In a suburb of Chicago, the world’s first government-funded slavery reparations programme is beginning. Robin Rue Simmons helped make it happen – but her victory has been more than 200 years in the making

By Kris Manjapra, The Guardian —

It began with an email. On an especially cold day in Evanston, Illinois, in February 2019, Robin Rue Simmons, 43 years old and two years into her first term as alderman for the city’s historically Black 5th ward, sent an email whose effects would eventually make US history. The message to the nine-member equity and empowerment commission of the Evanston city council started with a disarmingly matter-of-fact heading: “Because ‘reparations’ makes people uncomfortable.”

She continued:

Hello Equity Commission,

thank you for the work you are doing. You have the most difficult work of all the commissions because the goal seems impossible … I realize that no 1 policy or proclamation can repair the damage done to Black families in this 400th year of African American resilience. I’d like to pursue policy and actions as radical as the radical policies that got us to this point.

Simmons went on to invite the equity commission to join her in exploring “best actions” and pursuing “the light at the end of the tunnel”. The email, five paragraphs and 350 words long, was a spark. By November 2019, Robin Rue Simmons had successfully inaugurated the US’s – and the world’s – first ever government-funded slavery reparations programme.

Evanston is a majority-white university town about 13 miles north of Chicago on the shores of Lake Michigan. From the turn of the 20th century, Black families began arriving in Evanston in large numbers. Around 1915, the process grew into the great migration, one of the greatest internal population movements in modern American history. Over a period of decades, some 6 million Black people left the post-plantation south to fill the growing labour vacuum across the industrial north, and to escape intensifying white supremacist campaigns for retribution and racial rule. These campaigns and policies, collectively called “Jim Crow”, included voter suppression, police brutality and mass incarceration, segregation and the terror of lynching.

Yet the shadow of Jim Crow followed Black families northward, westward and eastward as they migrated. “The negro population of north shore towns [is] steadily increasing, and in Evanston the newcomers are deemed especially objectionable,” reported an article from the Chicago Daily Tribune in 1904. “As a solution of the problem, Evanston citizens are reviving the old scheme of a town for negroes.”

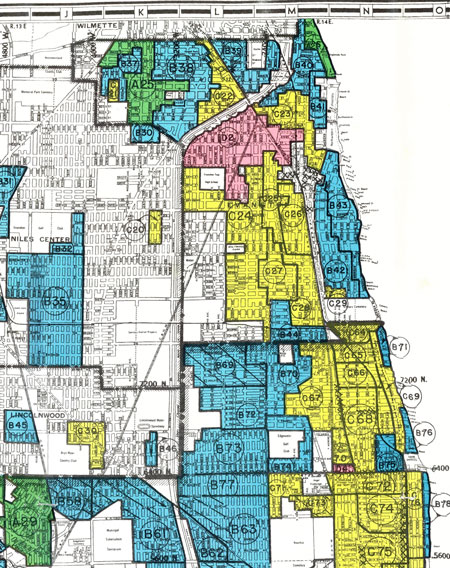

A ‘redlining’ map of Evanston issued in 1940. Photograph: Robert K Nelson/University of Richmond/National Archives

In 1919, with a Black population of 2,500 in a city of 37,000, the Evanston city council created a new triangular zone bounding the Black residential enclave located in the city’s inner core. The zone was tagged for disinvestment: there would be no development of schools, parks, playgrounds, libraries or grocery stores. As documented by the Shorefront Legacy Center, the city’s racial zoning policy was soon complemented by discriminatory realty and housing practices. Starting in the 1920s, real estate agents wrote “restrictive covenants” into house deeds, limiting the resale of properties in “good neighborhoods” to “Caucasians only”. Housing segregation grew more intense during the 30s, when the federal government introduced “redlining maps” for US cities. Neighbourhoods across the nation were graded according to their supposed lending risk for banks. In 1930s Evanston, the 5th ward, home to 95% of the city’s Black population, was graded as “grade D: hazardous; home to an undesirable population”. By the 40s, based on redlining guidelines, banks had largely stopped providing loans to Black families.

And by the 60s, according to estimates by sociologists, Evanston was one of the most segregated cities in the US. In the early 90s, accusations of racist business practices led to two federal lawsuits against Evanston real estate firms. Recent data shows an ongoing story of disinvestment. In 2019, banks offered 1,487 mortgages to homebuyers in Evanston. Only 95 of those went to Black customers. Nationwide, Black families owned fewer homes in 2018 than they did 30 years ago. The wealth gap separating Black families from their white peers has grown exponentially during this same 30-year period.

