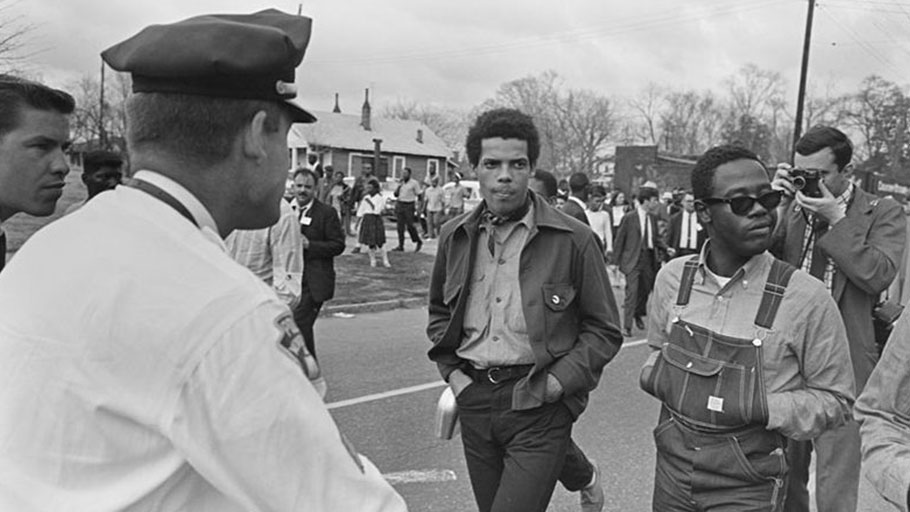

SNCC protesters march in Montgomery, 1965. Photo: Library of Congress, Glen Pearcy Collection.

By Ashley Farmer, Black Perspectives —

“Learn from the Past, Organize the Future, Make Democracy Work.” This is the mission statement that greets visitors at the SNCC Digital Gateway—a wide-ranging, collaborative website that documents and animates the history of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Founded in April 1960 under the guidance of veteran activist Ella Baker, SNCC became a leading civil rights organization due to countless young organizers who engaged in voter registration, political education, and direct action. The SNCC Digital Gateway chronicles the rise of the organization, as well as its major protests, local leaders, and evolving ideological framework. The site offers an unparalleled look into SNCC’s ideological and organizational history and is a brilliant model of democratic, digital engagement.

Learning from the Past

At its founding, SNCC organizers looked to previous leaders, organizers, and organizations to formulate their activist strategies. The Digital Gateway offers the opportunity for visitors to do the same by familiarizing guests with the people, places, and events that comprised SNCC. When guests visit the “People” section, they will learn more about the mentors, organizers, and administrators that helped create and sustain SNCC. The site creators foreground the work of well-known organizers such as Bernice Johnson Reagon, but they also detail the work of lesser-known activists like Annette Jones. Perhaps most impressive is the list of Freedom Summer Volunteers who took part in the historic 10-week program in 1964. Freedom Summer brought student volunteers to Mississippi to engage in widespread Black voter registration, develop freedom schools, and support political and civic literacy. The sheer number of names and organizations compiled attest to the enormity of the project and how young people fundamentally changed the definition and scope of democratic engagement in the late twentieth century.

Visitors can ideologically, visually, and audibly contextualize individual activists via the “Timeline” section of the site. In this section, site collaborators divided SNCC’s history into five periods in order to highlight the different organizational and ideological phases of the group. The timeline begins with “SNCC Origins and Founding,” which spans from 1943 to 1960. It then progresses through “Direct Action to Voter Registration” (1960-1962) to detail SNCC’s turn to Freedom Parties (1962-1965), and eventually, Black Power (1965-1969). The creators conclude the timeline with the “1968-Present” section. Here, the authors show how former SNCC workers still collaborate with the movement—most notably by endorsing the Movement for Black Lives platform in 2016.

The “Our Voices” and “Inside SNCC” sections complement this extensive timeline. Viewers interested in hearing from volunteers about the origins of SNCC, the rise of Black Power, women’s experiences, or the role of music in political organizing can hear or watch SNCC workers talk about these topics. Those who are curious about the internal workings of SNCC can learn more about its internal culture, the national office, the communications department, and even the Sojourner Motor Fleet—SNCC’s transportation company used to “keep its staff mobile.” More than simply a commemoration of the group, these dynamic content sections offer a nuanced look at SNCC activists’ changing political and ideological positions and account for the personal, political, and ideological fissures that developed within and outside of the group.

Organizing for the Future

One of SNCC’s core mantras was mentor Ella Baker’s claim that “strong people don’t need strong leaders.” SNCC Digital Gateway creators are dedicated to this philosophy for the present and future. To that end, the site includes two sections designed to empower contemporary visitors to organize in their own communities. The “Today” section connects SNCC’s previous activism with today’s protest efforts. Readers will find a series of questions such as “what unfinished business are you trying to address?”, “which strategies and tactics are relevant today?”, and “how do you organize a meeting or a demonstration?” that function as a step-by-step organizing guide. Visitors can then go to the “Resources” tab, which includes videos of former SNCC members detailing how their organizing, SNCC’s democratic structure, and its community-based ideals can be applied today.

Making Democracy Work

Ultimately, the site is democratic in its construction, curation, and circulation. Students of all levels, professors, and former SNCC organizers have collectively created a digital space that models how to learn from the past, organize today, and create inclusive communities in the future. The SNCC Digital Gateway illustrates how we can democratically and collaboratively research and build archives that break down imagined borders between academy and layperson, student and teacher, activist and ideologue. As a free, open-access site that includes scores of primary documents, interviews, and audio and visual files, the site is also a model of collaborative curation and democratic circulation. Whether one is familiar with SNCC or new to the beloved community, they will find new information or insights that will alter their thinking about past and present activism.

Many of us instinctually know that the world can be a better place. Yet, we often feel removed from historical examples of how everyday people nurtured this feeling into political action. More expansive, dynamic, accessible histories like the SNCC Digital Gateway transform how we remember, understand, and conceptualize change, renewing our hope for the future and reinvigorating our commitment to making democracy work.

*The SNCC Digital Gateway is a collaboration between the SNCC Legacy Project, the Duke University Libraries, and the Center for Documentary Studies.