By Roy E. Finkenbine —

In an interview conducted in 2002, the late Helen Hornbeck Tanner, an influential historian of the Native American experience in the Midwest best known for her magisterial Atlas of Great Lakes Indian History (1987), reflected on the considerable record of “coexistence and cooperation” between African Americans and Indians in the region. According to Tanner, “[an] important example of African and Indian cooperation was the Indian-operated Underground Railroad. Nothing about this activity appears in the historical literature.”

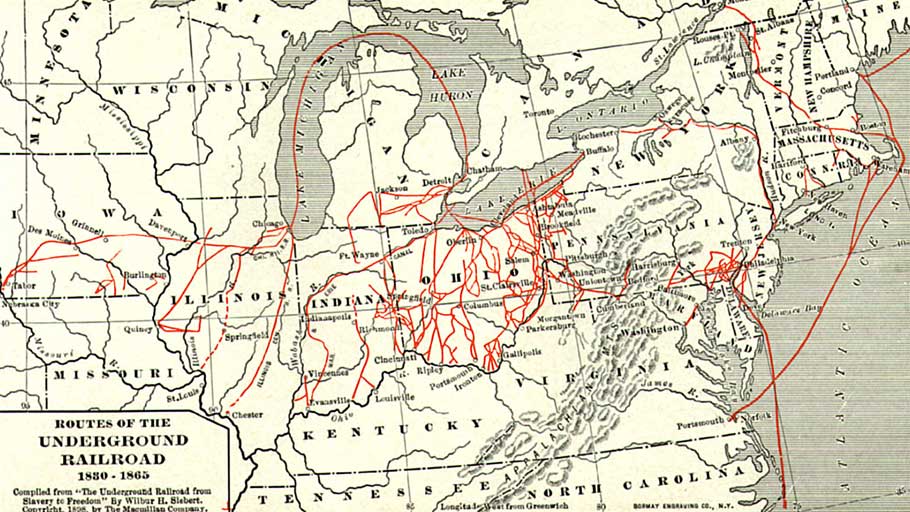

Tanner’s assertion is largely true. Native American assistance to freedom seekers crossing through the Midwest, then often called the Old Northwest, or seeking sanctuary in Indian villages in the region, has largely been erased from Underground Railroad studies. Two key examples from the historiography of the Underground Railroad demonstrate the extent of that deficiency. The first volume, The Underground Railroad from Slavery to Freedom (1898) by pioneering Underground Railroad historian Wilbur H. Siebert, is still a beginning point for many who investigate efforts to assist freedom seekers in the pre-Civil War Midwest. Siebert collected testimony from hundreds of participants and witnesses in the struggle and converted this documentary record into a broad and influential work that is still in print. Exactly two sentences in a work of 358 pages discuss the aid given to freedom seekers by Native Americans, in this case, the hospitality afforded at Chief Kinjeino’s village on the Maumee River in northwestern Ohio.

Fast forward nearly eleven decades to the second work, perhaps the most extensive and authoritative Underground Railroad interpretation since Siebert. Bound for Canaan: The Underground Railroad and the War for the Soul of America (2005) by journalist and popular historian Fergus Bordewich does only slightly better. It includes four sentences out of 439 pages on the assistance given to freedom seekers by Native Americans passing through the region, in this case, the aid provided to Jermain Loguen and John Farney in northern Indiana and Josiah Henson and his family in northwestern Ohio. Readers of these two volumes could be excused for thinking that there was little interaction between freedom seekers and Native Americans in the Midwest.

There are at least two primary reasons for the absence of Native Americans in the historiography of the Underground Railroad.

First, both freedom seekers fleeing slavery in the South and the Native Americans who assisted them in the Midwest came from oral cultures. Scholars of slave literacy estimate that only five to ten percent of those in bondage could read and write. Although the percentage might have been slightly higher among those who made their way to freedom, a small minority of freedom seekers had achieved literacy. Indians across the pre-Civil War Midwest also lived in primarily oral cultures. Scholars have noted that “oral histories were central to indigenous society,” making use of mnemonic devices and reflected in storytelling. As a result, both freedom seekers and Native Americans left a limited written record of their interaction.

Second, local histories, including the large volume of county histories produced across the Midwest in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, start the clock with white settlement, ignoring Native American contributions generally and particularly those after the War of 1812. In fact, most of these county histories make it seem as if Native Americans disappeared from the lower Midwest by the end of the War of 1812.

My own investigation of county histories for nearly two dozen counties in northwestern Ohio, an area where Native Americans were the primary population group until the 1830s, shows that Native Americans are largely excluded from this later history. When the Underground Railroad is mentioned, it consists of white settlers aiding anonymous freedom seekers and is completely a post-settlement phenomenon of the 1840s and 1850s. This is reflected as well in Siebert’s massive project in the 1890s. As a result, the interaction of freedom seekers and Native Americans in communities across the Midwest has been obscured.

In spite of the absence of Native Americans in the historiography of the Underground Railroad, a scattered documentary record exists to demonstrate that freedom seekers received significant assistance from Indians in the pre-Civil War Midwest. There are at least five major evidences of this interaction.

