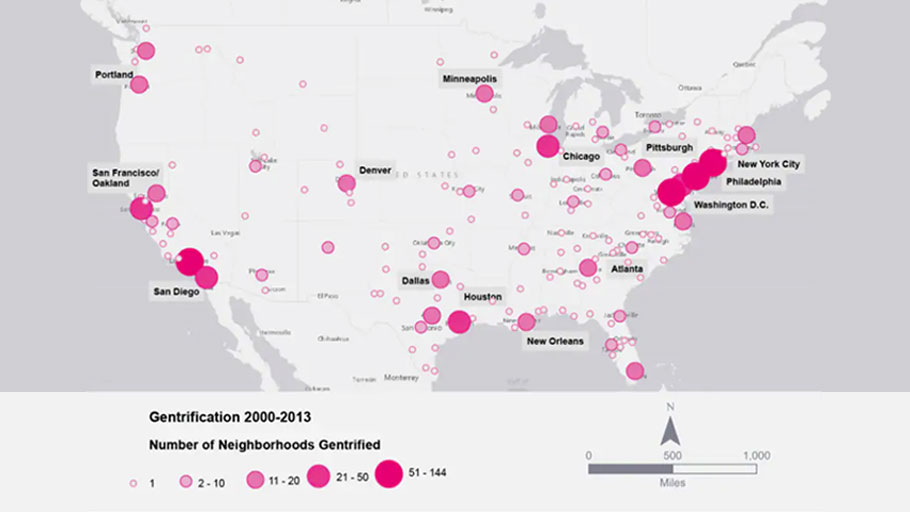

A study by the National Community Reinvestment Coalition found that coastal cities had the largest number of neighborhoods that were gentrified from 2000 to 2013.

More than 20,000 African American residents were displaced from low-income neighborhoods from 2000 to 2013, researchers say.

By Katherine Shaver, Washington Post —

About 40 percent of the District’s lower-income neighborhoods experienced gentrification between 2000 and 2013, giving the city the greatest “intensity of gentrification” of any in the country, according to a study released Tuesday by the National Community Reinvestment Coalition.

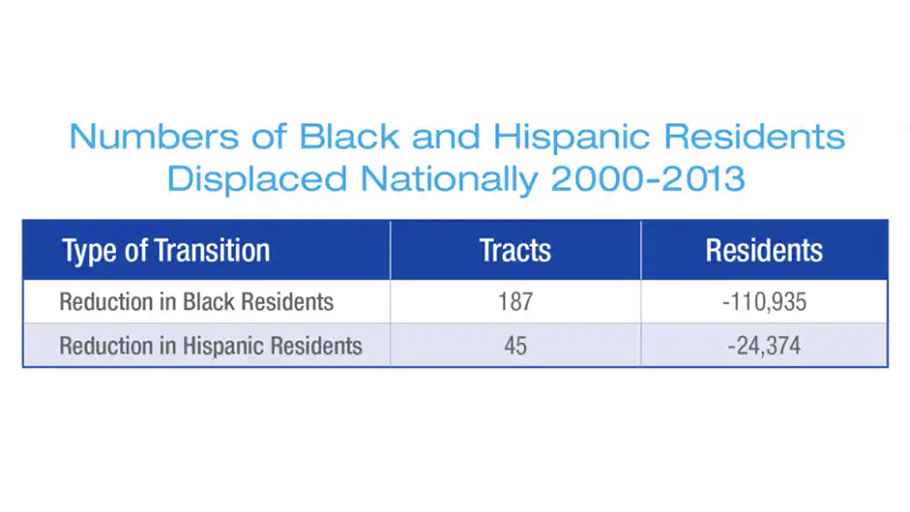

The District also saw the most African American residents — more than 20,000 — displaced from their neighborhoods during that time, mostly by affluent, white newcomers, researchers said. The District and Philadelphia were most “notable” for displacements of black residents, while Denver and Austin had the most Hispanic residents move. Nationwide, nearly 111,000 African Americans and more than 24,000 Hispanics moved out of gentrifying neighborhoods, the study found.

