As the world ignores the ignominious 500th anniversary of the buying and selling of slaves between Africa and the Americas, historians uncover its first horrific voyages.

By David Keys, The Independent —

Almost completely ignored by the modern world, this month marks the 500th anniversary of one of history’s most tragic and significant events – the birth of the Africa to America transatlantic slave trade. New discoveries are now revealing the details of the trade’s first horrific voyages.

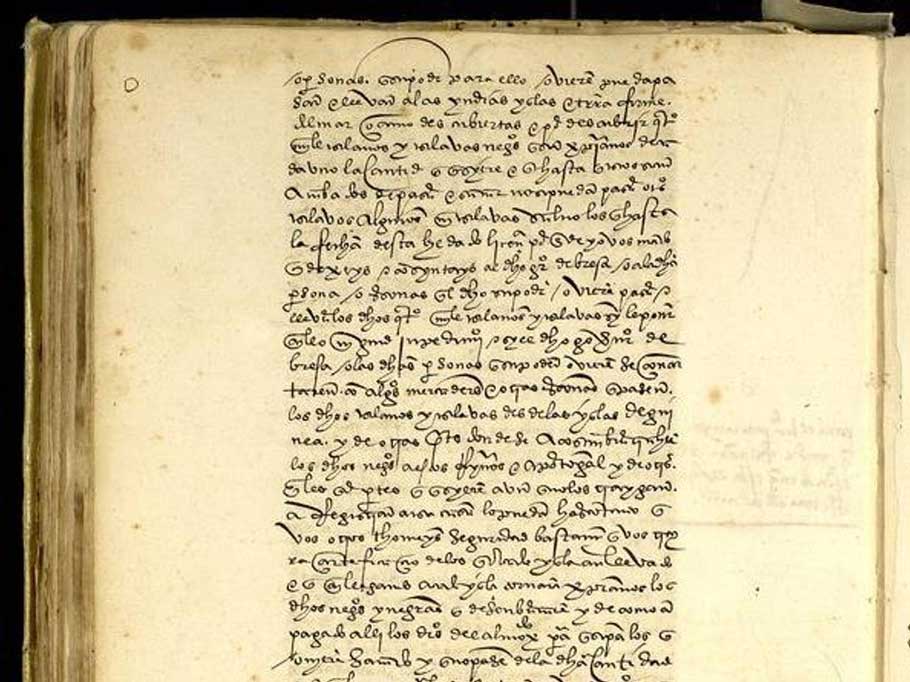

Exactly five centuries ago – on 18 August 1518 (28 August 1518, if they had been using our modern Gregorian calendar) – the King of Spain, Charles I, issued a charter authorising the transportation of slaves direct from Africa to the Americas. Up until that point (since at least 1510), African slaves had usually been transported to Spain or Portugal and had then been transhipped to the Caribbean.

Charles’s decision to create a direct, more economically viable Africa to America slave trade fundamentally changed the nature and scale of this terrible human trafficking industry. Over the subsequent 350 years, at least 10.7 million black Africans were transported between the two continents. A further 1.8 million died en route.

This month’s quincentenary is of a tragic event that caused untold suffering and still today leaves a legacy of poverty, racism, inequality and elite wealth across four continents. But it also quite literally changed the world and still geopolitically, socially, economically and culturally continues to shape it even today – and yet the anniversary has been almost completely ignored.

“There has been a general failure by most historians and others to fully appreciate the huge significance of August 1518 in the story of the transatlantic slave trade,” said one of Britain’s leading slavery historians, Professor David Richardson of the University of Hull’s Wilberforce Institute for the Study of Slavery and Emancipation.

The sad reality is that there currently are only two or three academics worldwide studying the origins of the transatlantic slave trade – and much of our knowledge about it has only been discovered over the past three years.

“The discoveries we’ve made are transforming our understanding of the very beginnings of the transatlantic slave trade. Remarkably, up till now, it’s been a shockingly understudied area,” said Professor David Wheat of Michigan State University, a historian who has been closely involved in the groundbreaking research.

In the August 1518 charter, the Spanish king gave one of his top council of state members, Lorenzo de Gorrevod, permission to transport “four thousand negro slaves both male and female” to “the [West] Indies, the [Caribbean] islands and the [American] mainland of the [Atlantic] ocean sea, already discovered or to be discovered”, by ship “direct from the [West African] isles of Guinea and other regions from which they are wont to bring the said negros”.

