Photo: Kiratiana Freelon

It’s Complicated: Why Some Afro-Brazilians Are Willing to Vote for a Racist Presidential Candidate Who’s Calling for More Police Violence.

Last week, Jair Bolsonaro, Brazil’s white, hard-right presidential candidate, received an unexpected American endorsement.

“He sounds like us,” said David Duke, an unabashed white supremacist and former Grand Duke Wizard of the Louisiana Ku Klux Klan. “He is a total European descendant, he looks like any white man in the U.S., in Portugal, Spain, or Germany and France and he is talking about the demographic disaster that exists in Brazil.”

Bolsonaro publicly refused the endorsement, but Daniela Gomes, a Brazilian living in America knows exactly what an endorsement from this American terrorist organization means.

“To me, the KKK represents fear. It’s the fear of what is going to happen to us as black people,” said Gomes, an Afro-Brazilian woman studying for her Ph.D. at the University of Texas. “Bolsonaro and the KKK are linked by their anti-blackness, racism and white supremacy, so Bolsonaro represents that fear, too. Bolsonaro is a return to the past. It’s like going back to a time machine where I can see the future and the past at the same time.”

Gomes has every reason to be scared. Bolsonaro wants to turn the clock back 50 years to a time when most black Brazilians couldn’t read. Black women worked predominantly as domestic servants. Brazilians lived under a military dictatorship subjected to executive decrees that led to the greatest human rights abuses of the 20th century.

Brazilians might elect Jair Bolsonaro, a racist, fascist, white supremacist who wants to fight violence with more violence as their next president. He leads in all polls over Fernando Haddad going into Sunday’s elections. There is fear that a Bolsonaro presidency will not only reverse the advances that Afro-Brazilians have achieved in the last 15 years but also exacerbate a black genocide whose violence disproportionately affects young black men. But this fear isn’t shared by all Afro-Brazilians. At least half of the country’s blacks plan to vote for Bolsonaro because they say he promises to wrangle in Brazil’s rampant crime, promote family values and end corruption.

The support for Bolsonaro is divided among blacks in Brazil. Those who self-identify as Pardo (brown/mixed-race) and Preto (black), make up more than 50 percent of Brazil’s population of 210 million. According to various polls, anywhere from 31 percent to 47 percent of blacks in Brazil intend to vote for Bolsonaro. So does this mean that up to half of Brazil’s blacks might vote for a racist candidate? Yes, but like everything in Brazil, it’s complicated.

***

To understand Bolsonaro’s rise one needs to examine the previous 15 years in Brazil—an era marked by the greatest economic and educational advancement by blacks in the country’s history. When Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva became president in 2003, Brazil entered a golden decade in which its economy expanded by 50 percent. Unlike previous Brazilian governments, Lula’s Workers’ Party (PT) used the extra income to expand education and eradicate extreme poverty. The government revitalized and expanded Bolsa Familia, a social welfare program that decreased extreme poverty by 50 percent. Fernando Haddad, then the education minister, opened 14 new public universities. The Supreme Court approved racial affirmative action in federal higher education institutions. Domestic servants received full workers’ rights by law. All of these advancements disproportionately helped Afro-Brazilians, who have long struggled unsuccessfully to enter the middle and upper classes. The number of blacks in the 1 percent—earning more than $3,000 a month—increased by 60 percent from 11.4 percent to 17.5 percent.

Thâmara Ferreira, 21, knows personally how much Lula’s anti-poverty and education initiatives helped her and her family. Before moving to join her mother in Rio de Janeiro 10 years ago, Ferreira lived in Maranhão, Brazil’s poorest state. She lived with her grandmother and aunt, who cared for five young kids. There was no formal employment to be had. But the family received a small monthly stipend, enough to buy food, as long as all the children attended school.

“Bolsa Familia was very important for me to continue going to school,” Ferreira said. “This small amount of money helped us to survive.”

At the time, Ferreira’s grandmother’s house didn’t even have electricity, but it arrived during the Lula government. She joined her mother in Rio de Janeiro when she was 10. Her mother worked as a domestic servant, so Ferreira didn’t go to a private high school. While she was studying for her college entrance exam, she discovered university affirmative action policies that gave preference to poor and/or black students who studied at public high schools.

In 2015, Ferreira gained acceptance into the state university of Rio de Janeiro, where she studies international relations.

“The social policies of Lula helped me as a child with food and helped me as a teenager to enter university,” said Ferreira, who plans to vote for Haddad.

Bolsa Familia is only 0.05 percent of Brazil’s gross domestic product, but Ferreira’s story proves its impact.

Thâmara Ferreira says she benefitted greatly from the policies of Lula’s Workers’ Party.

