Three new histories of British colonialism and slavery – by Vincent Brown, Thomas Harding and Kojo Koram – reveal the empire’s corrosive effects on today’s politics.

By Laleh Khalili, New Statesman —

When he was not trying to sweep slavery and colonialism under the rug – lest a whisper of reparations arises – the former UK culture secretary Oliver Dowden wanted you to believe that it was in the gift of the British to bestow liberty on the world. The official mythology has morally superior Englishmen abolishing slavery before anyone else and at their own whim; and, when they eventually grant independence to their former colonies, leaving behind orderly societies with railways and parliaments. Voluminous research over the past 100 years has debunked this self-flattering distortion, showing that the transformation of this system of exploitation was driven not by the enlightened benevolence of colonial elites, but sustained revolt by the enslaved and the colonised themselves. Meanwhile, thousands of personal stories, literary accounts and scholarly works have exposed the ways empire and colonialism were devastating not only to the colonies, but to life, law and politics in Britain.

Three recent history books are worthy additions to this body of literature. Vincent Brown’s Tacky’s Revolt and Thomas Harding’s White Debt recount two slave rebellions in former British territories on either side of the more prominent Haitian revolution against French colonial rule (1791-1804). Tacky’s Revolt, named after one of the leaders of the insurrection, is a virtuosic account of an uprising (or what Brown terms a “slave war”) in Jamaica in 1760, while White Debt weaves together the story of a slave revolt in Demerara (today’s Guyana) in 1823 with reflections on the contemporary legacy of slavery in Britain. Kojo Koram’s Uncommon Wealth similarly explores the ricocheting effects of colonialism in Britain, tracing the role of empire – and its disintegration – in the rise of contemporary austerity, inequality, poverty, brutality, corruption, and the cartoon sovereignty of Brexit.

The insistence, against colonial powers’ self-mythologising, that the abolition of slavery was the result of enslaved Africans’ self-emancipatory revolts has venerable progenitors, with the Trinidadian author and militant CLR James’s ground-breaking The Black Jacobins (first published in 1938) and the American historian Julius S Scott’s The Common Wind (published in 2018 but circulating as a photocopied PhD dissertation since 1986) among the most influential.

From the beginning of the transportation of enslaved Africans in the 16th century to work the plantations and mines of the New World, the captives had refused their bondage. The Haitian revolution was the final instalment in a triptych of revolutions – the American colonies’ war of independence against Britain, and the overthrow of the French ancien régime – that roiled the Atlantic world in the closing decades of the 18th century.

The revolution of Saint-Domingue – Haiti’s name before independence – began in August 1791 when, amid a fierce tropical storm, thousands of enslaved men and women rose in revolt. Over the next 13 years, successive waves of insurrection eroded the power of the French colonists and led not only to the independence of Haiti in 1804, but to the abolition of slavery in 1833. The revolution was led, CLR James writes, by a “line of great leaders whom the slaves were to throw up in such profusion and rapidity”, from Boukman the vodou high priest and Romaine-la-Prophétesse who led the 1791 uprisings, to Toussaint Louverture, Henri Christophe and Jean-Jacques Dessaline who commanded formal armies of free people of colour and self-liberated former slaves to resist Napoleon’s onslaught. They were supported by Polish soldiers who had been sent by Napoleon to suppress the insurrection, but who joined the revolutionaries in solidarity against slavery.

At various stages of the Haitian revolution, the British worked to weaken the hand of the French but also to defend slavery, lest the revolt circulate to their plantations in the Caribbean. But circulate it did. The Common Wind tells the story of the news of the revolution travelling throughout the Black Atlantic, carried by sailors, deserting soldiers, fugitive slaves, free men and women of colour, and enslaved Africans who were traded onwards or travelled with their proprietors between Caribbean islands and the mainland. In a feat of archival pyrotechnics, Scott showed how these mobile people and the news and rumours they carried with them perturbed officials who correctly calculated that this mobility threatened the ruling plantocracy.

