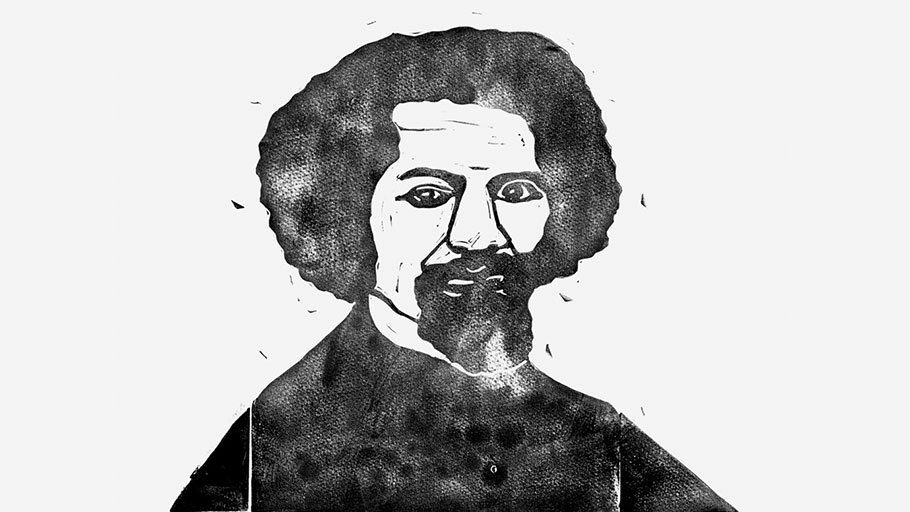

No one was ever a more critical reader of the Constitution, or a more compelling advocate of its virtues, than Douglass.Illustration by Hugo Guinness

He escaped from slavery, and helped rescue America.

By Adam Gopnik, The New Yorker —

Frederick Douglass, who has been called the greatest American of the nineteenth century, grew up as a slave named Frederick Bailey, and the story of how he named himself in freedom shows how complicated his life, and his world, always was. Frederick’s father, as David W. Blight shows in his extraordinary new biography, “Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom” (Simon & Schuster), was almost certainly white, as Douglass knew early on, and there is something almost cruelly parodic in the grand name the child slave was given: Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey. Escaping to freedom in 1838, at the age of twenty, and needing a new name—in part as a declaration of a reinvented self, in part for the practical necessity of eluding the slave-catchers—he chose to become Frederick Douglass, in honor of a character in a Walter Scott poem. (He added an extra “s” for distinction.)

What’s curious is that this was a completely Southern choice, a tribute to the culture he was escaping. The South, as Mark Twain protested at length, had long been hostage to a cult of Walter Scott’s neo-medievalism, one of the opiates of Southern “gallantry” that justified the concentration-camp culture as a leisurely and gracious one, a myth so durable that it shaped the most successful American movie ever made, “Gone with the Wind.” But the choice is also a reminder that the wind in Romanticism, and in Walter Scott, could blow both ways, toward liberal nationalism and self-renewal as well as toward feudal nostalgia and hierarchy. Douglass’s new name was as much a rejection of his slave name as was Malcolm X’s rejection of his birth name, Little—but in this case the chosen name denoted not an absence but a presence. The name he chose inscribed him within a cultural tradition that he had been forced to inherit and chose to remake. This insistence on seeing past the evils of the Enlightenment in search of the light that was still left there made him one of the most radical readers of the American nineteenth century. No one was ever a more critical reader of the Constitution, or, in the end, a more compelling advocate of its virtues.

With Douglass, then, we have everything and its opposite—the slave wielding a sword of vengeance against the South who adopted the South’s mythology for his own; the militant prophet of the truth that no compromise with slavery was possible who became a central pillar of pragmatic politics in the postwar era. In telling this great story, Blight, a historian at Yale, confronts one great difficulty: Douglass himself wrote his own life three times, each time thrillingly well, though each time with a slightly different purpose. Like the Gospels, each is written with a different ideological agenda. In 1845, “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave,” was written as a straightforward abolitionist horror story, albeit an exceptionally humane and potent one. Ten years later came “My Bondage and My Freedom,” a fuller and more nuanced-novelistic account of the same story. And then, in 1881, when he was in his sixties, he published “Life and Times of Frederick Douglass,” in which this man, who had watched the ships go by in the Chesapeake Bay with a desperate sense of disbelief that anyone or anything in the world could be so free, was able to report on his journeys to Cairo and Paris and his reception in both as a man of state and of letters.

