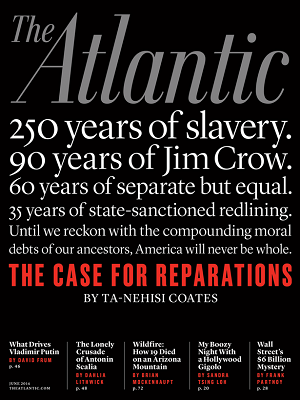

At the Sixth and I synagogue in Washington on Thursday night, people were reselling tickets out on the street as if a playoff game was taking place inside, rather than a talk by Ta-Nehisi Coates, a national correspondent for the Atlantic. The subject of the event was Coates’s recent cover story for the magazine, “The Case for Reparations,” which has broken traffic records and vanished from newsstands.

(The Atlantic)

While the piece is popular, the turnout for Coates and the reception he received in the sanctuary reflected something larger than the enthusiasm for a single article. “The Case for Reparations” managed to revive and reframe a major policy debate about race in the United States. But the piece is part of a larger project, a redefinition of what counts as a legitimate conversation about race in the United States and an attempt to define what intellectual credentials are required to enter that debate.

At Sixth and I, Coates recalled what the standards were when he was in college.

“Being a student at Howard University and reading the New Republic … picking up this magazine which does what you hope to one day do, opinionated, long-form articles with reporting, and watching them talk about black people, and having no black people on staff, having no black people in the room … Do you think they’re genetically stupid?” he mused, remembering a fabricated piece that magazine published that suggested African Americans were uninterested in blue-collar jobs like driving taxis and its role in advancing Charles Murray’s work on race and intelligence.

Coates has had a long career in journalism, but he made his debut in the Atlantic in 2008 with a feature on Bill Cosby’s gospel of black male responsibility that is really a long meditation on the persistence, and persistent inefficacy, of respectability politics — the idea that a minority group can evade structural disadvantages and ingrained prejudice through self-improvement.

“Racism is a kind of fatalism, so seductive, that it enthralls even its victims,” he wrote this January after the Seattle Seahawks’ Richard Sherman, a Stanford graduate, was labeled as a thug after giving a fired-up sideline interview. “But we will not get out of this by being on our best behavior—sometimes it has taken our worse. There’s never been a single thing wrong with black people that the total destruction of white supremacy would not fix.”

The campaign to eradicate respectability politics is not yet complete. The first question put to Coates at Sixth and I was why he had not written about fatherlessness in “The Case for Reparations.” But when the Atlantic’s Jeffrey Goldberg, who was moderating the panel, posed the question of black culture, Coates’s response laid out the case for a major shift in focus.

“It was policy that got us redlining,” Coates argued. “It was policy got us housing segregation. There’s policy behind all of it. The slave trade was policy. When that becomes a substitute for something, I don’t know, I have a problem with it.”

“The other thing is,” he continued, “we have tons of academic research on the impact of redlining, on the impact of not being able to get the G.I. Bill, on the impact of lynching, on the impact of terrorism. We have tons of research on what that did and what that does to community. Culture not so much. Not so much. It’s a little harder to quantify. So why do we spend so much time talking about the thing that we have the hardest time quantifying, and so little time talking about the thing that we know?”

In a debate with New York Magazine’s Jonathan Chait and in discussing “The Case For Reparations,” Coates has repeatedly discussed his own education in this history of policy, with bows to historians Nell Irvin Painter and Isabel Wilkerson. And he emphasizes the need for anyone who wants to engage seriously on these issues to do the same.

“The most common response I get from white people is ‘I had no idea. I had no idea. I had no idea.’ I think that’s a sincere reaction,” Coates told Goldberg. What he did not need to say is that such sincerity is a starting point from which his interlocutors can begin to remedy their ignorance.

If pushing respectability politics to the margins, and perhaps even beyond them, of the political conversation was the first salvo in Coates’s project, “The Case for Reparations” is an attempt to enlarge the territory of debate. One of the significant critiques of the piece has been the question of feasibility.

Coates’s initial proposal, in keeping with his focus on study and debate, is an oft-introduced bill that would require a study of reparations, but that has shown little chance of advancing in Congress. On Thursday, Goldberg raised the possibility that President Obama might take up the cause, a prospect Coates suggested would be wildly divisive in advance of any major shift in the American polity.

As Andrew Beaujon notes at Poynter, Coates was very clear that he has no intention of quitting journalism for activism or politics. But in a sense, the role he outlined for himself is even more ambitious: “I think there has to be some respect for a journalist’s or a writer’s role in a democracy,” Coates told Goldberg. Writers may not be the people organizing bus boycotts or mobilizing for women’s suffrage, but they do help define what is “too radical” and what is not.

Heated discussions about what counts as acceptable sentiment are critical to many of our present political debates. From the discussion of sexual assault playing out in the pages of this newspaper to the fight for the rights of transgender people, the stakes are not just policy, but the boundaries of legitimate conversations. As much as we might wish it to be true, the American public has reached no agreement on what counts as outlandishly cruel and what is productive in many areas of public life.

The extent to which Coates has been able to re-position the goalposts in his own area of focus and repaint lines on the field to set new markers of progress toward racial equality is rather remarkable. Those victories may be hard to preserve, and they may be even more difficult to replicate. They may not even translate into policy. But as Coates put it last night, “Somebody’s got to work on the edge of imagination.”