Tacky’s Revolt, which has won numerous awards, is a revelation, and a true heir to The Black Jacobins and The Common Wind. If James and Scott insisted on the politicalnous of the Haitian revolutionaries, Brown’s textured and lively account of the Jamaican rebels who preceded them highlights the enslaved Africans’ military and strategic skills and experience, gained in warfare in their African homelands. The 1760-61 uprisings in Jamaica were in part extensions of wars in West Africa; their leaders had been experienced combatants and commanders captured and sold on to slavers for transportation to the Caribbean. The plantation owners in Jamaica mobilised a force of “soldiers, sailors, militia and maroons” who pursued the rebels into the forests and mountains. When insurrectionists were captured, they were executed on the spot or driven to towns for torture, trial and punishment. Some planters wanted to see all rebels executed; others wanted their “property” restored. In the end, the British government compensated the planters up to £40 (about £1,500 today) for every rebel that was put to death.

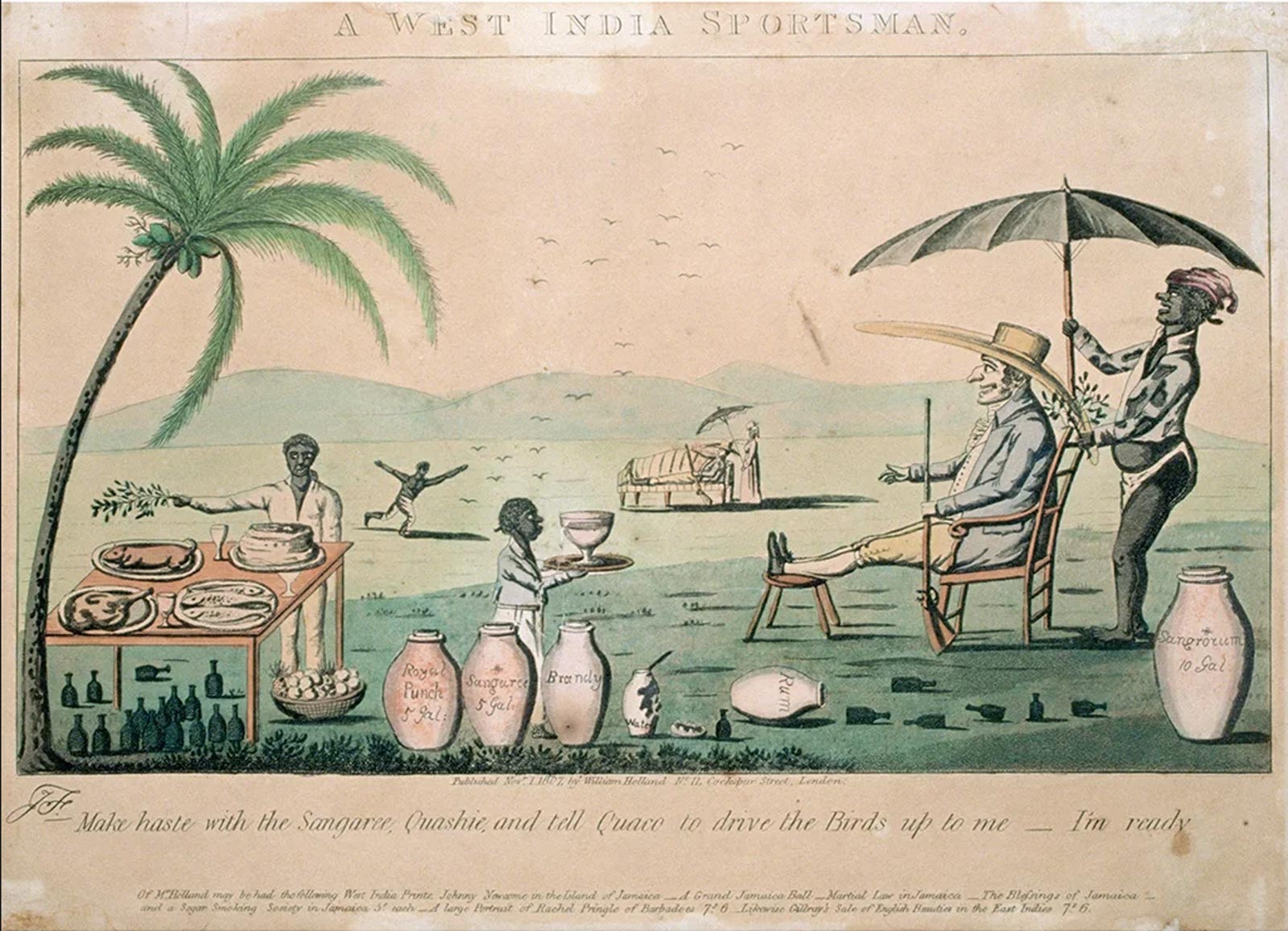

19th-Century cartoon satirizing colonial rule in Jamaica. Photo by Bojan Brecelj/Corbis via Getty Images

Brown shows the expansion of plantation capitalism working hand in hand with the political economy of warfare in Africa and of exploitation and brutality in the New World. Through prodigious and imaginative work with the archives, or, rather, with their absences – namely, of the voices of the enslaved – Brown shows that, although slavers tried to unmoor the enslaved from their homes and communities, language and culture and sense of self, the connections between various African communities and the diaspora endured despite the violence of the plantation regime.

Although the revolts were brutally defeated and many of their leaders executed or sold on to other islands, the Jamaican uprising discernibly influenced the course of history. On the one hand, in response, the British tightened London’s control over the colonies and the planters, leading to a backlash among the colonists in continental America who rebelled a mere 15 years later. But the insurrection also led to the diffusion of revolutionary fervour, rumours and strategies among the African diaspora in the Americas. One of the punishments used against the African-Jamaican revolutionaries was to transport them away from Jamaica, bringing with them news of the 1760-61 slave wars. Many Jamaican captives and exiles ended up in Haiti, perhaps including Boukman, the oracle who led the first wave of revolts in the Haitian revolution.