The prose style in the three memoirs alters under the pressure of the changing agenda: the first time pained and urgent, the second subtler and more considered, the last orotund and outward. Yet, as Blight shows, the tale Douglass wove about himself, from the first to the last volume, is remarkably faithful to what can be dug up independently about the facts of his early life. So Blight’s biography, particularly in its early pages, is necessarily a kind of palimpsest: he dives back and forth beneath Douglass’s texts, sifting and sorting and weaving.

The story, simply told, is that Douglass was largely spared the worst of slavery by inhabiting its more familial edges, at a time when who owned you and where you were owned shaped the course of your life as someone else’s property. After he had been passed from his brutal first master to the man’s kinder son-in-law, Thomas Auld, the transforming event of Douglass’s life was his arrival in Baltimore, at the age of eight, to live with members of Auld’s family. City slaves were better treated than country slaves. “A city slave is almost a freeman, compared with a slave on a plantation,” Douglass wrote. “He is a desperate slaveholder who will shock the humanity of his non-slaveholding neighbors with the cries of his lacerated slave.” As a child, he had, unusually, been treated more or less as an equal playmate of his first master’s son, and soon Sophia Auld, the wife of Thomas’s brother, began to teach him to read and write.

Absolute power, even when well meant, always becomes arbitrary. Sophia first took immense pleasure at Frederick’s celerity as a pupil, and then, under the pressure of her husband’s disapproval (“If you teach that nigger how to read, there would be no keeping him”), turned violently against the boy’s education. Frederick persisted, trading bits of bread with street urchins for secret reading lessons. Here, as elsewhere in his life, he defeated the expected racism of his fellows by the sheer magnetism of his manner.

He was also able to take advantage of the oppressor’s hypocrisy: slavery being a Christian institution, it was important to expose the slaves to the Gospels. This meant that the innocent business of studying the Bible could be turned to the subversive aim of acquiring literacy. Having learned to read by literally buying words, Douglass had an intense sense of the power of language, of the double meanings of individual words; irony was ingrained in him. He heard the word “abolition,” for instance, as a mysterious, forbidden incantation; he didn’t know precisely what “abolition” meant, but he could tell from the murmur around it that it mattered enormously.

He loved Baltimore, but was wrenched out of it when he was fifteen and sent a year later to be “broken” in the backwoods by a cruel overseer named Edward Covey. Making up his mind that he would die trying to sustain his manhood, he attacked Covey, with the result, by no means guaranteed, that Covey backed off. Douglass thought this a proof of the powers of resistance, but he also knew that such resistance usually brought instant death or else shipment down to the plantations of the Deep South—a living death. In fact, he was shipped off to the backwoods, where he tried and failed to escape. Then a remarkable piece of good fortune came his way. Auld, for reasons still mysterious—from humanity or guilt or a buried sense of kinship?—meekly took him back to Baltimore and promised to free him after a seven-year hitch. It was, as Douglass came to recognize, the great salvation of his life. In 1848, he wrote an open letter to Auld, saying, “I entertain no malice toward you personally. . . . There is no roof under which you would be more safe than mine, and there is nothing in my house which you might need for your comfort, which I would not readily grant. . . . I am your fellow-man, but not your slave.” That letter was a kind of propaganda piece, to show the slave’s moral superiority to his master, but it was sincere as well as shrewd.

In Baltimore that second, salvaged time, he fell in love with a free black woman, Anna Murray. It is still a little hallucinatory to be reminded that, in the border states, free blacks, second-class citizens but citizens still, lived side by side with those who were property. Murray emboldened Douglass to escape and he fled to freedom disguised as a sailor. The account of his flight north stops one’s heart to read, so near did he come to apprehension. (A worker whom he knew from the docks saw him, recognized him, and—kept silent.)

