Black people in the United States inhabit a unique and precarious space in discussions of the horrible recent events in the Middle East.

By Karen Attiah, The Washington Post —

In the 1950s, the wave of decolonization was sweeping Africa and the Black civil rights struggle in the United States was picking up steam. According to historian Tyler Stovall, the battle for Algerian independence from France was a thorny issue for expat Black Americans. They saw themselves as refugees from America’s racism, yet they could be expelled by France for championing the Algerian cause.

Literary giants such as Richard Wright largely chose to protect their status as residents of France by remaining silent on the Algerian war and the oppression of immigrant Arabs, but writer William Gardner Smith did not. In his novel “The Stone Face,” the main character, Simeon, is a Black man who leaves the racism of the United States to live in Paris. Simeon encounters a French policeman brutalizing an Arab man, which triggers his memories of police encounters in America.

Since the Hamas attack on Israel on Oct. 7, and Israel’s subsequent assault on Gaza, I’ve been thinking about solidarities, allegiances and the unique yet precarious space that Black people in America fill in discussions of these horrible events within the context of Western colonization and liberation.

Many of us were horrified at the initial attack and hostage-taking by Hamas, while also feeling as though we are currently watching the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians in real time. Palestinian casualties skyrocket, while President Biden and Black members of his administration have said yes to more weapons and no to cease-fires.

I’ve had conversations with White, Jewish friends who are perplexed by, and resistant to, suggestions that the conflict between Israel and Palestinians has anything to do with race issues, or the dreaded “d” word: decolonization. A recent New York Times article talks about the abandonment that progressive Jews are feeling about being placed in the same category with whiteness. Their reactions are sometimes tinged with a suggestion that Black people are not educated enough on the history and politics of the conflict to understand the dynamics — and to speak about it.

None of these conversations are new to anyone who knows Black internationalist history. Black writers and civil rights leaders have a long history of seeing the Israeli-Palestinian conflict through the lens of the Black struggle for freedom and resistance to violent imperialism. Malcolm X criticized Zionism as colonialism. In 1974, Muhammad Ali traveled to a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon and declared support for the Palestinian cause. Huey P. Newton and the Black Panther Party also expressed support. Unfortunately, when it came to the Nation of Islam, antisemitism marred whatever valid critiques were leveled at Israel’s policies.

We know the West deeper than it knows itself. Today’s violence is a legacy of the British Empire’s strategy to “divide and rule,” by which a small island of European colonizers used strife as a weapon to enhance their power. Colonies where people fought among themselves could be ruled from a distance using relatively little force. In his piece “Open Letter to the Born Again,” published by the Nation in 1979, James Baldwin (who, as an expat, was outspoken about Arab rights in Algeria and in France, despite the risks) wrote about the colonial underpinnings of the Mideast crisis:

“The state of Israel was not created for the salvation of the Jews; it was created for the salvation of the Western interests. … The Palestinians have been paying for the British colonial policy of ‘divide and rule’ and for Europe’s guilty Christian conscience for more than thirty years.”

Given that many countries around the world were either colonized by the British or experienced U.S. military occupation in the post-World War II era, this conflict has come for many of us to symbolize “the West vs. the Rest.” And when it came to the Middle East, in particular, the work of Palestinian American scholar Edward Said, and his concept of orientalism helped connect the dots on how the United States’ support for Israel was reproducing Europe’s old colonial habits.

It should be no surprise that there are Black solidarities with the Palestinian plight. Many of us remember when, in 2014, Palestinians gave protesters of U.S. police brutality advice on how to deal with tear gas. After all, police in the United States were using the same tactics and equipment against protesters that the Israeli security forces were using. In 2020, Palestinians drew murals of George Floyd in solidarity with those in the West protesting police brutality.

We understand and lament that Black taxpayer money pays for gas and bullets used here and in Gaza. We see U.S. money going to war instead of our poor. We are expected to take pride in U.N. ambassador Linda Thomas-Greenfield, even though she vetoed a cease-fire motion at the United Nations, because, you know, representation.

Meanwhile, Black people can be discredited as antisemitic and punished simply for advocating justice for Palestinians. In 2018, Marc Lamont Hill was removed as a commentator from CNN after expressing solidarities with Palestinians. In Canada, just a few days ago, Sarah Jama, a member of Provincial Parliament for the Ontario New Democratic Party, was kicked out of the party for calling for a cease-fire and an end to the occupation of Palestinian land.