Although the charter has been known to historians for at least the past 100 years, nobody until recently knew whether the authorised voyages had ever taken place.

The royal document which launched the Africa to Americas transatlantic slave trade exactly 500 years ago. Issued by the Spanish King, Charles I, its horrific consequences lasted for 350 years (Ministry of Culture and Sports of the Government of Spain/Archivo General de Indias)

Now new as-yet-unpublished research shows that those royally sanctioned operations did indeed take place with some of the earliest ones occurring in 1519, 1520, May 1521 and October 1521.

These four voyages (all discovered by American historians over the past three years) were from a Portuguese trading station called Arguim (a tiny island off the coast of what is now northern Mauritania) to Puerto Rico in the Caribbean. The first three carried at least 60, 54 and 79 slaves respectively – but it is likely that there were other voyages from Arguim to Hispaniola (modern Haiti and Dominican Republic). The discoveries were made in Spanish archives by two historians – Dr Wheat, of Michigan State, and Dr Marc Eagle, of Western Kentucky University.

It is likely that at least the 1520 voyage – and conceivably also the 1519 one – was by a Portuguese or Spanish caravel called the Santa Maria de la Luz, captained by a mariner called Francisco (or Fernando) de Rosa. The new research also shows that one of the 1521 voyages was by another caravel, the San Miguel, captained by a (probably Basque) sailor called Martin de Urquica, who was acting on behalf of two prominent Seville-based businessmen, Juan Hernandez de Castro and Gaspar Centurion.

The Arguim story had had its genesis more than 70 years earlier when, in 1445, the Portuguese established that trading post so that Portugal could acquire cheaper supplies of gold, gum Arabic and slaves.

By 1455, up to 800 slaves a year were being purchased there and then shipped back to Portugal.

Arguim island was just offshore from a probable coastal slave trade route between a series of slave-trading West African states, who almost certainly sold prisoners-of-war as slaves, and the Arab states of North Africa.

In that sense, the direct transatlantic slave trade that began in 1518/1519 was a by-product of the already long-established Arab slave trade.

However, any reliance on buying slaves from Arab slave trade operations did not last long, for in (or by) 1522, some 2,000 miles southeast of Arguim, direct slave voyages started between the island of Sao Tome off the northwest coast of central Africa and Puerto Rico and probably other Caribbean ports.

Academic research shows that this 1522 voyage carried no fewer than 139 slaves. Another voyage in 1524, discovered in 2016, carried just 18 – plus lots of other non-human merchandise. But other mostly recently discovered voyages in 1527, 1529 and 1530 carried 257, 248 and 231 slaves respectively. On average, therefore, each early voyage from Sao Tome carried much greater numbers of slaves than the ones from Arguim. It’s also likely that there were many other slave voyages between 1518 and 1530 which still await discovery by archival researchers.

There were also at least six early slave voyages from the Cape Verde Islands off the West African coast to the Caribbean between 1518 and 1530, laden with Black African captives acquired by Cape Verdean slave traders mainly from local African rulers and traders in what is now Senegal, Gambia and Guinea-Bissau, Guinea and Sierra Leone.

But, apart from the Spanish king himself, who were the people who launched the direct transatlantic slave trade from Africa to the Caribbean exactly 500 years ago?

The most senior was the man Charles awarded the slave trade charter to in August 1518. He was Laurent de Gouvenot (Lorenzo de Gorrevod in Spanish) – an aristocrat in the Flemish court and member of the Spanish king’s council of state (Flanders, predominantly the northern part of modern Belgium, was part of the Burgundian Netherlands, ruled by Charles).

Portrait of Charles I of Spain, ruler of the Holy Roman Empire (Wikimedia)

But, for Laurent, the charter was simply a licence from an old chum to make money without actually doing the appalling dirty work himself.

As he was specifically allowed to by the charter, he subcontracted the operations to Juan Lopez de Recalde, the treasurer of the Spanish government agency with responsibility for all Caribbean matters, who in turn sold the rights to transport 3,000 of the 4,000 slaves to a Seville-based Genoese merchant, Agostin de Vivaldi, and his Castilian colleague, Fernando Vazquez, and the right to carry the remaining thousand slaves to another Genoese merchant, Domingo de Fornari.