In 1841, three years after he got a job as a laborer in New Bedford, Massachusetts, where he made a name speaking at the local A.M.E. Zion church, he was brought to an abolitionist meeting in Nantucket, a booming whaling port, and made an impromptu speech that changed history. No one had ever heard an ex-slave speak with such precision and eloquence about his experiences. The eminent white abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison and his followers pressed him into service as a speaker, and Douglass spent the next fifteen years riding trains from one abolition meeting to the next while Anna, now his wife, who had come north after him, waited in New Bedford and raised an ever-growing crop of children. (They had five in all, including three sons who served in the Civil War, one of them surviving, improbably, the massacre of Robert Gould Shaw’s regiment at Fort Wagner.)

Like many other young and still unformed activists who discover in themselves a gift for oratory, Douglass had to self-educate even as he was speaking. Young orators’ tongues are formed before their minds are set. This happened to Martin Luther King, Jr., who had to inhabit a leadership position that he was not yet fully prepared to assume, as it did to Emma Goldman, an immigrant girl who became Red Emma almost before she mastered English. (In a more benevolent manner, it happened to Barack Obama—one eloquent speech turning him from a relatively green politician into a plausible Presidential candidate.) In each case, the challenge is to keep one’s independence, and one’s head, as others are trying to turn you into their megaphone.

Douglass passed from slave to celebrity in about a year and remained one for the rest of his life. He began the small list of people who are, in effect, the face of their movement. Gloria Steinem was not the most important feminist thinker of her time, or its most significant organizer, but she was the face of American feminism, for a reason. She embodied the reality, confounding to sexists, that a woman who looked like her could be a radical egalitarian about gender. Douglass embodied the reality, confounding to racists, that a black man could be charismatic, imposing, educated, and a voice for absolute emancipation. Douglass’s charisma—along with his good looks—wasn’t incidental. He was one of the most photographed men of the nineteenth century, as photogenic as Jack Kennedy a century later. In the photographic portraits (collected and contextualized in a 2015 volume titled “Picturing Frederick Douglass”), he sometimes looks like a fiercer George Washington—Roman nose, intense scowl of virtue, swept-back classical hair. In a new culture of reproduced images, these things counted.

Douglass’s personal charisma involved, too, an unashamed sexual presence. His slave narratives are strikingly frank about the terrible erotics of slavery, and of black-white race relations, in a way that would not be acceptable in progressive discussions of race until the nineteen-sixties. In his first two memoirs, he writes bluntly about forced sexual relations between slave and master, and what perverse family relations they produced, including the fact that rape was turning the black slave population half white:

If the lineal descendants of Ham are only to be enslaved, according to the scriptures, slavery in this country will soon become an unscriptural institution; for thousands are ushered into the world, annually, who—like myself—owe their existence to white fathers and, most frequently, to their masters, and masters’ sons. The slave woman is at the mercy of the fathers, sons or brothers of her master. The thoughtful know the rest.

His early memoirs find a balance between outrage and subtle irony—those angry, understated phrases: “an unscriptural institution”; “the thoughtful know the rest”—in describing the wrenching effects of slavery on the human soul. Pointing out that one would expect slave masters to be kind to their own children, he coolly analyzes the truth: “Men do not love those who remind them of their sins unless they have a mind to repent—and the mulatto child’s face is a standing accusation against him who is master and father to the child. What is still worse, perhaps, such a child is a constant offense to the wife. She hates its very presence.” What would be a buried subject in most American writing about black-white relations was with Douglass overt, in a way that must have intimidated his followers and inflamed his haters.

Four relationships—three with white American men, one with a European woman—shaped Douglass’s mature life and mind. He had a tutelary and then an adversarial relation with William Lloyd Garrison; then an admiring and allergic relation with John Brown; next, a prophet-and-politician relation with Abraham Lincoln; and, finally, a deep, romantic relation with a woman named Ottilie Assing. (Throughout this time he made his living, as best he could, as a miscellaneous journalist, beginning an anti-slavery weekly first called, poetically, the North Star and then, tellingly, changed, for branding purposes, to Frederick Douglass’ Paper.)

The story of Douglass’s relationship with Garrison is one of the key stories in American political history. They met and became friends at that 1841 gathering in Nantucket. Garrison, the most famous abolitionist of the period, was the headliner when Douglass was asked to tell the story of his life. Overwhelmed by Douglass’s eloquence, Garrison asked the crowd, “Have we been listening to a thing, a piece of property or a man?” Douglass went on the road as a Garrisonite.