Having grown up in Evanston’s 5th ward in the 80s, Simmons knows this story personally. When she reached third grade, she transitioned from a Black church school to a regular public school. Since the ward had no public schools, that meant a daily commute. “Evanston is a small city, so [school] wasn’t far, but it wasn’t in my neighbourhood,” she told me recently. “I don’t think the bus came to our neighbourhood.” Instead, her grandfather dropped her off at school every day in his paint contractor’s van – something she loved, especially when she got to sit atop the five-gallon bucket in the back.

Even though her neighbourhood had no public school, no grocery store, few parks and no access to Evanston’s lakefront, Simmons grew to cherish what the Black community had created here, amid this infrastructure of enforced deprivation. As a high school senior and head of the student government, Simmons was already on the speaker’s circuit of local Black churches. “The church is something I was introduced to early on, in order to navigate a system where there are barriers around you no matter how hard you work,” she said.

When Simmons was 19, her family had to sell their home to pay for her grandmother’s cancer treatment. There were no other family assets available. Structural racism and discrimination conspire to drain Black families of wealth, preventing them from creating financial safety nets that can span generations. Black people know what it’s like, generation after generation, to confront the racial wealth gap as they start all over again. After losing her beloved grandmother, Simmons did just that. “My story is not about being downtrodden, but underresourced,” she told me. Simmons began college while working at the mall to make ends meet. By 22, she obtained her real estate licence and started a general contracting business. Eventually, she became a property developer focused on building affordable housing in Evanston, and entered elected office in 2017, aged 41.

Today, the average income of Black families in Evanston is $46,000 less than that of white families; Black people’s life expectancy is 13 years shorter than for white people. And more than 60% of all people arrested in Evanston are Black, even though they represent just 16% of the population. Robin Rue Simmons, like all reparationists before her, believes that “something just as radical” as the harm itself is needed as remedy.

In June 2019, Simmons and the equity commission launched a “solutions only” reparations plan focused on addressing the economic damage done to Black residents by Evanston’s history of redlining, racial zoning and discrimination by banks and real estate firms. Simmons began a series of community consultations with hundreds of Black Evanstonians. The meetings led her to propose $25,000 grants to eligible Black homebuyers in Evanston, along with additional funds to assist Black homeowners in paying property taxes and completing home renovations. The community also asked for the creation of the first-ever public school in ward five.

On 25 November 2019, the Evanston city council passed the US’s first – indeed the world’s first – legislated and funded reparations programme to acknowledge and address the intergenerational disparities of racial slavery. The $10m fund will be resourced by the new municipal income tax on cannabis. There is justice in this, too, since the unequal enforcement and prosecution of marijuana prohibitions has served as a major mechanism by which Black youth are criminalised and shoved into the US’s prison-industrial complex.

Simmons sees the current dispensation as the beginning of something much greater and longer-lasting. “We are focused on breaking the racial wealth divide,” Simmons told me. “My hope is that the fund grows tenfold as other institutions and donors follow our lead.”

It can sometimes seem as though discussions of reparations are idealistic or theoretical debates, or even a relatively new discussion in the aftermath of the world wars. In fact, if we look at the story of actual reparationists – people such as Simmons and her predecessors – we see people have been making these demands for centuries. And during this time huge sums of reparations have already been paid – just the wrong way, to enslavers and their descendants. The long story of reparations is not just about the past, but about how we re-orient ourselves towards past crimes and their ongoing effects shaping our present – and how we break that cycle.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the policy of paying reparations to former slave-owners was standard practice among colonising European and American states. In 1792, at the dawning of the Haitian revolution, when masses of enslaved people rose up against French colonial power, destroying the plantations and constructing their own government, the French state began to pay the exiled former slave owners the secours, or a state-funded compensation for their property losses. This assistance was offered not only to former enslavers, but also to their descendants. It was paid by successive French governments for more than 100 years, ending in 1911, as historian Mary Lewis has detailed.

This government support was not deemed sufficient by the former enslavers, who also demanded what they explicitly called “réparations” from the Haitian people themselves. In 1825, France stationed 14 warships off the Haitian coast and threatened the destruction of the nation’s main port cities unless a huge sum of reparations – the indemnité – was paid. The Haitian government was forced to pay perverse reparations for its own revolution: ultimately 90m gold francs, plus an additional 135m gold francs in bank interest and fees to France, over the course of more than 120 years, concluding only in 1947.

