This op-ed argues that Black labor organizers have long recognized that better conditions for Black and brown workers result in better conditions for everyone.

By Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman and Katie Camacho Orona, Teen Vogue —

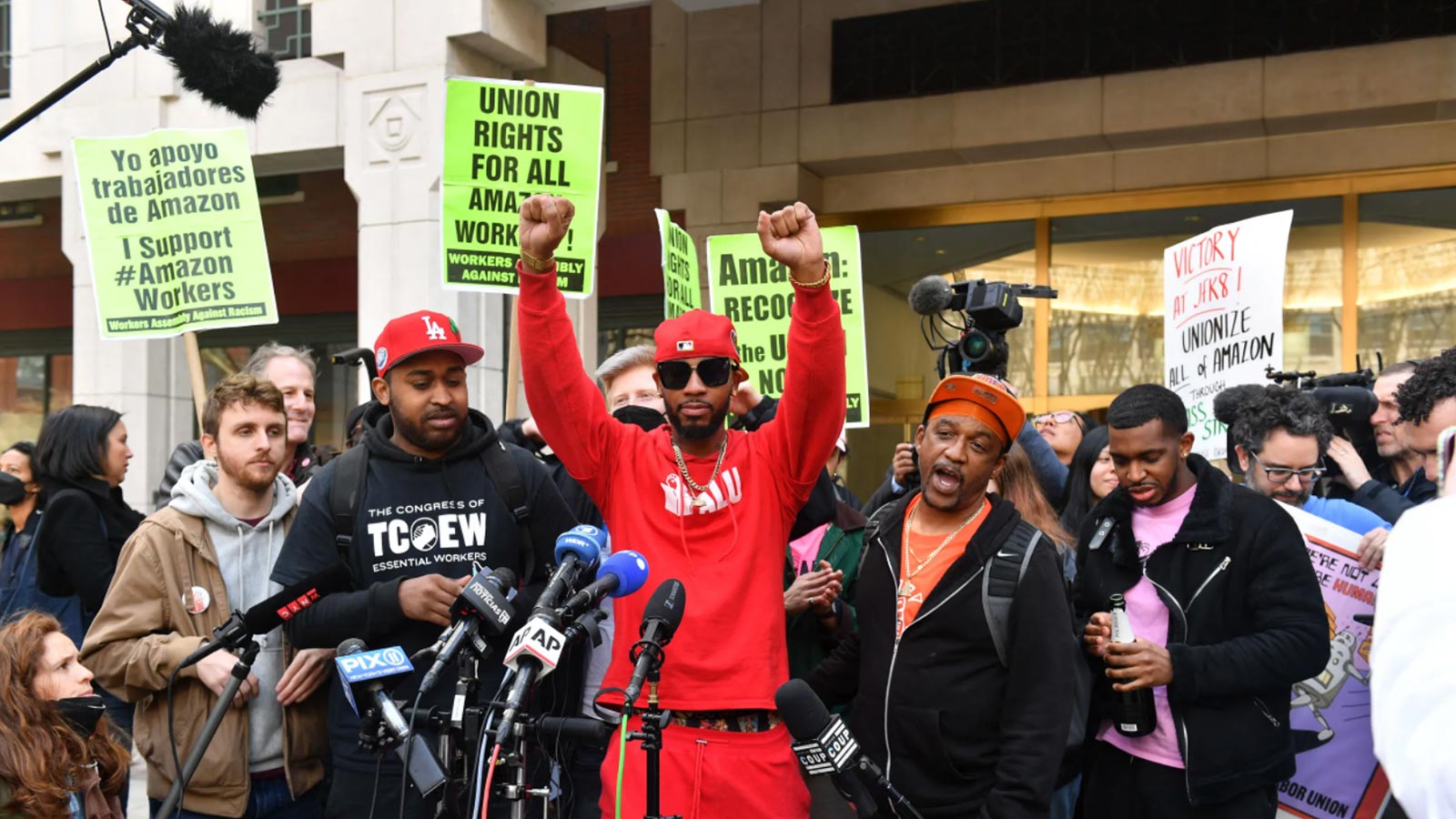

On April 1, 2022, Jeff Bezos received some news that he wished was an April Fools’ joke: Amazon warehouse workers in Staten Island won their vote to create a union, beating the odds and making history in the process. The face of the “Shut Down Amazon” movement, a working-class Black man named Christian Smalls, is building on the legacy of Black labor leaders whose efforts define generations.

