How disinformation campaigns suppress the Black vote

During the Democratic debates on June 27, Senator Kamala Harris had a standout moment. Former vice president Joe Biden, the front-runner, had recently made news for defending his work in the seventies with senators who advocated racial segregation, telling donors that, in those days, “At least there was some civility. We got things done.” Harris, the only Black woman in the field, seized an opportunity to call out Biden’s imperfect record on race, and focused on his history of opposition to busing that would integrate schools.

“There was a little girl in California,” Harris said—her eyes closing for a moment—“who was part of the second class to integrate her public schools, and she was bused to school every day, and that little girl was me.” Facing Biden directly, she went on: “So I will tell you that on this subject, it cannot be an intellectual debate among Democrats. We have to take it seriously; we have to act swiftly.”

Many people watching, Harris supporters or not, were moved by the sincerity of her message. Of course, the internet provided dissent. That evening, Ali Alexander, a right-wing provocateur, tweeted, “Kamala Harris is *not* an American Black. She is half Indian and half Jamaican. I’m so sick of people robbing American Blacks (like myself) of our history. It’s disgusting.” Immediately, Alexander became part of a smear campaign. His tweet was reposted thousands of times and shared by Donald Trump Jr. to some 3.65 million followers with the line “Is this true? Wow.” (Trump later deleted the post.) It’s true that Harris is of Jamaican and Indian descent; she is also Black and a native citizen from Oakland, California.

The incident was referred to by several news outlets as “Birtherism 2.0,” a nod to the conspiracy theory that emerged during Barack Obama’s 2008 campaign and launched Donald Trump’s modern political ambitions. Back then, the claim—that Obama was born outside the United States and therefore constitutionally ineligible to become president—was viewed as an old-fashioned lie, propagated by a reality television star with a loyal following. Today, the spread of such messages is interpreted differently, thanks to the Senate Intelligence Committee and Special Counsel Robert Mueller, who determined that Russians sought to influence America’s 2016 elections via social media channels, in many cases targeting the Black community. And, after months of speculation, it became clear that Russian activity continued even after Trump entered the White House.

Though the Harris campaign has been unable to prove that Russian bots were behind the tweet’s virality, the episode bore the signs: Caroline Orr, a reporter focused on disinformation, observed that a group of accounts all picked up Alexander’s tweet within minutes, “astroturfing” it—that is, planting the message but masking its origin, to make something artificial appear real—within the #Blexit movement (a play on Brexit for a Black constituency). As in the 2016 election, which revealed how vulnerable the American electorate is to outside influence, the Harris claim used the fault line of race, a potent motivator, to foment division, create distrust in the democratic process, and turn African Americans into disaffected voters.

Propaganda aimed at suppressing the Black vote is not new, of course, but social media has transformed its nature and scale, enabling what New Knowledge, a tech firm, has called “an expansive cross-platform media mirage targeting the Black community, which shared and cross-promoted authentic Black media to create an immersive influence ecosystem.” In newsrooms across the country, as journalists have been grappling with questions of when and how to report on disinformation, they have also faced a logistical challenge. “Unless you’re on Black Twitter, you don’t hear the conversations,” Shireen Mitchell, the founder of Stop Online Violence Against Women, an organization focused on how suppression of the Black female vote is playing out on the internet, tells me. Nuance can be missed, context lost. “If you don’t have a group of people connected to these communities, you’re never going to see it.”

A lot of damage has already been done as reporters have tried to figure it all out. The Internet Research Agency, Russia’s fire hose of election interference, has reached more than 120 million people on Facebook and at least 20 million on Instagram. It also produced 1.4 million election-related tweets and uploaded more than a thousand videos to YouTube. Using sophisticated tactics—from newsbots posting articles to retweets and hashtags on Twitter to cultural media pages built to foster relationships with real people on Facebook and Instagram—the IRA has had an especially dire impact on millions of Black voters, a demographic that disproportionately uses social networks and has a long history of mistrusting the US government.