The Haitian revolution was a crucial victory in a chain of slave revolts in the Americas that led to the abrogation of slavery, and was a hinge event between the Jamaican uprising and the 1823 rebellion in Demerara chronicled by Harding in White Debt. The Demerara insurrectionists had probably heard the rumours about Haiti; the planters and colonial officials in London certainly fretted about the possibility – an 1804 editorial in the Times worried that the revolution in Haiti “may afford an example too encouraging to the Negroes in our plantations”.

The Demerara revolt occurred in the period between Britain’s banning of the slave trade in 1807 and the abolition of slavery 26 years later. While the British may have patted themselves on the back for hobbling the trade in slaves to their imperial rivals’ plantations, during this interlude a whole generation of enslaved Africans still worked in iniquitous captivity throughout the Caribbean. Just as in Jamaica, the punishment meted out to the revolt leaders was swift and brutal. The bodies of executed leaders were put on display to terrorise other enslaved Africans into submission. The revolt lasted for only a few days but had monumental effects in forcing abolition in Britain.

Harding, who began researching the book after discovering that his family had owned businesses that sold tobacco cultivated by enslaved Africans in the Caribbean, intersperses the story of the Demerara uprising with earnest discussions with scholars and activists in Guyana and Britain about what reparation for slavery might look like. This ranges from familial repayment of “white debt” by sponsoring scholarships, to disbursing funds to descendants of the enslaved, as with the University of Glasgow agreeing in 2019 to transfer £20m to the University of West Indies in atonement for its historic ties to the slave trade. Pulling down statues of slaveholders, many of which were erected in the period of anticolonial revolt from the late-19th century onwards, has proven much more contentious. A debt jubilee – writing off the high levels of public debt held by Caribbean states – seems even less likely.

