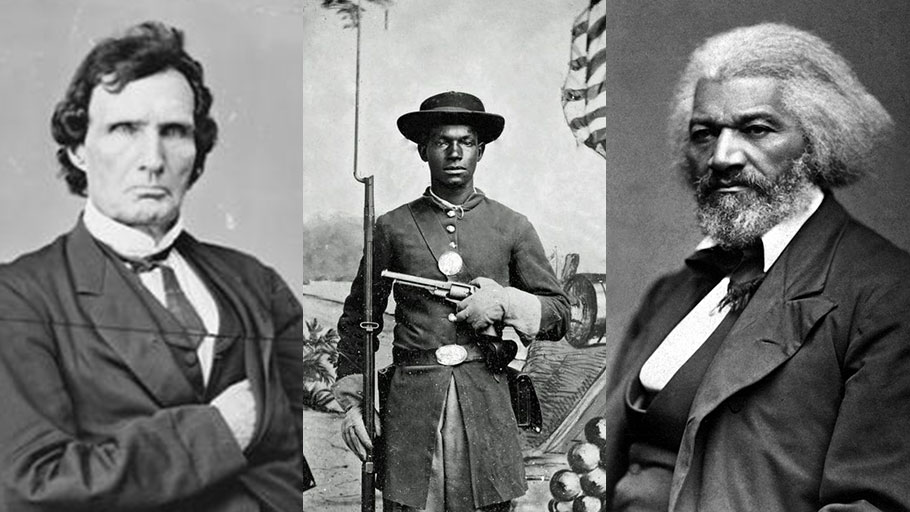

Left to right: Radical Republican Thaddeus Stevens; an African-American soldier in the Union Army; abolitionist Frederick Douglass

The ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment marked a turning point in U.S. history. Yet 150 years later, its promises remain unfulfilled.

The ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment on July 9, 1868 was a turning point in United States history. Arriving at the height of Reconstruction, the amendment marked the first time the U.S. Constitution explicitly addressed the question of who qualified as an American citizen. Southern African Americans who had won their freedom in the Civil War were, in effect, forcing the country to redefine its identity, and to make good on its promise of universalism. The vision of emancipation expressed in the Amendment was expansive, serving to enshrine in law the principles of due process and equal protection as well as the basic right to citizenship.

Yet, a century and a half later, its goals remain unfulfilled. Movement leader Reverend William J. Barber II argues that the task facing the United States today is nothing short of a “Third Reconstruction,” drawing on the legacies of both the Reconstruction era of the 1860s and 1870s and the civil rights movement, or “Second Reconstruction,” of the 1960s and 1970s. In making these historical connections, today’s activists can understand that they aren’t alone, and draw both lessons and spiritual strength from those previous eras of promise and dashed expectations. If the left wishes to make the most of the Third Reconstruction—not just defeating a revanchist right wing at the polls but fundamentally changing the nation for the better—we can draw important insights from these two previous eras of civic revolution.

Allen C. Guelzo’s recent book Reconstruction: A Concise History (2018) reminds us that deeming Reconstruction a “failure” overlooks the many successes of the period. Many historians focus on the fact that Radical Reconstruction’s greatest victories—the ratification of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth amendments, along with the transformation of the idea of citizenship into how we understand it today—were achieved over a relatively short period (1865 to 1870), only to be met with decades of vicious backlash. The rise of “redeemer” Democratic governments in the South, white supremacist forces who refused to countenance equal rights for African Americans, and were aided and abetted by most white citizens below the Mason-Dixon line, destroyed the brief moment of promise in the South. By 1877, the Reconstruction dream of biracial governments in the South—as emerged in South Carolina, for example, beginning in 1868—was dead. But it laid a foundation for the work of future activists by enshrining in the Constitution provisions that protected civil and political rights from discrimination due to skin color or ethnicity—if only the federal government would enforce them. The nation did not realize even a shadow of the promise of Reconstruction until the landmark civil rights victories of the 1960s.

