a brown paper cover, the document warns of God’s fiery punishments yet acknowledges the author’s “good” treatment at the hands of his owners.

“It is very important … for many reasons,” Deeb said. “First … it’s an autobiography written by a slave while he was still a slave. He’s not a freed man. He dies a slave.” (Ibn Said died in 1864 in his 90s, in the midst of the Civil War, before slavery’s demise.)

Also, as a result of years of Islamic studies in Africa, he wrote in Arabic, which few people in the United States, almost certainly including his owners, could read. “He could be more candid,” Deeb said. Any literacy among American slaves was considered dangerous and was generally forbidden.

In addition, “as far as we know, this is the only extant manuscript of a slave in Arabic, still in existence … written in the United States by a slave who’s still a slave,” she said.

The library bought the collection in the summer of 2017 from Sotheby’s in London, Deeb said. She said the sale did not involve an auction. She declined to discuss the price and said she did not know why the collection was in London.

About 10 to 15 percent of American slaves were Muslim

“My name is Omar ibn Said,” the author wrote in his narrative — the preservation of his name a triumph in itself.

“My birthplace is Fut Tur (in modern-day Senegal). … I sought knowledge [and] continued seeking knowledge for 25 years. … [Then there] came to our country a big army. It killed many people. It took me and walked me to the big Sea, and sold me into the hand of a Christian man who bought me and walked me to the big Ship in the big Sea.”

This was probably about 1807. Ibn Said was then 37, and after studying for 25 years, “he must have learned philosophy, theology, astronomy,” Deeb said. “This is what you expect for those who go beyond the reading, writing, and learning the Koran by heart.”

The language of education was Arabic, she said, but ibn Said also spoke one of the local languages of his area.

After his abduction, he was likely taken to the port of Saint-Louis, in what now is Senegal, then to Charleston, S.C., according to historian Sylviane A. Diouf. He was probably aboard one of four American slave ships sailing from Saint-Louis that year that delivered 385 enslaved Africans to Charleston, she wrote.

“We sailed in the big Sea for a month and a half until we came to a place called Charleston,” ibn Said recounted. “And in a Christian language, they sold me. A weak, small, evil man called Johnson, an infidel who did not fear Allah at all, bought me.”

But ibn Said soon fled and made his way to North Carolina, where he was captured around Fayetteville. He was jailed, then handed over to plantation owner and future congressman James Owen, the brother of John Owen, a future governor of North Carolina.

One old account states that authorities took notice when ibn Said scrawled “piteous petitions” in Arabic on the walls of the jail.

Ibn Said then spent the rest of his life with the Owen family in Bladen County, N.C., at their plantations on the Cape Fear River.

He soon became a celebrity.

People were struck by his dignity and bearing, Deeb said. He was the subject of newspaper articles and visits by “scholars.” Some were eager to claim that he was an Arab, whose people were “not Negroes,” according to historian Ala Alryyes, an expert on ibn Said’s life.

“Let not the humanizing influence of the Koran upon … pagan, homicidal Africa be depreciated,” one Southern diplomat wrote.

Ibn Said embraced Christianity to a degree, and reportedly read an Arabic version of the Bible his owner acquired for him.

He praised James Owen, his owner, and Owen’s bother, John, as “good men, for whatever they eat, I eat, and whatever they wear they give me to wear.”

It’s not entirely clear why ibn Said decided to write his narrative, or for whom it was intended. Perhaps it was for other Muslim slaves in the United States, Deeb said. Estimates are that 10 or 15 percent of enslaved people in the United States were Muslim.

Perhaps he sought a different audience.

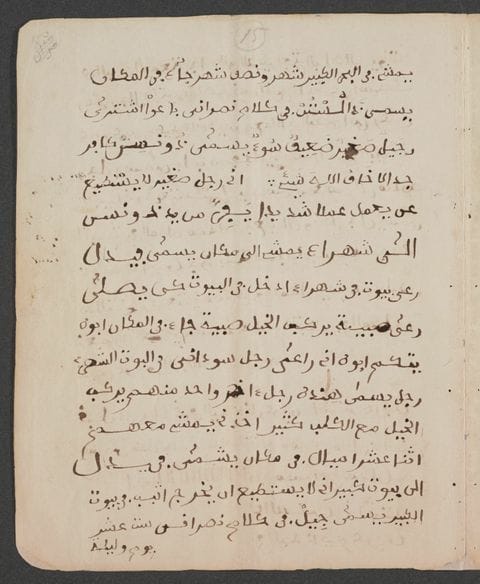

A page of Omar ibn Said’s autobiography, written in Arabic in 1831, in which he describes his abduction and transfer to South Carolina. (LIbrary of Congress)

“It’s part of the history of this country”

“From Omar to Sheikh Hunter,” he wrote at one point in the manuscript. “You asked me to write my life. I cannot write my life for I have forgotten much of my talk (language) as well as the talk of the Arabs.”

It’s not exactly known who Sheikh Hunter was. It might have been the Rev. Eli Hunter, of the American Colonization Society, a group that urged free blacks to move to Africa, according to Alryyes.

In 1836, the manuscript was sent to a Muslim former slave named Lahman Kebby, or “Old Paul,” in New York, who came from ibn Said’s home region in West Africa.

Kebby then gave it to Theodore Dwight, a founding member of the American Ethnological Society, who built the collection of Arabic manuscripts, translations of Arab manuscripts, and letters and news clippings on the subject that the library has acquired.

The narrative and the collection passed through various hands and dropped out of sight for most of the 20th century, Deeb said.

According to journalist Jonathan Curiel, the collection resurfaced in Alexandria in a trunk found by descendants of prominent numismatist Howland Wood, an authority on Islamic coins, who had owned it.

On March 28, 1996, Diouf, who was writing a book about Muslim slaves in the United States, walked into New York’s Swann Galleries to attend its first specialized auction of printed and manuscript African Americana, including the ibn Said collection.

She was not there to bid. “I just wanted to see the manuscript,” she said. There, she met Beard.

“I did not know him,” she said. “He was this very sociable, always smiling, very engaging kind of a person.”

“He told me that he was Muslim and he was interested in buying this collection,” she said. “It was interesting because he was the only bidder. No one else was interested, … It was kind of shocking. Because I thought that people would have been fascinated.”

Swann said the collection sold for $21,850.

“I think that as an African American, as a Muslim, and as a collector of African American art and material culture, he felt a deep personal responsibility toward that particular piece,” she said. “It was not like he had bought it to make money. … He was very keen on sharing the documents and the stories.”

“With Derrick, we always knew where it was, and that he would take care of it and share it,” she said.

Diouf said Beard had cancer. She said she did not know whether he had started selling items from his collection because of his illness.

But she said he wanted the ibn Said documents to stay in the United States. “It’s part of the history of this country,” she said. “It’s part of the American story.”