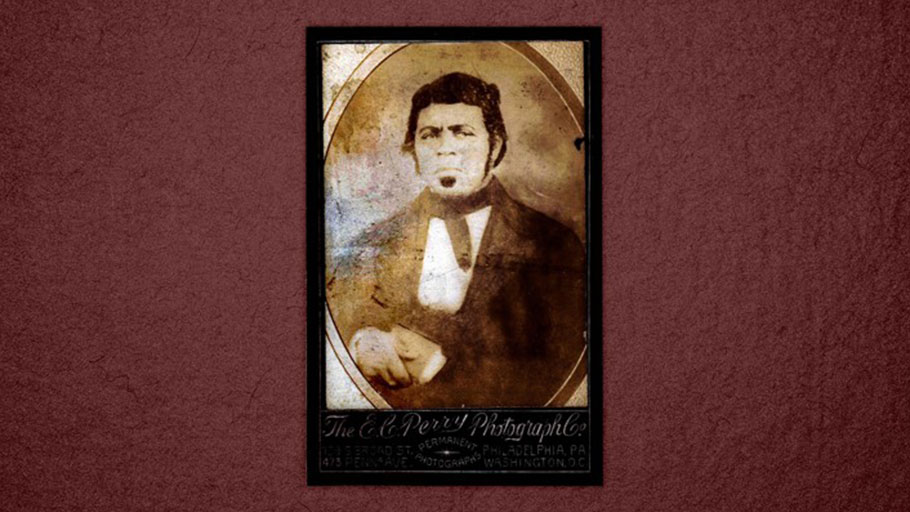

Paul Jennings, an enslaved man who served President James Madison and his family. Sylvia Jennings Alexander Estate, The Atlantic

Some presidential estates and other historical sites have struggled to reconcile founding-era exceptionalism with the true story of America’s original sin.

By Talitha LeFlouria, The Atlantic —

The story of Sally Hemings—the enslaved woman who bore six of Thomas Jefferson’s children—is told from the basement of Jefferson’s mansion at his Monticello plantation in Charlottesville, Virginia. The third American president’s legacy barely touches the brick floors and plastered walls of Hemings’s windowless room, their two lives more unconnected at Monticello today than they were in 1791.

At George Washington’s Mount Vernon estate, slavery is similarly separated from the nation’s founding father. A temporary exhibition, “Lives Bound Together: Slavery at George Washington’s Mount Vernon,” explores the lives of 19 men, women, and children owned by Washington. It is the site’s attempt to tell the stories of the enslaved at the Virginia plantation—yet Washington’s legacy sits a safe distance away from this narrative, as the framework for his slaveholding is only to provide “insight into George Washington’s evolving opposition to slavery.”

Andrew Jackson’s The Hermitage plantation in Nashville, Tennessee, hardly addresses the legacy of slavery at all. There are no guided slavery tours at the estate and visitors are left to unpack the display, “

These pervasive separations are symptomatic of an issue that historical sites such as presidential plantations face with telling truthful, full-bodied stories about slavery—stories that are integrated, ubiquitous, and inescapable. More often than not, the true history and legacy of slavery takes a back seat to tales of founding-era exceptionalism.

I’ve taken the house tour at Monticello three times in the past three years, and each visit followed a similar pattern: First, Jefferson is glorified for his intellectual curiosity, scientific discoveries, architectural innovations, and avant-garde tendencies. Next, he’s lauded for his role in drafting the Declaration of Independence. There’s an offhand mention of the fact that, in his lifetime, he owned more than 600 slaves.

The tour would then carry on to Martha Jefferson’s sitting room, where their family history is described in definitive and finite terms: “Jefferson was married to Martha for 10 years and fathered six children, two of whom survived. Their names were Mary and Martha.”

After decades of contentious debate surrounding the legitimacy of Hemings’s connection to Jefferson, Monticello has finally acknowledged in unqualified terms that the president was, in fact, the father of Hemings’s offspring. “She was his concubine.” “Sally Hemings had at least six children fathered by Thomas Jefferson.” These are the bold new phrases that the current Hemings exhibit uses to address the relationship between these two American figures.