The British empire offered the largest reparations bounty of all to its former slave owners: a total of £20m in 1833, which represented 40% of the national budget, along with the statutory re-enslavement, or “apprenticeship”, of emancipated people for a subsequent four years. More than 44,000 enslavers living in the Caribbean and in Britain benefited from this feeding frenzy. Some of the reparations payments were paid in cash, but a segment was rendered in financial assets that paid dividends for decades afterward. The reparations payments were so large that the British state opted to take out a loan from the Rothschild banking syndicate to raise the funds. Over the past nine months, I have contacted the Rothschild Bank six times for comment about this loan. Initially, they acknowledged receipt of my queries and promised a response. Since July, all my follow-up inquiries have been met with silence. What is clear is that British taxpayers paid back the financiers of slave-owner reparations for 180 years, a public obligation that ended only in 2015.

The Afrikan Emancipation Day Reparations march in London, earlier this year. Photograph: Jonathan Brady/PA

Britain’s model of using state funds and massive government loans to compensate former slave-owners for their “losses” served as the template for other European powers. The Danish and the Swedish paid reparations to enslavers through their own “compensated emancipations”. The Dutch state paid £1m to its 5,316 enslavers in 1863, and guaranteed the continuation of African bondage in Suriname for a subsequent 10 years after emancipation. In Spanish Puerto Rico, enslavers were showered with reparatory parting gifts: money, bonded Black labour and land grants.

In the US, reparations to enslavers have been consistent state policy since the first emancipations of the 1770s in the revolutionary American north. Enslavers in states such as Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York and New Jersey were granted reparations packages in the form of rights to the ongoing involuntary labour of enslaved Black children for up to 28 years, as well as guaranteed pensions. In Connecticut, for instance, a minister named Reverend Thompson had title to an enslaved boy named James Mars, born in 1790 in Connecticut, after the state abolished slavery. The law allowed Thompson to keep Mars enslaved until age 25, and even to send the boy down to Virginia where Thompson owned land and could enslave Mars for life. Mars only escaped this fate thanks to the ingenuity of his parents, who “stole” their own son and fled elsewhere in New England in order to remain together.

Reparations for enslavers worked not only through law but also through custom. Long before segregationist Jim Crow laws codified the section of the bus (at the back) where Black people had to sit, or the (underresourced) schools and hospitals that Black folk could attend and use, the everyday codes of white supremacy kept freed Black people in the condition of an undercaste in the US north as well as across the south, as the writer Isabel Wilkerson has shown.

Meanwhile, post-slavery laws were often used to reconstitute slavery by another name. New Jersey passed its “act to abolish slavery” in 1846. And yet white households were allowed to keep formerly enslaved people as “apprentices for life”. Unlike the enslaved, apprentices had the right to sue for their freedom if they were treated abusively – but this right remained largely elusive. It was not until 1865 that the last New Jersey “apprentices” were freed. Even then, this new general emancipation contained various loopholes for the continuation of slavery. For example, the 13th Amendment to the constitution prescribed “involuntary servitude” as punishment for crime. The resulting racial regime of “convict leasing” almost exclusively targeted Black men and women, incarcerating them in vast numbers and forcing them to perform inhumane and often deadly unpaid labour.

***

From the moment slavery was abolished, emancipated Black people demanded redress. In 1777, at the time of the first emancipations in the revolutionary American north, a group of emancipated African people wrote to the Massachusetts legislature. Many of the petitioners had been kidnapped from homes in Africa, “unjustly dragged, by the cruel hand of Power, from their dearest friends, and some of them even torn from the embraces of their tender Parents”.

The petitioners did not plead for the barest form of freedom. They asked to be “restored to the enjoyment of that freedom which is the natural right of all Men and their Children”. They wanted “every social privilege … requisite to render Life even tolerable”. The Massachusetts legislature never responded to the principles laid out by these Black reparationists. Silence itself has long been a weapon used by those in power.

In response, Black folk took up reparations for slavery as an enduring social movement, bequeathed from generation to generation. Like traits passed down through a large, scattered family, the reparationist movements of the 19th and 20th centuries exhibited variations on certain themes. Ideas of repair focused on the need to restore both personal and collective privileges and benefits.