These are all difficult conversations to have — another legacy of the original divisions sown by colonial powers. Division is the whole point: Divided societies are more easily conquered by the authoritarian forces that care nothing for Jews, Blacks, Muslims or “other” identities. One day, we will have to move past the idea that over-funded military budgets, armed police forces, forced displacement of “the other” with impunity, and violence are the only means to peace and safety. We will arrive at basic respect and dignity of people.

We aren’t there yet. But I can have a dream.

Source: The Washington Post

Karen Attiah is a columnist for The Washington Post and writes a weekly newsletter. She writes on international affairs, culture and social issues. Previously, she reported from Curacao, Ghana and Nigeria.

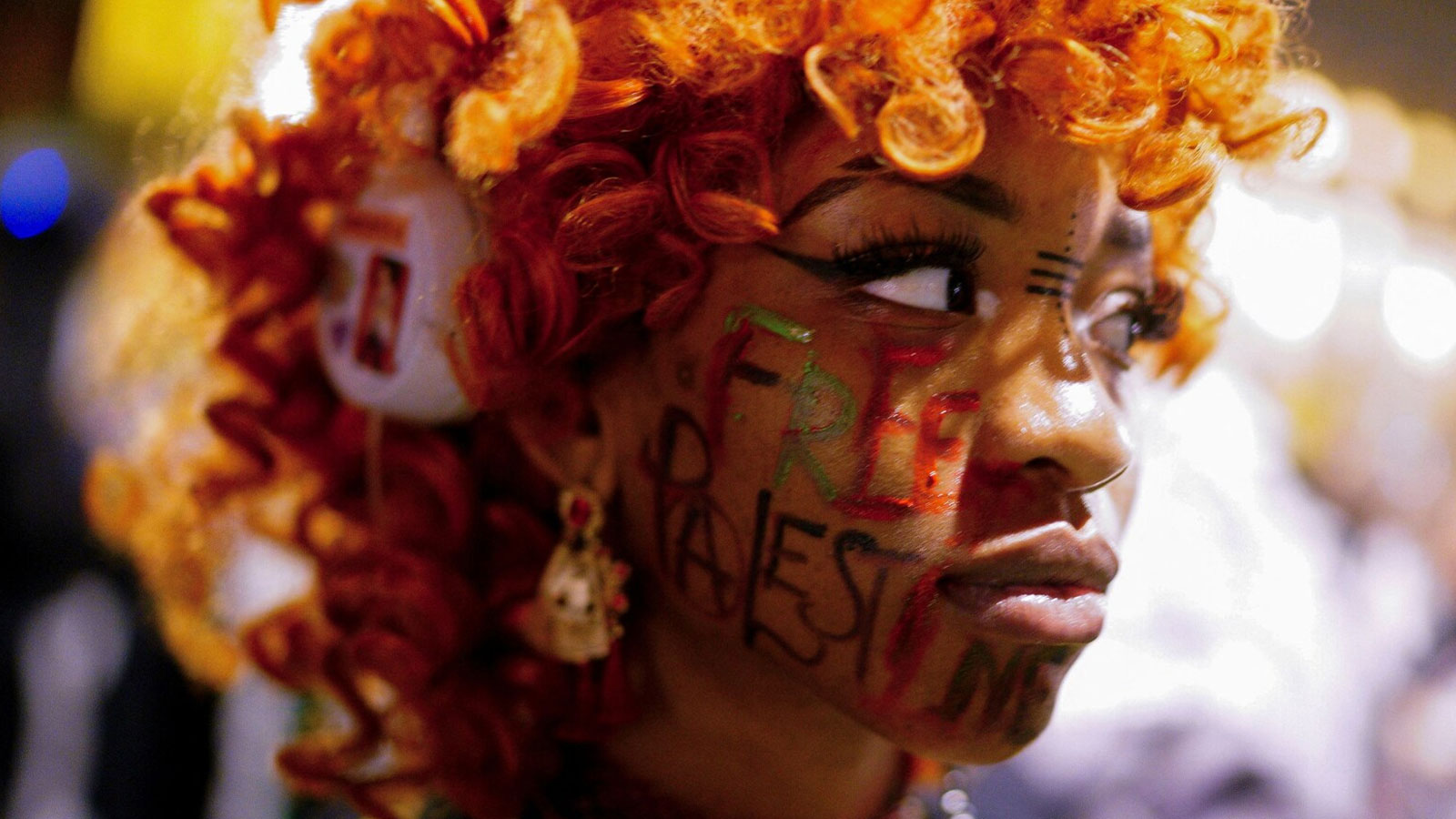

Featured image: A woman attends a demonstration in New York on Thursday to express solidarity with Palestinians in Gaza. (Eduardo Munoz/Reuters)