In a December 2018 report commissioned by the Senate, New Knowledge found that, during the past presidential election, the IRA identified as “assets” people whose trust in Black media could be exploited to share manufactured disinformation on their own accounts. To target them, the IRA put out messages on topics including Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, Black History Month, Pan-Africanism, Black Is Beautiful, and Black Power; some posts also featured seemingly nonpolitical images or memes. The most popular post in the data set analyzed by New Knowledge was an Instagram advertisement for a Black-owned leather goods company called Kahmune; through a phony account, @blackstagram__ (303,663 followers), IRA operatives promoted the ad in order to engage with an unsuspecting user base.

There were other forms of targeting, too: some geographic and newsy in nature, zeroing in on communities for local events and rallies, with race- and police-brutality-related content timed to follow officer-involved shootings; others took up historical conspiracies intended to divide Black people while reinforcing cultural identity. “Once they had enough people and enough of a campaign going and gained their trust, they sent out voter suppression stuff and people believed it,” Mitchell tells me. “We come from a community of mistrust, but when we build trust, it’s hard for us to shake. People didn’t understand what they were looking at.”

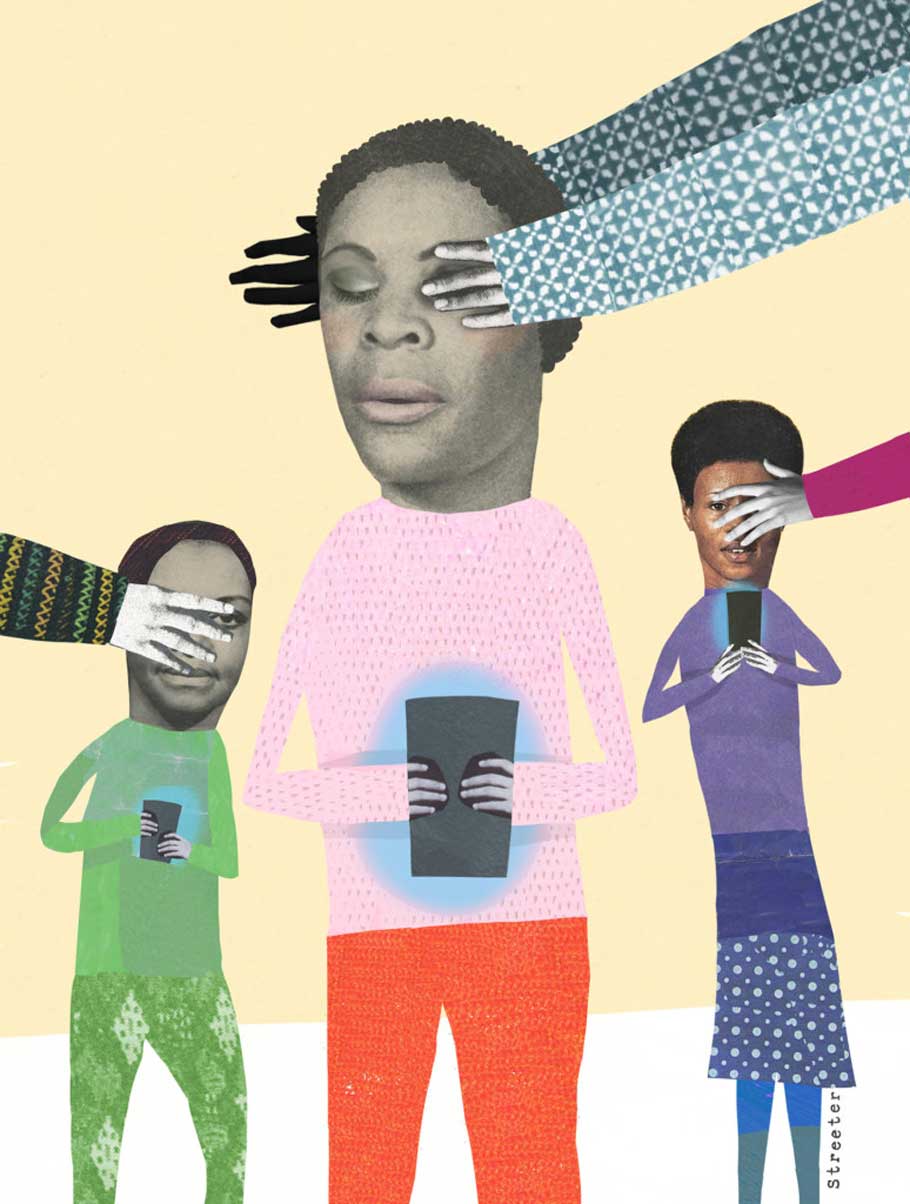

Illustration by Katherine Streeter

The IRA continued to meddle in American politics during the midterms. A year ago, the Department of Justice announced that federal officials had charged Elena Alekseevna Khusyaynova, a Russian national, for her alleged role as the chief accountant for “Project Lakhta,” a conspiracy that would, among other things, “aggravate the conflict between minorities and the rest of the population.” In Florida, the conspiracy deployed @KaniJJackson, an account created around September 5, 2017, that amassed over thirty-three thousand followers. The focus on Florida was clever: Andrew Gillum, the mayor of Tallahassee, was in a neck-and-neck contest for governor against Ron DeSantis, a former congressman.

Gillum, a Democrat, is Black and supported criminal-justice reform; DeSantis, a Republican, is white and backed Trump. The @KaniJJackson account posted on subjects such as gun rights, net neutrality, negotiations with North Korea, Trump, and the midterms themselves, aiming to discourage liberal voters from showing up to the polls. To cover its tracks, @KaniJJackson referred to past Russian interference with American democracy, tweeting on February 7, 2018, “Jeanette Manfra, the head of cybersecurity at the DHS: the Russians successfully penetrated the voter registration rolls of several U.S. states prior to the 2016 election.”