Sixty-two 62 lower-income census tracts in the District gentrified between 2000 and 2013, putting the city third behind New York and Los Angeles for the highest number of neighborhoods that had transformed. The District ranked first in “intensity of gentrification,” on the basis of the percentage of lower-income neighborhoods that experienced gentrification.

Because of the District’s intensity ranking, “you feel it and you see it,” said Jesse Van Tol, chief executive of the NCRC, a research and advocacy coalition of 600 community organizations that promote economic and racial justice. “It’s the visibility and the pace of it.”

A National Community Reinvestment Coalition study found “cultural displacement” because of gentrification in neighborhoods nationwide. In the District, more than 20,000 black residents were displaced. Source: National Community Reinvestment Coalition

The study defines gentrification as occurring when “an influx of investment and changes to the built environment lead to rising home values, family incomes and educational levels of residents.” It defines “cultural displacement” as instances when “minority areas see a rapid decline in their numbers as affluent, white gentrifiers replace the incumbent residents.”

Researchers examined U.S. census tracts that, in 2000, were in the lower 40th percentile for median home values and household incomes in their metropolitan areas.

Van Tol said gentrification has followed a national move back to cities, particularly among affluent workers. The District drew many during the Great Recession, when the city’s economy and job markets were more stable than others. Meanwhile, the amount of affordable housing has lagged, even amid new residential development.

Many residents can rattle off the D.C. neighborhoods that have undergone rapid economic change, including Petworth, Mount Pleasant, Brookland, and the U and 14th street corridors.

Gentrification can benefit areas because it signals economic investment, Van Tol said. The problem comes, he said, when longtime residents are pushed out as rents and property taxes rise, leaving them unable to benefit from the improvements. Activists also are concerned about the culture that can leave with a neighborhood’s longtime residents. Van Tol recalled the 2015 closing of the popular Jamaican restaurant Sweet Mango Cafe in Petworth and the end of the neighborhood’s annual Caribbean parade.

“I think the loss of these cultural institutions has really changed the identity of neighborhoods in a way that might be unwelcome by the people who have lived there,” Van Tol said.

Van Tol said he was surprised by the finding that gentrification was rare in small and medium cities in the country’s interior. Nationally, the study found, nearly half of all gentrified neighborhoods were in seven cities: the District, New York, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Baltimore, San Diego and Chicago.

In an essay accompanying the study, Sabiyha Prince of Empower DC said the city “rolled out the proverbial red carpet” for tens of thousands of new residents in the past five years. But the new dog parks, bike lanes, condominiums and pricey restaurants that followed, she said, are not viewed as improvements by long-term residents, who can feel isolated because of losing neighbors, social networks and local businesses. Prince, an anthropologist, said longtime Washingtonians tell stories of “alienation and vulnerability in the nation’s capital.”

“The hopes, dreams and needs of low-income and working class residents — which include truly affordable housing, safe and reliable child care, food justice, the ability to attend houses of worship and the unencumbered use of public spaces — do not diligently appear on the local legislative body’s list of pending priorities,” Prince wrote.

Gentrification is also a factor in the city’s lack of affordable housing, residents say.

A 2017 Washington Post poll found that three-quarters of Washingtonians, including 78 percent of those who moved to the District in the past 15 years with incomes of at least $150,000 per year, said that new, high-income residents were a “major reason” for the shortage of affordable housing in the District.

Overall, the poll found, two-thirds of D.C. residents — including larger shares of whites (88 percent) and those making more than $100,000 (86 percent) — said redevelopment was “mainly good.”

The researchers recommended policies that they say promote investment in neighborhoods while ensuring that existing residents can afford to stay to benefit from it. Those include mandating that renters have the right of first refusal to buy units when apartment buildings are converted to condominiums, coupled with financing programs to help low-income and first-time buyers.

Van Tol said he was most surprised by researchers’ finding many areas in the United States where gentrification didn’t necessarily result in residents being displaced. Those tended to be areas with more homeowners, who were less vulnerable to being pushed out by rapid rent increases as property values rose. Finding ways for gentrification to proceed without forcing out longtime residents is an area ripe for more study, he said.

“I’m not anti-gentrification,” Van Tol said. “I’m anti-displacement. Investing in these neighborhoods is very much needed.”

Emily Guskin contributed to this report.