The Second Reconstruction—a name given to the civil rights movement by historian C. Vann Woodward and embraced by many activists—encapsulated how many viewed the clash between African Americans seeking freedom and the white supremacist power structure of the South. Both eras saw considerable political and social upheaval in the South. However, most activists in the civil rights movement recognized they weren’t just fighting against Jim Crow segregation in the South, but against a nationwide system of discrimination that had to be dismantled. Local civil rights campaigns in cities such as New York, Boston, Detroit, and Philadelphia should be spoken of in the same breath as Montgomery, Birmingham, Selma, and Albany. Activists today, too, have shown a savvy understanding of how racist policies have taken hold from Wisconsin to New York to North Carolina—in red, purple, and blue states alike.

During the Reconstruction period, African Americans fought not only for political and economic rights in the American South, but also for civil rights in the North. The assassination of civil rights activist Octavius Catto in Philadelphia in 1871 is a testament to this fight. Catto was pivotal in raising African-American regiments for the Union Army during the Civil War. After the war, he campaigned for desegregated trolley cars in Philadelphia. Murdered on election day in 1871 for his forceful civil rights advocacy, Catto was honored with a statue in Philadelphia only in 2017—making him the first African American to be honored with a public monument in that city. The struggle for civil rights by Catto and others in the North during Reconstruction should remind us that the fight for freedom has always been a national one, even when public memory only focuses on the Southern front of that contest.

Even William Barber’s own biography points to links between the three Reconstructions. Barber’s father grew up in Plymouth, North Carolina, a place where African Americans still retained some economic and political freedom well after the end of Reconstruction. Barber’s parents were called back to North Carolina to integrate local schools as teachers, while Barber himself participated, as a second-grader, in the integration of a local school in the 1960s. The story of Barber’s family—not to mention that of many other African Americans—showcases a history of finding ways to get ahead during brief moments of political freedom in the United States, then bracing for the worst during the long nights of racist backlash.

We should also remember that each of the three Reconstructions, while revolving around the links between race and citizenship in American society, were concerned with two other questions as well: the role of gender and the clash of class interests. Movements for race, class, and gender equality did not always work in harmony: in the late 1860s, the fight over women’s suffrage dominated headlines and became a point of divergence between activists primarily concerned with securing the political power of African Americans in the South, versus gaining voting rights for white women across the nation. (“I will cut off this right arm of mine before I will ever work or demand the ballot for the Negro and not the woman,” Susan B. Anthony famously told Frederick Douglass in 1866. Douglass, for his part, said in 1868: “I have always championed women’s right to vote; but it will be seen that the present claim for the negro is one of the most urgent necessity.”) A century later, as the tail end of the civil rights movement coincided with the rise of second-wave feminism, the divisions were less acute—many leaders of the feminist movement had been galvanized by their experience in the civil rights revolution—but nevertheless resurfaced in different forms.

Today, of course, the rise of Black Lives Matter and a “Third Reconstruction” dedicated to safeguarding voting rights has coincided with a deepening women’s movement—for reproductive freedom and against Donald Trump’s policies as well as popularization of sexism and misogyny. Likewise, the rise of movements such as Occupy Wall Street and the Fight for $15 in the last decade parallel the rise of labor activism during the Reconstruction era, or the oft-forgotten but crucial labor strikes of the late 1960s.

What we should take from the idea of a Third Reconstruction is an awareness of how issues of race, class, and gender continually intersect to shape people’s lives. Queer African American women being at the forefront of Black Lives Matter—and making it clear that their multifaceted identities informed their leadership—is but one example of intersectionality in the Third Reconstruction. Another is the success of the Moral Mondays movement, led by Rev. Barber in North Carolina, which has championed abortion rights and voting rights, environmental justice and racial justice alike, all while fighting cuts to social services and a raft of discriminatory laws like the state’s notorious “bathroom bill,” HB2. The same spirit carried through the Poor People’s Campaign of this May and June, again led by Rev. Barber and channeling the legacy of Martin Luther King’s 1968 campaign of the same name.