The first of these evidences is simple geography. Tiya Miles, who has written extensively about African American-Native American interaction, notes that “the routes that escaping slaves took went by these (Native) communities.” Examples abound, especially in the lower Midwest. The Michigan Road, a major thoroughfare for freedom seekers making their way through central Indiana, ran through or past dozens of Potawatomi villages north of the Wabash. Hull’s Trace and the Scioto Trail ran through or past Ottawa and Wyandot reserves, respectively, in northwestern Ohio. Another major trail ran through Shawnee villages in western Ohio, before reaching Ottawa villages at Lower Tawa Town and Chief Kinjeino’s Village on the Maumee River. From about 1800 to 1843, a maroon community of sorts existed at Negro Town in the heart of the Wyandot Grand Reserve on the Sandusky River. It was peopled by runaway slaves from Kentucky or western Virginia who had followed the Scioto Trail northward.

A second of these evidences can be found in the slave narratives, autobiographies written by freedom seekers after their escape from bondage. Several of these tell of assistance received from Native Americans. Two provide particularly instructive content about the Midwest. Josiah Henson’s narrative traces his and his family’s escape from Kentucky to Upper Canada (contemporary Ontario) in 1830, eventually taking them up Hull’s Trace through the heart of Indian Country in northwestern Ohio. There they were assisted by Native Americans (probably Wyandot) who fed them “bountifully” and gave them “a comfortable wigwam” to sleep in for the night.

The next day, their Indian companions accompanied them along the route for a considerable distance, before finally pointing them toward the port of Sandusky on Lake Erie, where they could take a vessel across to Upper Canada. Jermain Loguen’s narrative traces his escape with John Farney from Tennessee to Upper Canada in 1835 by way of central Indiana. North of the Wabash, they were aided at a number of Potawatomi villages, receiving food, shelter, and direction from their Indian hosts. Upon reaching Michigan Territory, they turned eastward and crossed into Upper Canada. Both Henson and Loguen later achieved literacy and became well-known black abolitionists.

A third of these evidences survives in Native American oral tradition. One of the best examples comes from Ottawa oral tradition in western Michigan. A story of helping twenty-one freedom seekers to reach Upper Canada was passed down through three generations of the Micksawbay family, before it was finally recorded in print by Ottawa storyteller Bill Dunlop in the book The Indians of Hungry Hollow (2004). The oral tradition recounts an episode in the 1830s that involved the group of freedom seekers, who had gathered at Blackskin’s Village on the Grand River. Ottawa elders, fearful that these runaways would be overtaken and captured by slave catchers, and sensing that sending them to Detroit was unsafe at the time, arranged for ten Ottawa men to accompany them overland to the Straits of Mackinac, where they were handed off to friendly Ojibwa. The latter took them across by canoe to Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, and then accompanied them overland, crossing into Upper Canada by way of Neebish Island. Oral history interviews with Native American descendants in the Midwest have also proven useful in establishing elements of this African American-Native American interaction.

A fourth of these evidences comes from the memoirs, letters, and journals of white traders, trappers, missionaries, and soldiers who lived in or passed through Indian Country in the Midwest and recorded their experiences in textual form. My own research in northwestern Ohio has located discussions of Native American assistance to freedom seekers in the memoir of trader Edward Gunn and the letters to Siebert by trader Dresden Howard, both of the Maumee River valley, and the letters and journals of Moravian missionaries and U.S. soldiers in the War of 1812 who recounted life in Negro Town. A particularly instructive example appears in the memoir of Eliza Porter of Wisconsin.

She and her husband Jeremiah, missionaries in Green Bay, cooperated with Native Americans on the Stockbridge reservation east of Lake Winnebago in aiding fugitive slaves making their way through eastern Wisconsin to Great Lakes ports in the 1850s. On one occasion, detailed in Porter’s memoir, they assisted a family of four runaways from Missouri in avoiding slave catchers and bounty hunters said to be “sneaking around” the reservation. The Stockbridge helped their guests make their way to Green Bay and gain passage on the steamer Michigan, which carried them to freedom in Canada West (formerly Upper Canada).

A final evidence appears in the bodies of freedom seekers and Native Americans and their descendants. This takes us into the realms of genealogy and the DNA record and particularly applies to those freedom seekers who sought permanent sanctuary in Native American villages in the Midwest. Native American genealogist Don Greene has found extensive evidence of African American ancestry among the Shawnee in the region. A case in point is Caesar, a Virginia fugitive who escaped across the Appalachian Mountains to the Ohio Country in 1774 and was adopted by the Shawnee. He married a mixed-race Shawnee woman named Sally and fathered children known to history as “Sally’s white son” and “Sally’s black son” due to their difference in hue.

The latter is still listed as “Sally’s black son” on the roll of Shawnee migrants removed from the reservation at Wapakoneta to the Kansas frontier in 1832. Similarly, researchers have suggested that the origin of the R-M 173 Y-chromosome among Native Americans, especially Ojibwa in the Great Lakes region, comes from the large number of runaway slaves settling among them. These are examples from Indian Country in the Midwest of what historian William Loren Katz labels “Black Indians.”

Some subjects of historical research can be substantiated by investigating a single archive or a few collections in related archives. The role of Native Americans in assisting freedom seekers in the pre-Civil War Midwest is not one of those subjects. The latter subject requires the historian to assemble an archive from a range of disparate sources. The evidence exists, however, to suggest that it can be done. Simple geography, a few slave narratives, Native American oral tradition, dozens of scattered documents by particularly involved and insightful whites in Indian Country, and genealogy and the DNA record substantiate Tanner’s 2002 observation about Native Americans and the Underground Railroad in the Midwest.

Roy E. Finkenbine is Professor of History and Director of the Black Abolitionist Archive at the University of Detroit Mercy. He is currently engaged in a book project tentatively titled Fugitive Slaves in Indian County: Crossings and Sanctuaries.