Less than a decade later, they broke, bitterly and for life. Some of the bitterness arose from Douglass’s uneasy sense that he was not so much being used as being put on display. One wonders if Ralph Ellison was aware of Douglass’s relationship with Garrison when, in “Invisible Man,” he wrote about his unnamed narrator’s relationship with “the Brotherhood,” a version of the Communist Party. They’re strangely similar: the black man discovers a gift for oratory, is instantly pressed into propaganda service by a white radical organization, and has a deeply ambivalent relation with his new white friends, who are just a little too much like his old white masters.

Douglass’s break with Garrison also derived from a decisive intellectual difference, one that still sculpts American politics—with the irony that the white crusader was the more conventionally radical actor, and the black ex-slave seemingly the more “moderate.” Garrison was both a pacifist and a moral secessionist. He believed that the Constitution was so deeply implicated in slavery—including its creation of the small-state-favoring Senate—that it could not be salvaged. Douglass came to believe that the Constitution was a good document gone wrong—that, in its democratic premises, it breathed freedom, and that it needed only to be amended to be restored to its first purposes.

Douglass most forcefully offered this insistence in his 1852 “Fourth of July” speech in Rochester. It is a masterpiece of startling argumentative twists. He begins with unstinting praise of the values and character of the Founding Fathers—the only forewarning of dissent being his speaking of the events of the seventeen-seventies in the second person: your Founders did this . . . yourhistory says that. Then he makes his thundering turn: “The existence of slavery in this country brands your republicanism as a sham, your humanity as a base pretense, and your Christianity as a lie.” Finally, he makes a still more surprising swerve, back toward the American center: the Constitution is solid, all that needs fixing is our way of reading it. “Interpreted as it ought to be interpreted, the Constitution is a glorious liberty document. Read its preamble, consider its purposes. Is slavery among them? Is it at the gateway? or is it in the temple? It is neither.”

The constitutional issue was, and remains, epic. All of American liberalism remains at stake in this choice—it is what divides Obama from Cornel West and his other critics on the left. For Garrison, the failure of liberal constitutionalism to achieve its stated aim was a reason to abandon it. For Douglass, the failure of liberal constitutionalism to achieve its stated aim was a reason to re-state the aim more forcefully and more inclusively. If the aim was in the document, the arc could yet be completed. He thought the aim was there, and the arc was possible.

The philosopher Robert Gooding-Williams, an astute reader of Douglass, sees him as drawn to the “possibility of refounding the Union on the basis of a reconstituted practice of citizenship.” Douglass’s belief in the integrity of the American Constitution made him, ironically, less willing to wait for legislative remedies and readier to use violence against the slave establishment. This became Lincoln’s reasoning, too, evident in his legendary speech at Cooper Union, in 1860: the historical evidence showed that the signers of the Constitution considered slavery a national question, up for national debate. It wasn’t a local or a states’-rights question. Wrongly decided once, it was still on the agenda of the nation as a whole. In the name of the Constitution, slavery was to be assaulted frontally. (How frontally Lincoln could not decide, until events overtook him as President.) For Douglass, this urge to fight for principle, while making sure that the fight could be won, shaped his strange push-and-pull relationship with John Brown, in itself a mini American epic.

As Blight relates, Douglass was, in the eighteen-fifties, drawn by Brown’s courage during the Kansas question—the question of whether slavery was to extend into the new territories—and by the implacable nature of his antislavery views. Where even the Garrisonites condescended to blacks, Brown, as the Harvard historian John Stauffer showed in “The Black Hearts of Men” (2002), envied the courage and “manhood” of the escaped slaves, and was almost ashamed of his own whiteness. Yet Douglass was repelled by Brown’s fanaticism: morally clear-eyed on the subject of slavery, Brown was crazy on the subject of what to do about slavery, moved by bloodlusts and Biblicism and incapable of reasoning about means and ends. Douglass dallied with Brown and then, abruptly, withdrew his support from the Harper’s Ferry raid. Simple arithmetic, he saw, meant that it would achieve nothing and endanger the lives of any slaves who participated. Violent means would be necessary, but violence was justified only when it had a chance to prevail.