In each of the previous two Reconstructions, an inability to unite across various identity fault lines contributed to the collapse of the progressive insurgency. The early labor unions of the 1870s just weren’t powerful enough to unite with the vibrant political movements below the Mason-Dixon Line—often led by African Americans—that promised to change the South forever if not for anti-Republican guerrilla warfare and determined white Democratic resistance. The Panic of 1873 galvanized labor activists and sparked demonstrations for public relief, as desperate farmers tried to fight off debt. But these groups lacked the political power to mobilize together. Nor were there serious attempts to link politically with African Americans in the South who were squeezed by both racism and the worsening economic crisis of the 1870s. In the 1960s, fractures among the left, combined with the politics of white backlash, pushed back a more radical human rights revolution, as captured in the Poor People’s campaign that King was planning when he was assassinated. State repression, backlash, and internal divisions also destroyed the growing Black Power movement, which in places like Chicago linked up with poor whites through the Young Patriots organization and promised a multiracial assault on white supremacy.

The backlash to both previous Reconstructions is also a bitter reminder of the need for economic and social justice organizers to be ready—and, indeed willing—to endure difficult political times. American history is punctuated by many moments of conservative retrenchment, threatening to subsume the small number of hopeful progressive moments. Much of the country’s history contains elements of both: after all, Reconstruction coincided with the dawn of Gilded Age, a period where unfettered capitalism unleashed an economic boom along with gaping inequality and new levels of corruption. Titans of industry—the infamous “robber barons”—cast their shadow over city, state, and federal governments alike. Corruption marred Reconstruction governments in the South, too, and opponents of black emancipation used their example to claim that African Americans were incapable of self-government. (Such an account, of “carpetbaggers” and “scalawags” conspiring with freed African Americans to destroy the noble South, lies at the heart of the Reconstruction portion of the 1915 film Birth of a Nation.) Distrust of what the government could accomplish in the 1870s was given form both by Reconstruction’s inability to forcefully take hold in the South, and by the corruption at various levels of government. By the turn of the twentieth century, movements on behalf of economic freedom—Populism and the labor movement—had either been decisively defeated or were in retreat. The battle for racial equality, too, took severe blows as African Americans lost their voting rights across the South and Jim Crow laws were instituted to further harm black political, social, and economic power.

The end of the Second Reconstruction coincided with the collapse of New Deal liberalism and the rise of the New Right in the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s. While the activists who carried the torch of the Second Reconstruction made remarkable gains—a record number of African-American elected officials in the South, gaining national support for sanctions against Apartheid South Africa in the 1980s, and the declaration of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s birthday as a national holiday in 1983—they also had to scramble to protect affirmative action and fight against the erosion of the Voting Rights Act.

A reasonable question can be asked: are we in the middle of a Third Reconstruction, as William Barber has suggested, or in the early stages of a “Second Nadir” of African-American history? The First Nadir, as it was dubbed by historian Rayford Logan, stretched from roughly 1890 until 1930. That was the lowest point of African-American political power in the United States since the abolition of slavery, culminating in both parties ignoring the black vote in the 1928 election and W.E.B. Du Bois proposing that African Americans had little to vote for in either party. Historian Nathan Connolly proposed in the pages of the Boston Review’s special issue Race Capitalism Justice that we were, in fact, in the beginning of a Second Nadir with the election of Donald Trump. Another historian, Sundiata Cha-Jua, proposed in the pages of Black Scholar that African Americans were already faced with a Second Nadir in 2010—at the midpoint of Barack Obama’s first term, but also during an era of weakening economic power for black people and continuing police violence against people of color. New York Times Magazine reporter Nikole Hannah-Jones, Atlantic writers Vann C. Newkirk and Ta-Nehisi Coates, and Slate reporter Jamelle Bouie have all warned in their works of the backslide of the tenuous gains made by African Americans during and after the civil rights movement. In the contest over power, justice, and freedom that has defined American history, things have often gotten worse before they got better.

Nonetheless, the Third Reconstruction idea holds some merit—if for no other reason than that both previous Reconstructions similarly rested on shaky progressive political coalitions doing ideological battle against incredible forces of reaction. Today, those organizing with the Democratic Socialists of America, the Poor People’s Campaign, teachers’ unions, and the Fight for $15 understand just how tightly intertwined their battles are. This new coalition will have to do battle by marching, through political education, and at the voting booth to achieve victory. The political climate today offers both peril and promise for the future—just as the previous two Reconstructions did.

Robert Greene is a PhD candidate in History at the University of South Carolina, who studies American intellectual history and Southern political history. He has been published in Dissent, In These Times, and Scalawag, and is the book review editor of the Society of U.S. Intellectual Historians.