There is no reckoning to be had with the legacy of slavery in a country that denies its own role in it. Britain’s refusal to settle its debts of slavery and colonialism not only wrongs the formerly enslaved and colonised; it also has corrosive effects on the British themselves. Koram begins Uncommon Wealth with a discussion of British denial about the after-effects of empire and colonialism – a tendency the scholar Paul Gilroy has diagnosed as “postcolonial melancholia”, a pathological inability to face colonialism’s malign legacy in British lives. To examine this repressed legacy, Koram invokes the great Martiniquais poet and statesman Aimé Césaire. In his Discourse on Colonialism, written in 1950, , Césaire portrayed Hitler as a kind of boomerang effect of the dehumanising tendencies of colonialism: “colonial activity, colonial enterprise, colonial conquest, which is based on contempt for the native and justified by that contempt, inevitably tends to change him who undertakes it; the coloniser, who in order to ease his conscience gets into the habit of seeing the other man as an animal, accustoms himself to treating him like an animal, and tends objectively to transform himself into an animal.”

Koram tacks back and forth between various moments of decolonisation in Ghana, Singapore and elsewhere, and the wreckage that the rebounding of colonialism has wrought in Britain itself. Each thoughtful chapter tells a story of how the travesties “over there” inevitably end up over here. The symptoms of Britain’s colonial hangover, in Koram’s telling, include the entrenchment of corporate privilege, the intensification of inequality and poverty, the erosion of state welfare provision, the outsourcing of state functions to cronies, and even Britain’s departure from the EU.

The British state’s unbending support of colonial corporations led to the toppling of regimes that dared to nationalise them. Koram compares two such instances that happened more or less contemporaneously: the engineering of a coup in 1953 against Iran’s Mohammad Mosaddegh in support of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (now BP); and the Ashanti Goldfields Corporation, whose British owners supported the 1966 coup against Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana. Koram shows how such unconditional backing of colonial firms enabled them to exploit people and the natural environment with impunity, to employ chicanery to avoid taxes, and to work to erode the state’s regulatory capacity.

In another fascinating chapter, Koram excavates Enoch Powell’s tirade against fixed exchange rates alongside his “Rivers of Blood” speech and shows in fine-grained detail how Powell’s defence of the free market, influenced by the father of neoliberalism Friedrich Hayek, and his anti-immigrant nationalist politics were both reactions to the end of the empire. Restoration of the status quo ante for Powell required hardening borders against the immigrants that decolonisation had created, and shrinking the welfare state that had helped to expand equality among the “lower orders” in Britain itself.

Most relevant to today’s headlines, Koram recounts the history of the creation of a network of offshore tax havens – “Britain’s second empire”, as the journalist Nicholas Shaxson has termed it – in response to decolonisation. During the era of the disintegration of the British empire,British capitalists decamped from the newly independent states and took the material assets and wealth of the former colonies with them, carefully salted away in secretive accounts in islands that remain part of the empire. While the offshore shelters in the Bahamas or Cayman Islands seem far away, the City of London is itself a kind of offshore island, “a financial sun around which a solar system of offshore tax havens orbits”. Britain’s desire to reinstitute direct rule in the Virgin Islands is part of protecting this constellation of overseas financial and corporate infrastructures.

Uncommon Wealth shows how so many of the institutions and practices that have degraded life in Britain – from public austerity and inhumane border regimes to tax evasion and cronyism – emerged from the ruins of a vicious empire. In this sense, not only colonialism itself but the laws and institutions Britain has forged to mitigate the effects of its formal demise on the beneficiaries of empire have rebounded on its ordinary people. In the end it was not liberty that Britain granted the world, but austerity, financialisation, corporate sovereignty and a rule of law that protects the wealthy and the powerful. The infliction of pain on the colonies enriched the colonial officials and capitalists whose degraded, brutal world we all now live in.

Laleh Khalili is a professor of international politics at Queen Mary University of London and author of “Sinews of War and Trade: Shipping and Capitalism in the Arabian Peninsula” (2021)

Tacky’s Revolt: The Story of an Atlantic Slave War

Vincent Brown

Belknap Press, 336pp, £28.95

White Debt: The Demerara Uprising and Britain’s Legacy of Slavery

Thomas Harding

Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 320pp, £20

Uncommon Wealth: Britain and the Aftermath of Empire

Kojo Koram

John Murray, 304pp, £20

Source: New Statesman

Featured image: Enoch Powell’s “Rivers of Blood“ speech of 1968 was a reaction to the end of empire. Photo by Evening Standard/Hulton Archive/Getty Images