After the disaster of Harper’s Ferry, some officials in New York tried to have Douglass arrested as a conspirator, and he prudently fled, first to Canada and then to Britain. It was a mistake on the part of his persecutors to force him into exile, however temporary. A huge hit as a lecturer in England and Scotland, he rallied the already strong antislavery forces there.

Moral consensus can shift with enormous rapidity. Not so very long ago, it was acceptable to cast the American Civil War as a tragic clash between two decent sides. In Ken Burns’s 1990 PBS series on the war, Shelby Foote declared, speaking through his soft beard with his gentle drawl, that the problem was that the North and the South somehow couldn’t find a compromise. It has since become harder to deny the truth that slavery was the sole cause of the war. What made war inevitable, then, was the election of President Lincoln, a single-issue candidate who had made his name by calling for an end to slavery’s extension and by recognizing it as an absolute evil. The one conceivable compromise that might have been tried was a gradual program of subsidized emancipation, but, as Lincoln discovered from his correspondence in early 1861 with Alexander Stephens, the eventual Vice-President of the Confederacy, the Southern ruling class had made up its mind: slavery or secession.

While slavery was the war’s sole cause, however, it was not the war’s sole or even its most important rallying cry. To the antislavery cause was added the pro-Union cause, a narrowly nationalist crusade. This aspect of the President’s war-making is why Edmund Wilson impatiently compared Lincoln to Bismarck—both seen as iron-hearted nationalists who taught their people to die for the idea of national greatness. And there’s no doubt that “We won’t let you Rebs walk away with our one country!” was a more motivating cry at Gettysburg than “You must never again keep slaves!”

Douglass came to see that Lincoln had wrapped the right cause around the wrong cry. The ingenuity of the Gettysburg Address as a forensic argument lies in the way it made the two causes—nationalism and emancipation—seem one. The nation was born in the view that all men are created equal; slavery denies that view; if we lose the war, it shows the world that a nation with that premise cannot survive unfragmented; and therefore fighting for the Union is the same thing as fighting for its first principles. Douglass admired the somewhat sophistic logic.

During the war years, he spent a surprising amount of intellectual energy opposing what now seems to us an obvious chimera—a plan to resettle ex-slaves outside the United States, in Central America or the West Indies or Africa. Though Lincoln sometimes seemed sympathetic to this idea, “colonization” was always unrealistic. But it wasn’t inherently a racist scheme, and not a few black leaders, including the great abolitionist Martin R. Delany, advocated what was, in effect, a form of black Zionism. Why, then, did Douglass think it so important to battle? It was because Douglass saw culture and civilization almost entirely in what we now call Eurocentric terms. He took his language and his lore and his moral categories from the Bible, Shakespeare, Milton, Scott. He did not see these as the alien property of white people. He thought they were his, to own and to alter.

Douglass’s relationship with Lincoln throughout the war has been beautifully detailed in “Giants” (2008), another book by John Stauffer, and Blight largely follows the same outlines of the dance between crusader and politician. Douglass was at first impatient and mistrustful of Lincoln, became somewhat more empathetic concerning his political struggles, and ended being a full-hearted admirer, enthralled by the intended scope of emancipation. Lincoln, for his part, came to understand that Douglass’s moral vision was impeccably correct—and a critical undergirding for Lincoln’s increasingly militant views. At the second Inauguration, Lincoln greeted Douglass at the White House reception not as “Mr. Douglass” but as “my friend.”

It was during these years that Douglass brought his fascination with the European Romantics to a head, by becoming involved with one. Ottilie Assing was a German intellectual who came to Hoboken in the eighteen-fifties. Although her father’s origins were Jewish, she considered herself German, and at a time when German in America was what Jewish would be later: the crucial liberal ethnicity. She interviewed the famous ex-slave in his Rochester home in 1856, fell passionately in love with him, even sometimes sharing the home with Anna and the rest of the Douglass family.

Douglass’s biographers, including Blight, are uneasy about this relationship. On the one hand, our feminist principles want to make of Assing a model European woman of mind, a suitable intellectual partner for Douglass, a Harriet Taylor to his John Stuart Mill—which indeed she was, broadening his knowledge of, among other things, German poetry and philosophy. At the same time, the characterization feels unkind toward Anna Douglass, who had taken unimaginable risks in order to help Frederick escape slavery. Though Blight is cautious about drawing firm conclusions, it seems clear that Douglass and Assing had an erotic relationship. She wrote to her sister about how happy she was, even though the “external situation remains less than perfect”; and she wrote also of how it feels “when one stands in such intimate relation with one man, as is the case with me in relation to Douglass.” When, later, she went back to Europe, she had his letters burned, and eventually committed suicide by cyanide, at least in part from loneliness.