Photo: Kiratiana Freelon

These advancements came at the price of corruption. PT achieved these gains through bribing politicians from opposition parties. The Mensalão scandal nearly cost Lula his second term in 2006. This is not to be confused with 2014’s Lava Jato corruption scandal. The Lava Jato scandal revealed that many politicians across a variety of parties, though least of all PT, used Brazil’s state-owned oil company, Petrobras, as their own personal bank. The economy slowed down in 2014 just as Lava Jato erupted. President Dilma Rousseff, Lula’s elected successor, became the fall person. By the time she was ousted in 2016 in a soft coup, the PT had enjoyed 14 years as the main ruling party. But as the Brazilian economy shrank, the country’s bloody violence skyrocketed—61,619 people were murdered in 2016. And a conservative evangelical religious wave, coupled with the austerity program of the interim government, pushed Brazil further right than the days of the dictatorship.

In 2016, the United States elected the racist Donald Trump as president. The election of a white populist candidate promising to “Make America Great Again” set the stage for the ascension of another racist, populist politician—Jair Bolsonaro. Both Trump and Bolsonaro invoke a white nostalgia that terrorizes black people. The good ole’ days for whom?

In April 2017, a Rio Jewish sports and social club welcomed Jair Bolsonaro for a talk in front of 300 members. While 200 people protested his presence outside, inside, Bolsonaro compared the Quilombolas, descendants of African slaves who live in maroon societies, to obese and lazy livestock.

“The lightest Afro-descendant there weighed seven arrobas,” he said, using a weight measurement applied in Brazil exclusively to cattle. “They do nothing. I think they’re useless even for procreation.”

Before Bolsonaro became a candidate for president earlier this year, he was already notorious for his homophobic, sexist and racist behavior. In 2011, pop star Preta Gil asked the military reservist and 28-year fringe politician how he would react if one of his sons fell in love with a black woman. He replied that he would not discuss “promiscuity” with Gil and that he has no fear of a black daughter-in-law because he raised his children right. He said that he would never enter a plane flown by a pilot nor would he undergo the knife of a surgeon who had benefited from affirmative action. He proclaimed he would rather have a dead son than a gay son and even once told a fellow congresswoman that she wasn’t worthy of being raped.

But if that didn’t scare most socially marginalized Brazilians from voting for Bolsonaro, his public security plans for Brazil should. Last year, more than 63,000 people were murdered in the country, three times the number in the United States. Brazil ranks first in the world for murders of LGBTQ people, fifth in femicide, and 74 percent of gun-related deaths are young, black and male.

Bolsonaro has publicly stated: “I will give the police carte blanche to kill; Let’s clog up the prisons with criminals; and police that kill thugs will be decorated.”

So instead of using a two-fingered peace sign, Bolsonaro and his followers use their hands to mimic the shooting of a machine gun. Bolsonaro wants to give police forces the freedom to kill at will without suffering any consequences. Like the United States, there is no hard data on police killings, though it’s estimated that police in Brazil killed more than 5,000 people last year.

“This means that a police can enter a favela, kill whomever he wants, allege that it was a confrontation in which he had to murder 10, 15, 20 people,” said Vítor Coff del Rey, an activist in Rio de Janeiro. “This will victimize even more of the black population who is already the preferred target of the police.”

Gun-control laws prevent the average citizen from owning firearms. So Bolsonaro also wants to make it easier for “good citizens” to carry. His “fight violence with more violence” stance has attracted the support of Brazilians throughout the country who feel that they can’t protect themselves.

***

Brazilians are already suffering the consequences of Bolsonaro’s hateful discourse and penchant for violence. Since October 1, supporters of Bolsonaro have committed more than 100 attacks across the country. Mestre Moa do Katendê—a capoeira master and advocate for Afro-Brazilians—was stabbed to death on October 7 after saying he would not support the hard-right candidate for president, Jair Bolsonaro. Men beat a transsexual woman in the suburbs of Rio de Janeiro. Students in São Paulo mocked a black professor with racial epithets and drew a swastika on the school.

Dressed in the obligatory uniform of yellow and green shirts, thousands of Bolsonaro supporters flocked to Rio de Janeiro’s Copacabana beach last Sunday for one last rally before Election Day, October 28. Attendees shouted chants against corruption and rampant violence, while black street vendors not only sold Brazilian flags but also blue and yellow T-shirts emblazoned with Bolsonaro’s image. Sound trucks blasted Brazilian country music as well as “clean” funk songs that smack-talked jailed ex-president Lula and his Workers’ Party. Most of the crowd was visibly white but there were some Afro-Brazilians. They, as expected, were just as animated as their white counterparts.

Gizele Santana says that the president of Brazil will not govern just for blacks or whites.

Photo: Kiratiana Freelon

With her blue hair, yellow booty shorts, and a green tank top, Gizele Santana looked stylish standing on the side of the rally. But as a dark-skinned black woman, she also stood out against the pale Brazilians who dominated the scene.

“I support Bolsonaro because he has a clean record,” said Santana, who is a technical nurse. Yet, three days prior, a massive slush-fund scandal had rocked the Bolsonaro campaign, revealing that private companies were illegally financing Whatsapp fake news operations estimated to be worth three to four times that of the crimes for which Lula remains jailed.