Vivaldi and Vazquez then (at a profit) resold the rights to transport their 3,000 slaves to two well connected Castilian merchants, Juan de la Torre and Juan Fernandez de Castro, and to a famous Seville-based Genoese banker, Gaspar Centurion, who, along with Fornari, subcontracted the work directly or indirectly to various ships’ captains.

All these businessmen had substantial mercantile experience – and Fornari came from a slave-trading family with a long experience of human trafficking in the Eastern Mediterranean.

At least four voyages from Arguin to Puerto Rico were organised and carried out between 1519-1521. It is likely that Vivaldo and Fornet (still probably acting on the basis of Lorenzo de Gorrevod’s charter) then, after 1521, hired captains to operate from Sao Tome to Puerto Rico. It is perhaps significant that the first Sao Tome-originating slave voyage to the Caribbean took place in 1522 – the year that the Portuguese crown (under the newly enthroned very pro-Spanish Portuguese king, John III) assumed direct control over Sao Tome. This implies that the Spanish and Portuguese crowns may well have been working in close cooperation in the early development of the transatlantic slave trade.

The trade was a catastrophe for Africa. The Arab slave trade had already had a terrible impact on the continent – but European demand for slave labour in their embryonic New World empires worsened the situation substantially. Although many of the slaves for the Arab and transatlantic markets were captured and/or enslaved and sold by African rulers, the European slave traders massively expanded demand – and consequently, in the end, triggered a whole series of terrible intra-African tribal wars.

For, by around the mid-16th century, in order to satisfy European/New World demand, African slave raiders needed more captives to sell as slaves to the Europeans – and that necessitated starting and expanding more raids (and, subsequently, wars) to obtain them. The issuing of the royal charter 500 years ago this month not only led to the kidnapping of millions of people and a lifetime of subjugation and pain for them, but also led to the political and military destabilisation of large swathes of an entire continent.

But this African catastrophe was linked to another terrible human disaster on the American side of the Atlantic, the sheer scale of which is only now being revealed by archaeology. For the main reason that the Europeans needed African slaves to be shipped to the Caribbean was because the early Spanish colonisation of that region had led to the deaths of up to three million local Caribbean Indians, many of whom the Spanish had already de facto enslaved and had intended to be their local workforce.

When Columbus had discovered Hispaniola in 1492, the island had probably had a population of at least two million. By 1517, this had been reduced by at least 80 per cent – due to European-introduced epidemics (the Indians had no immunity), warfare, massacres, starvation and executions. Many of the surviving Indians had also fled into Hispaniola’s mountainous interior where they were beyond the reach of the Spanish state. Ongoing archaeological investigations on the island are only now revealing the sheer scale of its pre-Columbian population.

The reality was that, by 1514, according to a government census, there were only 26,000 Indians left under Spanish control – and the Spanish feared that number would further reduce. It was this population collapse and the fear that it would continue that appears to have forced the Spanish king to, for the first time, authorise direct slave shipments from Africa to the Americas. Spain was desperate to ensure that its royal goldmines and agricultural estates in Hispaniola and its economic projects on the other Caribbean islands would not founder for lack of manpower.

Indeed, just a few months after Charles had issued his 1518 slave trade charter, a majority (perhaps around two-thirds) of all the surviving Indian workers in Hispaniola and Puerto Rico perished in the New World’s very first smallpox epidemic.

The year the direct Africa to Americas slave trade was initiated by royal charter, 1518 is one of the most significant dates in the whole of human history. But, apart from this article, the anniversary has been largely forgotten.

The relative lack of academic attention partly explains the silence.

But an even more significant factor is the way in which Spain and Portugal have had relatively little interest in their respective yet crucial roles in the history of the transatlantic slave trade. What’s more, although Britain and the US have long been very interested in British and US slave trade-related history, they have not shown similar interest in the preceding Portuguese and Spanish slave trades.

Additionally, governments and organisations worldwide have tended to favour commemorating the slave revolts and abolitionist movements which combined to end the slave trade, rather than the more historically distant and politically less comfortable story of how it all began.

Sadly history’s lessons of how things go wrong are at least equally as valuable as the decidedly more inspirational stories of how things were, at least partially, put right.