She brought poetry into his life in every sense—with the reading she shared but also through the rich fantasy she created in which they would start a free, itinerant life together in Europe. As Blight writes, “Ottilie almost never gave up on her quest of drawing Douglass off to a new life in Europe; like spring itself, it was her annual recurring fantasy.” This plan never seems to have existed at more than the level of fantasy—but then the level of fantasy is one of the most important levels at which things can exist. Elsewhere, she compared herself to another Ottilie, in a Goethe novel, who, Blight notes, “finds a tragic fate due to a form of spiritual adultery.” We can overlook how exhausting commitment to a great cause can be, and Douglass had become bound to his. The dream of escape to the Alps with Ottilie was something to be free for.

Douglass’s political life after the war’s end and Lincoln’s assassination may seem anticlimactic, and yet in many respects it is as important as what preceded it. He became, in one view, a conventional party politician. But there is a more positive way to see this migration from militancy. Stauffer’s “Giants” showed us how much Douglass’s prophetic force poked and prodded Lincoln toward righteousness, but Douglass himself was deeply affected by Lincoln’s example of the power of liberal party politics to make real change happen. He became a proud pillar of the Republican Party—essentially, the same baggy assemblage of minorities and progressives and city people (and neoliberals) that we find in the Democratic Party today. Even as Reconstruction failed and Jim Crow overtook the South—a reality that Douglass spoke up against as passionately as he had spoken up against slavery—he devoted most of his time to the construction of black institutions. He helped build colleges; there was also a Freedman’s Savings Bank, which, sadly, failed after he had agreed to run it. He received (to the dismay of many black contemporaries) a patronage post, as the U.S. Marshal of Washington, D.C., and was not above passing along a bit of juice to friends and family.

Blight has certainly written, in the book’s texture and density and narrative flow—one violent and provocative incident arriving right after another—a great American biography. But when it comes to the postwar Douglass he perhaps succumbs to a moral anxiety that seems endemic in American academia, taking an ambivalent tone about Douglass’s seemingly more conventional postwar path, and about aspects of Douglass’s engagement with other kinds of liberation movements.

This is particularly true of his engagement with women’s suffrage. We would have liked the struggles against the subjugation of women and of blacks to swim along in tandem. And to some degree they did. Douglass was one of the few men present at Seneca Falls in 1848, when Elizabeth Cady Stanton helped launch the modern American feminist movement. “The history of the world has given to us many sublime undertakings, but none more sublime than this,” he said later. “It was a great thing for humane people to organize in opposition to slavery; but it was a much greater thing, in view of all the circumstances, for woman to organize herself in opposition to her exclusion from participation in government.” (A greater thing, he thought, because it was less self-evidently cruel and more insidiously oppressive.) But, as the war ended and the eighteen-sixties progressed, there were deep differences between them, which, by our standards, were flattering to neither.

Douglass insisted that the Fifteenth Amendment and other protections of black suffrage were essential, even if they excluded women. In 1866, he wrote that, with women, “it is a desirable matter; with us it is important; a question of life and death,” and he made reference to recent massacres of unprotected “free” blacks in New Orleans and Memphis. Later in the decade, he insisted, “When women, because they are women . . . are dragged from their houses and are hung from lamp-posts; when their children are torn from their arms, and their brains bashed out upon the pavement . . . then they will have an urgency to obtain the ballot equal to our own.” Northern middle-class white women, in this view, were free riders on the black man’s struggle for liberation, with incomparably lower risks. Their “husbands, fathers, and brothers” could already protect them. (Intersectionality having not yet arrived, neither Douglass nor the white suffragists talked much about the special predicament of black women.)