Santana continued by proudly announcing that she had sent her daughter to a good private school who didn’t need affirmative action to gain admittance into the state university of Rio de Janeiro. When probed as to why she would support a candidate who has said such egregious things about blacks, she brushed it off.

“I don’t think it’s the case that he doesn’t like black people,” she said. “But I still support him because I think it’s a personal choice of his to not like [black people].”

Nicolas Silva plans to vote for Bolsonaro. Photo: Kiratiana Freelon

Nicolas Silva watched the rally with his friends as he wrapped in a massive Brazilian flag. Silva lives in the suburbs of Rio de Janeiro and when he finishes high school, he plans to enter the army. As a 17-year-old, he has the right to vote in Brazil, though it isn’t yet mandatory.

“Bolsonaro has never been imprisoned like other corrupt politicians. I know that he is an honest person,” Silva said. “The 13 years of PT destroyed Brazil. If we get rid of these people, Brazil can breathe. Bolsonaro is the only person that can bring us out of this period.”

Silva also defended Bolsonaro against claims of racism.

“His brother-in-law, Hélio, the big black guy, was elected to Congress with the most votes in the state of Rio de Janeiro. Helio is totally a friend of his,” Silva said. “And as for the black population, I don’t see them protesting his racism.”

Hélio “Negão” “Bolsonaro” is a black military sublieutenant from the suburbs of Rio de Janeiro and, although he was elected with the most votes in the state, he is not Bolsonaro’s brother-in-law. Bolsonaro allowed Hélio to use his last name during the election and it proved fruitful. Hélio is often the only black elected official at Bolsonaro press conferences and events.

Fifty-year-old Mariela Rodrigues attended the rally alone.

“I want a better Brazil with better education, security, and health,” said Rodrigues, who works as a home health-care aide and has suffered three robbery assaults, one with a gun. “Our country is very rich , but the people are in misery.”

The fact that black Brazilians in Rio de Janeiro support Bolsonaro does not surprise Tianna Paschel, author of the book, Becoming Black Political Subjects: Movements and Ethno-Racial Rights in Colombia and Brazil. This especially isn’t surprising for poorer Brazilians.

“Anytime things get unstable economically, they start getting scared,” said Paschel, an assistant professor in African-American studies at the University of Berkeley. “Folks are basically willing to give up some up their freedoms for the sake of security and some promise of economic stability.”

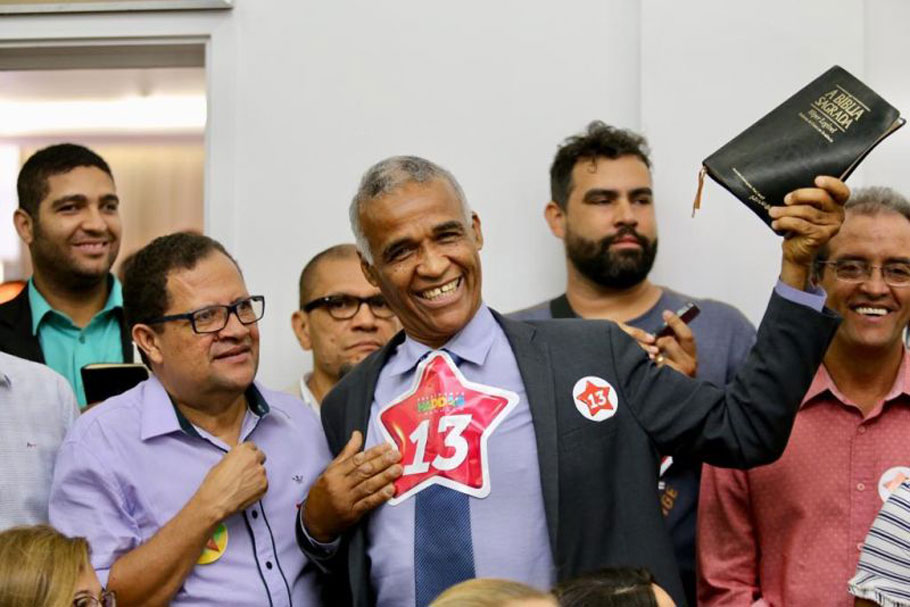

With just a few days until the final vote, there is still a possibility that Bolsonaro supporters can change their minds and vote against a man who promotes blind hate and bloodshed. Evangelical pastor, military police sergeant, self-declared ex-gay and Bahia’s most popular congressional representative, Manoel Isidório de Santana Junior, did exactly this. While holding a thick, black bible, Pastor Sargento Isidório explained to a crowd why he was changing his vote from Bolsonaro to Fernando Haddad.

Pastor Sargento Isidório switched his vote from Bolsonaro to Haddad. Photo: Facebook

“I discovered the danger our country is in when [Bolsonaro] says that police that don’t kill are not police… Violence breeds more violence,” said the black politician. “I can’t blow up my country for hate against the Brazilian people. And this is why I am voting for Professor Haddad.”

Kiratiana is a journalist based in Rio de Janeiro. She’s currently writing a black travel and culture guide to Rio de Janeiro.