On the ground, the coordinated efforts of Russian agents seemed to work in concert with American operatives intent on using similar tactics to weaponize digital media. For instance, when Gillum backed a ballot initiative that would restore voting rights to former felons who had served out their sentences, his political opponents flooded social networks with ads and stories about him being “soft on crime”; right-wing sites—such as the Daily Wire, the Daily Caller, The Signal, and Breitbart—spread the same message under the guise of news reporting. Those articles would be shared on Facebook, on Twitter, and directly with voters. “It’s illegal to send robotic text messages,”

Joshua Karp, Gillum’s former deputy campaign manager, tells me. “So Republicans figured out a loophole to outsource the sending of text messages to Latin America, where they could cheaply send hundreds of thousands—if not millions—of individual text messages to voters containing negative headlines and facts about Andrew Gillum.” In other words, while the IRA was behind a campaign generating posts en masse that encouraged Black voters to stay home on Election Day, Republicans were fueling a disinformation campaign to motivate conservatives. (A spokesperson for DeSantis didn’t respond to requests for comment.)

More of the same took place during the gubernatorial race in Georgia, where Stacey Abrams, a Black female Democrat, was running in a tight, closely watched election against Brian Kemp, a white male Republican. On November 3, the New Black Panther Party—founded in 1989, condemned by the original Black Panthers, and described by the Southern Poverty Law Center as an “anti-white and anti-Semitic” group—posted photos of NBPP members marching in support of Abrams while carrying rifles. A few hours later, the images were shared on right-wing Facebook groups, including one dedicated to supporting Kemp.

The next morning, Kemp shared one of the photos posted by the NBPP on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter. Soon, the story was picked up by the Daily Caller, Breitbart, and other sites; Fox discussed it on the November 5 episode of America’s Newsroom. “You just had Black Panthers in Atlanta, for example, carrying what looked like semiautomatic weapons, for Stacey Abrams,” Newt Gingrich told viewers. “You want a really radical America? You can get one, and she’d be—if she wins—she’ll be the most radical governor in the country.”

Abrams, for her part, had never associated with the New Black Panther Party, but by the time conservative media had the images, that didn’t matter. On Big League Politics, Laura Loomer stated that “armed Black Panthers” were “campaigning with Stacey Abrams” and that she was committing “an act of racially motivated anti-white voter intimidation.” The accusations piled atop other misinformation attacks that fall—accusing Abrams of being aligned with Communists and the Muslim Brotherhood.

While the IRA was generating posts en masse that encouraged Black voters to stay home, Republicans were fueling a disinformation campaign to motivate conservatives.