The same Barbados-born Black lawyer of Boston, Prince Hall, who wrote the 1777 petition to the Massachusetts legislature, wrote once again to the same body in 1783, demanding personal reparations in the form of an annual pension for Belinda Sutton, a Black woman who had been enslaved in Medford, Massachusetts, for five decades. Although Sutton’s request was granted, she received only a single payment. Hall wrote a third reparations petition in 1787, this time on behalf of a group of freed Black people asking to be repatriated to Africa. In the coming century, reparationists often imagined a reverse exodus, out of the land of exile and enslavement, and home to Africa. The “back to Africa” movements led by the likes of Paul Cuffe, Martin Delany, Chief Alfred Sam and Marcus Garvey were all Pan-Africanist in spirit. For these leaders, reparations was about reconstructing the meaning of home, and Africa best represented that profound wish.

Across the Caribbean and the American south, Black reparationists also sought new relationships with land in order to repair the damage caused by generations of brutal plantation labour. In 1861, formerly enslaved Jamaican peasants sent a petition to Queen Victoria demanding land for collective cultivation. The request was ignored. On 12 January 1865, near the end of the American civil war, Black leaders in Savannah, Georgia met with Maj-Gen William T Sherman of the victorious anti-slavery Union army. When Sherman asked the group what they wanted after emancipation, they made a reparationist argument. Since “slavery is receiving by irresistible power the work of another man, and not by consent”, they argued that the remedy should be “to have land, and turn it and till it by our own labour … [so] we can soon maintain ourselves and have something to spare.”

Sherman’s field order No 15, issued three days later, redistributed 400,000 acres of coastal land, stretching from Charleston, South Carolina to the St John’s River in Florida, to Black families in 40-acre plots. However, soon after assuming office in May 1865, President Andrew Johnson, himself a former slave owner, gave instructions to cease all land reparations to freed people by the summer. He ordered all plantation lands returned to the former enslavers. In response, Black reparationists set up mutual aid societies, Black churches, community schools and grassroots savings banks for their people.

If reparationists across the US had previously been working in small local groups, largely unknown to each other, that began to change by the turn of the 20th century. Popular reparationist movements came into their own, using new technologies of communication and travel to reach mass audiences. In 1898, Callie House, a Black seamstress from Nashville, Tennessee, and child of the “Freedom generation”, established the Ex-Slave Mutual Relief, Bounty and Pension Association and began collecting membership by mail from Black folk across the South. She gathered more than 600,000 signatures on a petition to the federal government for reparations legislation. The petition asked for maximum benefits to go to formerly enslaved people over 70 ($500 upfront and $15 per month in pension), as compensation for the “debt owed” to them for their life of unpaid, enslaved labour. House’s organisation also coordinated mutual aid for all its members, including covering burial costs and providing financial assistance in times of sickness and distress. The organisation demanded, but also performed, reparations.

Audley ‘Queen Mother’ Moore in April 1996, pictured with Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, right, and the activist Kwame Toure, centre. Photograph: Kathy Willens/AP

The scale of reparationist organisation took another leap in the 1950s through the work of Audley Moore, known as the Queen Mother of reparations movements. Born in 1898 to sharecroppers in Louisiana, Moore grew up in New York during the Harlem Renaissance, absorbing waves of Black internationalism and anti-colonial thought. Under Moore’s direction, reparations took on a globalist dimension. At the age of 80, Moore reflected on the importance of reconstructing home in the aftermath of slavery: “I knew that there was no land in the world called Negro land, and that in analysing all of the histories of the other peoples, they all came from land. And those who didn’t come from land, who robbed land, as soon as they robbed land, they changed the name of the land, and then they named themselves after the new changed name of the land.” She continued: “We’re Africans, no matter where we born … Just remember, you’re African wherever you are”. Moore’s emphasis on what historian Robin DG Kelley calls “the inner life” and “imagination” of people in the Black diaspora, and on the need to transform the values of society as a whole, inspired a new generation of Black Power organisers in the 60s and 70s.

Moore submitted a petition with more than 1 million signatures to President Kennedy in 1963, the centennial year of the Emancipation Proclamation. The petition demanded that the US government pay no less than $500tr over the course of four generations, as a partial payment of what was owed to African Americans. The money was to be controlled by the Black community, not by a small elite, and was to “benefit the whole people” through the construction of infrastructure, industry, educational institutions and health services. Just as Robin Rue Simmons would do a half-century later, Moore insisted on pursuing policies and actions as radical as the radical policies that got us to this point.

