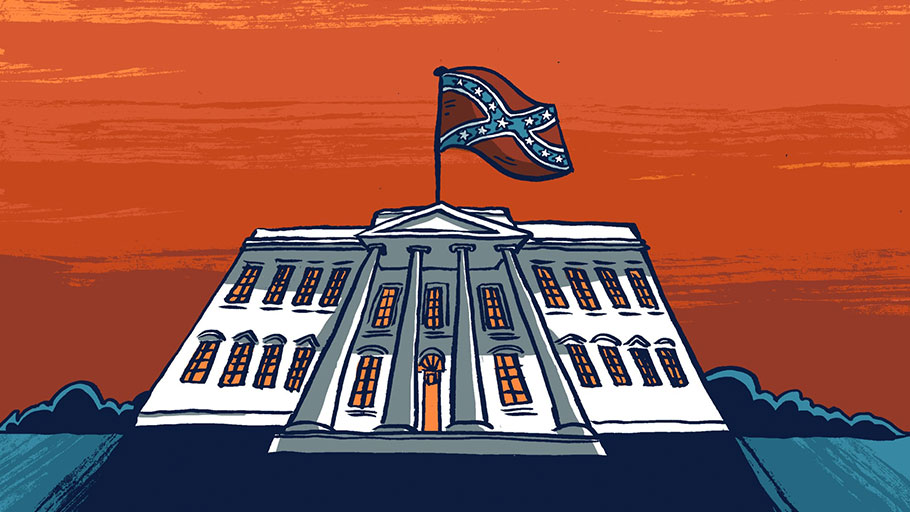

An image from the Capitol captures the distance between who we purport to be and who we have actually been.

By Clint Smith—

On Wednesday afternoon, as insurrectionists assaulted the Capitol, a man wearing a brown vest over a black sweatshirt walked through the halls of Congress with the Confederate battle flag hanging over his shoulder. One widely circulated photo, taken by Mike Theiler of Reuters, captured him mid-stride, part of the flag almost glowing with the light coming from the hallway to his left. Just above and behind him is a painting of Charles Sumner, the ardent abolitionist senator from Massachusetts.

On May 22, 1856, Sumner was attacked by Preston Brooks—a pro-slavery member of the House of Representatives from South Carolina—for a speech Sumner had made criticizing slaveholders, including Brooks’s cousin Andrew Butler, a senator representing South Carolina. Brooks attacked Sumner on the Senate floor. “Mr. Sumner, I have read your speech twice over carefully. It is a libel on South Carolina, and Mr. Butler, who is a relative of mine,” he said. Before Sumner could fully respond, Brooks began beating him over the head with the golden head of his thick walking cane, trapping Sumner under his desk as he tried to escape, until two representatives were finally able to intervene and bring him out of the chamber. Sumner did not return to the Senate for three years, and would experience ongoing, debilitating pain for the rest of his life.

Also behind the man in Wednesday’s photo, partially obscured by the rebel flag, is a portrait of John C. Calhoun. A senator from South Carolina and the vice president under both John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson, Calhoun wrote in 1837: “I hold that in the present state of civilization, where two races of different origin, and distinguished by color, and other physical differences, as well as intellectual, are brought together, the relation now existing in the slaveholding States between the two, is, instead of an evil, a good—a positive good.”

The fact that this photo was taken the day after voters in Georgia chose the first Black person and the first Jewish person in the history of that state to serve in the Senate; that it shows a man walking past the portrait of a vice president who urged the country to sustain human bondage and another portrait of a senator who was nearly beaten to death for standing up to the slavocracy; that it portrays a man walking with a Confederate flag while a mob of insurrectionists pushed past police, broke windows, vandalized offices, stole property, and strolled through the halls of Congress for hours, forcing senators and representatives into hiding and stopping the certification of the electoral process—it is almost difficult to believe that so much of our history, and our current moment, was reflected in a single photograph.

This photo seemed to capture the divide between who we purport to be and who we have actually been, the gap between our founding promises and our current reality.

The flag the man carried, which we have all come to associate with the Confederacy, was not the first that flew over the Confederate States of America.

In 1861, following the election of Abraham Lincoln, southern states began seceding from the Union in order to perpetuate the institution of human bondage. As Mississippi said during its secession convention, “Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery—the greatest material interest of the world.”

That year, a contest invited people to submit designs for the new Confederacy’s national flag. The winner was a design known as the “Stars and Bars,” which had three horizontal stripes—two red and one white in between—and a blue square with a ring of white stars in its top left-hand corner. Its resemblance to the American flag is clear, and perhaps unsurprising, given that many of the Confederacy’s military leaders had previously served in the U.S. Army. But in other ways, its likeness perhaps seems strange. The National Flag Committee of the Confederate States of America, in presenting the winning design, wrote: “A flag should be simple, readily made, and capable of being made up in bunting; it should be different from the flag of any other country, place or people; it should be significant; it should be readily distinguishable at a distance; the colors should be well contrasted and durable; and lastly, and not the least important point, it should be effective and handsome.”

The Stars and Bars was not, in fact, readily distinguishable from the American flag, which would prove problematic on the battlefield. On July 21, 1861, about 30 miles southwest of Washington, D.C., Confederate and Union soldiers met in the First Battle of Bull Run. The Confederacy prevailed, but not without tactical confusion and distress. Some Confederate soldiers wore blue uniforms instead of gray and some Union soldiers wore gray ones instead of blue. And when soldiers and officers on either side looked out over the field of smoke and blood and bodies, they could not easily tell the difference between the Stars and Bars and the Stars and Stripes.

After the battle, the Confederate general P. G. T. Beauregard appealed for a new flag so as to avoid such dangerous confusion, and in November of 1861, new Confederate battle flags began to appear. There were multiple iterations of the design, but the most common version included 13 stars (for the 11 states that seceded, plus Missouri and Kentucky) inside a blue diagonal cross trimmed with white, all against a red backdrop. In 1863, this design was placed in the top-right corner of a larger white flag to become the Confederacy’s first official national flag, known as the “Stainless Banner.” That version, however, was criticized because it looked too much like the bare white flag of surrender.

Over the course of the past century and a half, the design of the Confederate battle flag became inextricably linked to the story of the Confederacy. The flag’s symbolism cannot be disentangled from the cause of those who fought beneath it. It cannot be separated from the words of its vice president, Alexander Stephens, who wrote in his infamous Cornerstone Speech that slavery was “the immediate cause of the late rupture and present revolution” and that the Confederacy had been founded on “the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man.”

As I looked at the photograph on Wednesday, I thought of how the flag had expanded and evolved in meaning, how it had become a staple of Ku Klux Klan rallies, how it had been waved by white people attempting to intimidate Black children who were integrating schools after Brown v. Board of Education, how it had been made a part of flags in states whose legislatures worked tirelessly to disenfranchise Black citizens. And now it will forever be associated with the January 6, 2021, insurrection at the Capitol, when the nation watched a new iteration of white-supremacist violence, incited by a deranged and cowardly president.

During the Civil War, the Confederate Army never reached the Capitol. The rebel flag, to my knowledge, had never been flown inside the halls of Congress until Wednesday. Two days ago, a man walked through the halls of government bearing the flag of a group of people who had seceded from the United States and gone to war against it. Then, presumably, he walked out—carrying so much of this country’s history with him.

Source: The Atlantic