Monticello first embarked on this truth-telling mission by excavating the experiences of the enslaved people who lived and labored at Monticello, and by seeking to honor those nameless and forgotten souls buried near the site’s current-day visitor parking lot. “The opening of the ‘Life of Sally Hemings’ exhibit and the ‘Getting Word’ oral-history project … is the culmination of decades of research on slavery and the lives of enslaved people at Monticello,” Niya Bates, the public historian of slavery and African American life at the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, told me. “The goal of these new spaces is to not only acknowledge the humanity of the enslaved community, but to tell a more truthful and inclusive history of Monticello, Jefferson, and the founding era in a way that challenges people to think about all of the people that it took to found our country.”

Despite these efforts, separation still persists at Monticello and other historical sites. Of the estimated 450,000 people who visit Jefferson’s mansion each year, only 150,000 take the “Slavery at Monticello” tours. And The Hermitage, Mount Vernon, the Hofwyl-Broadfield plantation in Georgia, and the Colonial Williamsburg historic area, among others, continue to either segregate slavery or ignore it altogether.

It goes without saying that there are tremendous risks involved in telling an integrated story. For one, conservative donors can have huge influence over the way a site is run. Yet despite the challenges, there are a number of presidential plantations, house museums, and historical sites that are making a deep impact on the discussion of slavery by actively integrating the stories of the enslaved.

Back in October 2017, I visited James Madison’s Montpelier, a plantation located approximately 30 miles north of Monticello. At Montpelier, slavery is everywhere. The stories of the enslaved community can be heard in the fields, in the cemetery, in the South Yard slave quarters, and at James and Dolley Madison’s dining-room table. These narratives continue in an exhibit called “The Mere Distinction of Color,” which uses slavery to connect the past to the present.

Last February, Montpelier convened the inaugural National Summit on Teaching Slavery to establish a set of best practices for understanding slavery and its legacies through partnership with descendant communities. I was among the 49 academics, museum professionals, and descendant community members invited to participate in the summit. During the two-day convening, we were asked to put forth a series of recommendations for how to teach the history of slavery at museums and historic sites. We also laid the foundation for a national rubric, which is debuting later this month. “Montpelier is trying to interpret this difficult history of slavery in today’s world, and the people with the greatest stake in that history are descendants,” says Elizabeth Chew, the site’s vice president for museum programs. “To tell the most truthful story, we have to include them.”

Madison’s plantation was purchased by the National Trust for Historic Preservation in 1983. And over time, Montpelier has conducted research to better understand the plantation and the more than 300 enslaved men, women, and children who populated the estate. “This plantation was built with slave labor.” “Slaves overheard conversations about freedom and independence at the dinner table where they served.” “Madison considered slavery an evil and original sin in our country, but never freed any of his slaves.” “He was a lifelong slaveholder.” These were some of the first statements I heard when I visited the Montpelier mansion last year. I listened to stories about Paul Jennings, an enslaved man who served the Madison family. And I also learned about those families torn apart by Dolley Madison.

Of the developments at Montpelier, Chew told me, “An advisory group of descendant community members gave us two pieces of advice: Emphasize the humanity of their ancestors and don’t leave slavery in the past. As a result, we use the faces and voices of the descendants in telling their ancestors’ stories. The exhibition is far more impactful than it would have been if we hadn’t collaborated and listened.”

The summit’s forthcoming “Teaching Slavery” rubric was motivated by a belief that “truthful history can influence a larger public toward reconciliation.” We concluded that the story of slavery and its legacies is best told through historical research, honest interpretation, and relationship building with descendant communities. Creating partnerships with the progeny of enslaved people and recognizing them as stakeholders can only improve an institution’s ability to tell the true story of this nation’s founding. But talking to these families is not enough. It is undermining to incorporate their voices if slavery is still kept at the margins at these sites. The nation’s sordid past must be examined in its entirety in the mansions, cabins, kitchens, basements, fields, and graveyards alike.

Talitha LeFlouria is an associate professor at the University of Virginia, and the author of Chained in Silence: Black Women and Convict Labor in the New South.