Moore’s epic reparations demand made it as far as President Kennedy’s secretary, and then stopped. Silence is power.

The struggle for reparations is a global story, not just an American one. For example, four high-profile international conferences of Pan-African reparationists took place in the UK between 1900 and 1945. But perhaps the leading 20th-century British voice on reparations was Bernie Grant, a firebrand member of the Labour party. Grant was born in Guyana in 1944. His natal country, still a colony of Great Britain at the time, was one of the most exploitative and notorious British plantation zones. British Guiana – as Guyana was known before it gained independence in 1966 – was a great sucrose mine, as investors and planters squeezed more sugar profit out of Guyana by the late 19th century than from anywhere else in the empire except for Mauritius.

Arriving in London with his parents in 1963, Grant quickly made his way into trade union politics. He was a larger-than-life figure who loved reggae as much as Irish folk music. In 1987, as a leading member of the Labour party’s Black Sections, Grant became one of the first four Black Britons to enter parliament, representing the London constituency of Tottenham. He was known before his parliamentary career, and even more so during it, as the most outspoken and fearless spokesperson for the Black experience in Britain. Among the 650 MPs at the state opening of parliament after he was first elected, Grant was the Black man dressed in African robes.

Grant’s constituency office at 3 Devonshire Chambers, Tottenham High Road, located above a pharmacy, became the country’s epicentre for Black political organising. In 1993, he worked with a Nigerian reparations leader, Chief MKO Abiola, and the Organization of African Unity, to hold a Pan-African conference on reparations in Abuja, Nigeria. Attendees published a proclamation stating: “The damage sustained by the African peoples is not a ‘thing of the past’, but is painfully manifest in the damaged lives of contemporary Africans from Harlem to Harare, in the damaged economies of the Black world from Guinea to Guyana, from Somalia to Suriname.” The statement concluded with the demand that the international community “recognize that there is a unique and unprecedented moral debt owed to the African peoples which has yet to be paid”.

Grant’s participation in the Abuja conference in 1993, and the African Reparations Movement he established with colleagues upon returning to London, stoked the fire of reparationist breakthroughs in coming decades. These “firsts” actually began in the lead-up to Abuja, when, in Birmingham, he gave his famous “Reparations or Bust!” speech, making clear to his audience why the struggle to abolish the “third-world debt” of Africa and the Caribbean was part of a shared programme to also confront “racial attacks and racial harassment” in the UK and across Europe.

After returning from Abuja, on 10 May 1993, Grant brought a motion before parliament to ratify the Abuja Proclamation. It was the first time that reparations had been discussed as part of the British parliament’s official business. Three years later, Grant’s collaborator, the human rights lawyer Anthony Gifford QC, would raise the question of reparations for the first and, so far, the only time in the House of Lords.

The documents in the Bernie Grant archive in London provide ample evidence of the vibrancy and breadth of the African Reparations Movement. Members of the movement began research projects to unearth the role of British banks in slavery; demonstrated in front of museums to demand the restitution of African museum artefacts, such as the Benin Bronzes; established a memorial site on the Devon coast where the remains of enslaved Africans from St Lucia, dating from 1796, were thought to have been identified; demanded official acknowledgment and apology by the British government for slavery’s crimes against humanity; and developed plans to advocate within international bodies, including the United Nations and the international court of justice, for African reparations. Graham Gibson, who was a university student at the time and travelled with Bernie Grant to Abuja, told me he recalls the feeling of that 1993 moment: “You started to feel like things can change. I felt strong. That’s the only way I can describe it. As a Black person, I felt I was not afraid.”

Since Grant’s death in 2000, reparationist leaders, such as Esther Stanford-Xosei and Kofi Mawuli Klu of Parcoe (Pan-African Reparations Coalition in Europe), have ensured the generational continuity of the movement. Stanford-Xosei and Klu successfully lobbied Labour representatives to raise the matter of reparations in parliament in 2004. In the years since then, the situation for Black people in the UK has grown worse. In the past decade, as Stanford-Xosei points out, cuts by the government have damaged Black British cultural institutions, and the Black “voluntary sector”, including supplementary schools, community centres and civic organisations. Black homeownership per capita in the UK is lower today than it was in the 80s. Incarceration rates of Black people in the UK have increased drastically. Black Britons have the highest unemployment rate of all groups. Black Britons are four times more likely to die of Covid-19 than white Britons. And when it comes to the way knowledge is produced and disseminated in the UK, the situation is also dire. Only 1% of professors in the UK are Black, and only 1.2% of PhD students.