While there are countless articles profiling Smalls, few have acknowledged the long history of Black labor leaders taking the helm of workers’ rights movements. Smalls, who was subjected to a smear campaign by Amazon and dismissed as “not smart or articulate” by company leaders, is reminiscent of a lineage of Black American labor organizers and scholars who have always recognized the liberation of all workers begins with the Black worker.

African Americans have participated in labor activity since before the Civil War, as documented by the National Archives. Like many American institutions in the century following that war, organized labor often excluded or marginalized Black people, despite workers’ shared interest in advocating for better conditions, especially in occupations that failed to dignify their labor.

During The Great Migration of 1916 to 1960, millions of African Americans relocated from the South to the Northeast and Midwest in pursuit of employment in industries including steel, automotive, shipbuilding, and meatpacking. Yet these gains occurred alongside the government’s refusal to extend rights to many workers of color. In 1938, Congress passed the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), a landmark piece of legislation enshrining protections for workers, yet it excluded domestic, agricultural, and tipped workers, purposefully denying many Black and brown people the same rights and protections given to white workers. Additionally, according to the National Employment Law Project, “Nearly half of all Black men, Mexican American men, and Native American men and women…were excluded from Social Security, unemployment insurance, and the right to organize” in the National Labor Relations Act of 1935. The effects of this exclusion fell disproportionately on Black women because of their concentration in agriculture and domestic work. Perhaps this is why the first Black woman economist in the U.S., Dr. Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander, focused her dissertation on the economic outcomes of families that participated in The Great Migration. She also advocated for recentering the economy on Black women workers as one way to promote economic growth and progress for the Black community.

Like Alexander, Smalls deeply understands that improving labor conditions for Black workers could and would unlock more equitable outcomes for all. Consider that in 2019, at nearly every educational level, Black workers were twice as likely to be unemployed. Historically, on average, the Black unemployment rate changes by 1.7 percentage points for every 1 percentage point of change in the national unemployment rate. Given well-documented and persistent patterns of racial inequality in employment, when the unemployment rate soared during the early months of the COVID pandemic, Black workers, and especially Black women, were disproportionately affected. And those workers have experienced the slowest economic recovery.

Chris Smalls holds a sign during a protest outside an Amazon facility on Staten Island on May 1, 2020, after he was fired by the company.(Bloomberg)

In 2020, Amazon’s own demographic data also revealed that nearly 63% of its warehouse and call-center workers were Black, Latino, Native American, or multiracial, compared to approximately 21% of its corporate workforce. The Pew Research Center found that the majority of jobs that are being lost amid the pandemic are concentrated in the service sector where, in 2018, Black or African American workers and Latinos were overrepresented. Ironically, these workers are considered unskilled and, to some, unworthy of a living wage, health care, and/or financial security. Yet, unprotected workers in these jobs are coming together to fight for better wages and working conditions as we have seen at Amazon.

This is why it matters that Christian Smalls is a leader of a historic union-organizing movement: His persistence and frankly unapologetic Blackness honor the past, present, and future of workers who are fighting for their dignity. Smalls has remained humble about his role in the collective organizing drive, telling Labor Notes, “It’s not my union. It’s the people’s union.” But it’s worth noting the outsized role he played in the successful campaign because it was Amazon’s general counsel, David Zapolsky, who suggested that “[making Chris Smalls] the most interesting part of the story and, if possible, making him the face of the entire union-organizing movement” would kill the movement itself.

No one can deny that ordinary people taking on Big Tech is the epitome of fighting the power — a power that made billions during the pandemic shares little to nothing with frontline workers and fails to correct horrific working conditions. The anti-Blackness built into so much of our technology makes this win, spearheaded by a working-class Black man, that much more symbolic.

Source: Teen Vogue

Featured image: Amazon union’s Chris Smalls. (Photo by Andrea Renault)