Stanton, like her fellow-campaigner Susan B. Anthony, thought that Douglass failed to grasp that they were not a minority seeking protection by the ballot but a majority forever excluded from any exercise of political power, and declared that a government with the participation of black men as well as white men would merely “multiply the tyrants.” They were incensed by the condescension they detected in him. And both Douglass and Stanton felt free to use the Drunken Pat argument, asking why the feckless, inebriated Irish immigrant had the vote when—depending on who was arguing—black men or white women didn’t. None of it is to our taste: Douglass insulted women, Stanton insulted blacks, and both felt free to insult the Irish.

Yet we need to be charitable about the moral failings of our ancestors—not as an act of charity to them but as an act of charity to ourselves. Our own unconscious assumptions and cultural habits are doubtless just as impregnated with bias as theirs were. We should be kind to them, as we ask the future to be kind to us. To take a small example from this biography: Blight celebrates Douglass’s escape from the South to the whaling town of New Bedford, where he first came into contact with the broader abolitionist circles. He doesn’t mention the fascinating figures of the black whaling captains, whaling being one of the rare professions in pre-Civil War life where black men were sometimes trusted in positions of command. But the whalers participated in acts of unimaginable cruelty inflicted on creatures capable of feeling pain and fear—and future generations might well become as intolerant of cruelty to animals as we are of cruelty to people. As for the ethnic joking that pains Blight, it was an assertion of Americanness: no longer an outsider, Douglass could make after-dinner jokes about the Irish, right along with the rest of his countrymen. (To add to the pile of ironies, in 1884, a couple of years after Anna’s death, he married another women’s-rights campaigner, and a patrician white one at that, Helen Pitts, previously his secretary. Like Assing, she was fiercely devoted to him, and they did the world travelling that had been mere fantasy before.)

Much of the last two decades of Douglass’s long life, before his death, in 1895, was spent on a kind of permanent victory tour, receiving honors while exasperating younger black leaders who, in the time-honored tradition, thought that the grand old man was far too grand and far too old to do the necessary work. But he never became morally inert. In 1877, Douglass sought out Thomas Auld, who was dying, to forgive him. “Frederick,” Auld said, “I always knew you were too smart to be a slave, and had I been in your place, I should have done as you did.” “I did not run away from you,” Douglass replied. “I ran away from slavery.”

That the distinction seems less clear to us—what was Auld but the living face of slavery?—than it did to Douglass is a sign of the complexity of the relationship, and also of the power of the Christian doctrine of forgiveness to penetrate a sensitive mind. For Douglass identified himself as a Christian throughout his life, and his gesture reminds us that slaves absorbed and reimagined the religion of their oppressors in their own morally original terms, as a permanent bulwark against persecution. Even during the reign of white terror that replaced the plantation concentration camps, the black church became the chief reservoir of social capital, and remained so right through Dr. King’s time—one more way in which Douglass’s life encompassed so much of what was to come.

In the end, Douglass fascinates us because he embodies all the contradictions of the black experience in America. A case can be made for him as the progenitor of the pragmatic-progressive strain that leads to Dr. King and, even more, to Bayard Rustin and Obama—disabused of illusions, but insistent that with time the Constitution can be realized in its fullness and that democratic politics are the way to do it. This Douglass is the friend of Lincoln, the man who sustained the necessary relations with institutional power—as Dr. King would do, however guardedly, with Kennedy and then with Johnson. Douglass understood that African-Americans were too small a minority to act without allies. A related pragmatism, prominent in his later writings, became the model of “self-reliance” of the kind that inspires one conservative strain of African-American thought, from Booker T. Washington to Clarence Thomas.

Yet Douglass can also be seen as the father of the most militant strain of resistance, the kind that insists on the uncompromising rejection of racism, with violence as a recourse when necessary. His confrontation with the brutal slave-breaker Covey is still a model of “manhood,” of self-assertion in defiance of death. Lincoln remains the saint of American democracy, yet his ascent from the backwoods to the White House was, for all its rigors, a far easier ride. Lincoln read in the midst of farming chores; Douglass learned to read at the risk of his life. He had farther to go, and went wider in getting there. Such are the multitudes he contains; he is far from a nineteenth-century figure alone. In his legacy as prophetic radical and political pragmatist, in the almost unimaginable bravery of his early journey and the resilience of his later career, in his achievements as a writer, activist, crusader, intellectual, father, and man, the claim that he was the greatest figure that America has ever produced seems hard to challenge.