In the face of this aggravated disinvestment, the social movement for reparations has not abated. Building on the work of Parcoe’s Stop the Maangamizi Campaign, on 15 July 2020, Lambeth council in London, led by Green party representative Scott Ainslie, became the first local authority to pass a successful motion calling for a parliamentary reparations commission to address the impact of slavery on current racial inequalities in the UK. Meanwhile, grassroots activists continue their work, organising events such as the Afrikan Emancipation Day Reparations march, which is held each year on 1 August. Hundreds turned out for the march in Brixton this year.

A childhood photograph of Robin Rue Simmons shows her as a three-year-old girl with a proud afro, a child clearly beloved by the world around her. “I grew up in a community that celebrated me and wrapped their arms around me,” she told me. In the photo, she is standing in front of her two-storey childhood home at 1827 Ashland Street, the house her family would lose by the time Simmons left high school.

Four decades after that photo was taken, on 11 December 2019, Robin Rue Simmons spoke about the path to the US’s first government-funded slavery reparations programme at a packed celebration at the First Church of God in Evanston. The church is located a 10-minute walk from the house where she grew up. A video of the event shows Simmons’ calm audacity: “We needed to move our efforts beyond apology and ceremony,” she told her audience of more than 600 people that night. “A reparative policy was the next option, and really the only option.”

In this statement of radical certainty, Simmons drew on the fire of Queen Mother Audley Moore’s unanswered demands to the president of the United States back in 1963. She drew on the acumen of her senior advisers from the National African American Reparations Commission (NAARC): Dr Ron Daniels, Lionel Jean-Baptiste, Iva Carruthers, Nkechi Taifa, as well as Kamm Howard of N’Cobra. Together, they embodied more than a century of experience in the struggle.

Simmons’ work also builds on the earlier achievement of Evanston alderman and now circuit court judge, Lionel Jean-Baptiste, who, in 2002, passed a city council resolution demanding reparations after the United Nations’ Durban conference declared slavery a “crime against humanity”. The fire for reparations also needed the kindling of community-based educators, such as Dino Robinson, who, in 1995, established the Shorefront Legacy Center to retrieve, archive and redeem the Black history of the city. Evanston’s success also relied on the active commitment of white allies, such as Nina Kavin and her Dear Evanston project, who sees her work as supporting Simmons by working with white communities in Evanston so that they don’t opt to “unsee the racial divide”.

Beyond the local level, Simmons historic success draws on the same fire burning in Caribbean. A collection of inspiring quotations written on sticky notes peppers a wall in her office. One is a quote from the Barbadian historian and reparationist Sir Hilary Beckles: “Slavery is over, but we are in the jetstream of the consequences.” Beckles, who is also the vice-chancellor of the University of the West Indies, recently led the Caribbean Community of Nations in calling for a reparations summit with the governments of the UK and Europe. “We have argued in the Caribbean that reparatory justice is about development, and that Britain and Europe do indeed own a debt to this region, a debt that is recognized, a debt that can be computed, a debt that is historically sound, in terms of its legitimacy.”

Simmons’ strategy of insisting on a “solutions-only” bill reflects important changes taking place in the way reparations is now being pursued in the US Congress. Introduced in 1989 by the late congressman John Conyers, house resolution 40 asked for a federal committee to study the legitimacy of African American claims for reparations. However, in 2017, during Rep Conyer’s last year in Congress, it was transformed from a “study bill” into a “remedy bill”. It now calls for a federal committee to study different reparations plans for implementation.

Now sponsored by congresswoman Sheila Jackson Lee, HR40, like Simmons’ Evanston resolution, is a “solutions only” bill, and it now has more support than ever before. In 2000, it had only 16 co-sponsors; today, it has more than 150 in Congress. This kind of support suggests that the time may be nearing when HR40 will move out of the judiciary committee and be put before the US Congress. In a sign of the growing momentum behind this issue, on 1 October, the state of California established its own commission to study and develop proposals for reparations for slavery.

But, as lifelong reparationist Ron Daniels notes: “When HR40 passes, that’s the beginning of the struggle, not the end of it.” For reparationists, history, in the long wake of slavery’s devastations, is always an experience of beginning, again.

Source: The Guardian