Both Gillum and Abrams lost their elections. (Florida’s Voting Rights Restoration for Felons Initiative was approved by a large margin, and in January at least 1.4 million people became eligible to vote, but the state’s Republican leaders later instituted a poll tax that would severely limit its effects.) At the end of last year, the NAACP called for a one-week boycott of Facebook and Instagram, explaining in a statement that the action was meant to protest “the utilization of Facebook for propaganda promoting disingenuous portrayals of the African American community.”

This past Black History Month, Abrams appeared at an event at the Brookings Institution in Washington, DC. Mitchell, of Stop Online Violence Against Women, was there, and asked about the problem of disinformation during the campaign in Georgia. “Disinformation—I will say this, they lied about me on television,” Abrams replied. “It was less about going online to do it. But I do think disinformation campaigns do suppress the votes in a lot of communities, less by giving disinformation about the candidate and more about giving bad information about how elections work.” Voter suppression, she emphasized, was the fundamental harm—the way “fake news” campaigns overwhelm people with a despair and mistrust that turns them away from politics. “If you’re angry, you do something,” Abrams said. “If you’re despondent, you curl up in bed. And so we need people to be angry about voter suppression and out there acting.”

For journalism to adequately cover how disinformation is used against the Black electorate, a solution is having Black journalists on the story. Some, like Rachelle Hampton, a writer for Slate, have been at it for a while. Three years ago, she noticed that Black female activists were unmasking disinformation campaigns targeting Black women online. Though Hampton had never written about disinformation, the subject intrigued her. “I am a Black woman, and the women I was talking to were Black women,” Hampton recalls. “I’ve kind of grown up on the internet, and there are certain ways in which this isn’t a straight-up tech story, so I didn’t have to know a lot about Twitter.” Approaching her sources presented a challenge: many of them had been frequent targets of online harassment, so their guard was up and their accounts were locked down.

When she introduced herself, however, they found her relatable. Her resulting piece described Black Twitter’s relationship to disinformation in a way never seen before; she also highlighted the disappointing response of Twitter executives. Still, Hampton had trouble explaining her findings to her editors, many of whom were older, white, and unfamiliar with the mores of Black women’s activity on social media. “The nuances of what’s happening on the internet where people of color are congregating—they don’t understand the conversation,” Hampton says.

When the Harris “Birtherism 2.0” claims came up, news outlets found themselves tested. To be sure, the story was a plot point in the Democratic primaries, where, given the twenty-four-hour news cycle, virtually anything was fair game; it speaks to the importance of race in the 2020 election and the role of social media, whether at the command of Russian troll farms or partisan instigators. Yet airing the notion that Harris is “not an American Black” plays into a false narrative designed to serve an antidemocratic agenda by sowing division in the Black community. In a case such as this, editors are liable to be misled—and used—by trolls. As Jessie Daniels, a sociologist at the City University of New York whose work focuses on the intersection of race and technology, tells me, “Our institutions, which are often rooted in these legacy, analog systems, are sitting ducks for this digital warfare.”

In the days following the debate, numerous outlets—including the New York Times, BuzzFeed, and NBC—covered the divisive Alexander tweet. Some stories focused on reactions to it; others highlighted the appearance of related articles on the Daily Stormer, a neo-Nazi site, and patriots4truth.org, part of a network of sites that spread fringe conspiracy theories. My newsroom, the Associated Press, published a couple of pieces that corrected false statements about Harris. “We check claims from any newsmaker in the world of politics,” Karen Mahabir, head of fact-checking at the AP, tells me. It seemed like a case in which journalists were getting better at identifying disinformation for what it was, and appreciating the complex web in which it operated.

Yet there are limits to what journalists know and can discern in real time—especially if they’re not deeply versed in the particulars of an online community such as Black Twitter. “For better or for worse, journalists get a lot of their stories off of Twitter,” Hampton says. Reporters need to be sophisticated in their skepticism, she explains, and appreciate that there is often more to messages than what appears on the surface. “If you are treating Twitter like a distillation of American politics, not being able to parse what’s real from what’s fake is going to distort what you’re actually thinking.”

This article was originally published by Columbia Journalism Review.

Featured image: Illustration by Katherine Streeter