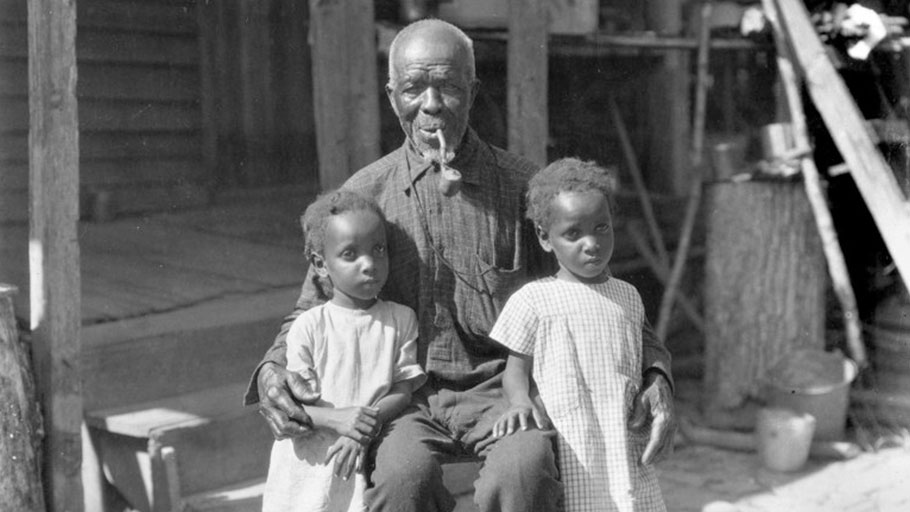

The literature on the African slave trade, Hurston wrote, had endless “words from the seller, but not one word from the sold.” Photo by Carl Van Vechten, Carl Van Vechten Trust, Beinecke Library, Yale

Hurston spent years turning an account of the transatlantic slave trade into a book. Then the manuscript languished for nearly nine decades.

Captain William Foster left Mobile in secret and returned the same way. On July 8, 1860, he dropped anchor in the waters off the coast of Mississippi, hid his cargo below deck, slipped ashore, and travelled overland to fetch a tugboat from Alabama. By then, Foster and his ship had survived a hurricane, a mutiny, an ambush, and a transatlantic journey, but late that Sunday night, after the tug carried him up the Mobile River to Twelve Mile Island, the Captain emptied his hold, dismissed his crew, and set fire to his ship. The Clotilda, Foster would forever after complain, was worth more than his share of what it had smuggled.

Although the international slave trade had been outlawed in America more than half a century earlier, Foster and three co-conspirators, a trio of brothers by the name of Meaher, had purchased a hundred and twenty-five men, women, and children, from Benin and Nigeria, to traffic them into the United States. The plan had been hatched a year before, when one of the Meahers got into an argument: a New Yorker insisted that slaves could no longer be transported across the Atlantic, a Louisiana planter wagered a hundred dollars that it could be done, and Timothy Meaher bet a thousand that he could be the one to do it.

The market for slaves had grown tremendously in the previous five decades. Absent imports, slavers relied on reproduction and relocation for their supply, and, as labor-intensive agriculture shifted to the Deep South, more than a million enslaved people were forced there by ship, rail, and sometimes by foot, in coffles. By the middle of the nineteenth century, domestic slave prices were so high that many planters had begun lobbying to reopen the global trade.

Among them were the Meahers, who had moved from Maine to Alabama, where they owned sawmills, steamboats, plantations, and people. To increase their holdings and win the bet, they recruited Foster, a Nova Scotian shipbuilder, and chose the Clotilda from among his ships. Although the schooner was fast enough to evade capture, it had to be refitted as a slave ship, with a false deck to conceal the necessary barrels of water, rice, beef, pork, sugar, flour, bread, molasses, and rum. Foster sailed from Mobile Bay with papers that claimed he was delivering lumber to St. Thomas, and eleven crew members who had not been told of their real mission. The nine thousand dollars in gold stashed on board to pay for the slaves played havoc with the ship’s compass, taking it off course; after that, a hurricane caught it just north of Bermuda. While repairing the ship, Foster’s men discovered the hidden deck, and threatened to alert the authorities.

Captain and crew negotiated a compromise, and reached Ouidah, on the west coast of Africa, a few weeks later. After eight days of discussion, Foster traded his rum and gold for more than a hundred slaves from the barracoons, as the holding pens were called. He loaded them onto his ship, and crossed the Atlantic in forty-five days. An estimated two million Africans died in the Middle Passage during the slave trade, but all the men and women on the Clotilda made it to Alabama alive. Neither the Meahers nor Foster were ever convicted of any crime, and, after five years of slavery, the survivors of the last transatlantic run were liberated by the Union Army. Free, but unable to raise the funds to return to Africa, many of them banded together to form Africatown, a settlement of their own just outside Mobile.

Kossola and his former shipmates worked in sawmills and powder mills, on farms and railroads, and as domestic help, until they had saved enough money to buy the land that became Africatown. Photograph from Erik Overbey Collection, Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of South Alabama

In the subsequent years and decades, the survivors of the Clotilda gradually died, until only one man answered the door in Africatown when a student from Barnard College came knocking, in 1927. The survivor’s name was Kossola; the student’s name was Zora Neale Hurston. Their first visit went badly, but Hurston wrote an article about Kossola’s life for the Journal of Negro Historyanyway. After that false start, she returned to Alabama several times to talk with Kossola, trying to learn, in her own words, “who you are and how you came to be a slave; and to what part of Africa do you belong, and how you fared as a slave, and how you have managed as a free man.”

Hurston spent four years turning what Kossola shared with her into a longer work of nonfiction, but no publisher wanted the resulting book—not then, not when the publication of “Jonah’s Gourd Vine,” in 1934, made her a celebrated novelist, and not even posthumously, after “Their Eyes Were Watching God” had sold more than a million copies. Hurston’s manuscript languished for nearly nine decades. Now HarperCollins has published “Barracoon: The Story of the Last ‘Black Cargo.’ ” Why it was rejected in Hurston’s lifetime, and how the residents of Africatown faded from her history and our own, is a story almost as plaintive as the one the book itself records.

Zora Neale Hurston and Langston Hughes were undergraduates when they ran into each other on the streets of Mobile, in the summer of 1927. Hurston was thirty-six, but still a semester shy of becoming the first black graduate of Barnard College; she was down below the Mason-Dixon Line to collect folklore and oral histories for the American Folklore Society and for the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History. She had been sent to tour Fort Mose, a black settlement founded by runaway slaves in Florida, and to talk with Kossola, but hadn’t got enough material “to make a flea a waltzing jacket.” Hughes was twenty-five and between semesters at Lincoln University, in Pennsylvania; he had gone South to read his poetry at Fisk University and at the Tuskegee Institute. Although Hughes and Hurston had crossed paths a few times in New York, they met in Alabama entirely by chance: when he got off the train at the M. & O. Railroad Terminal, Hurston happened to be walking down the street.

They went to lunch, then Hurston offered Hughes a ride home. Driving a Nash that she called Sassy Susie and carrying a chrome-plated pistol in her suitcase, Hurston was formidable even in her failures. She’d made a disastrous marriage two months earlier. Now, with her scanty research, she was courting the wrath of the professor who had arranged her travels: the renowned anthropologist Franz Boas. It was her “Barnardese,” Hurston said, that was alienating would-be subjects like Kossola. Hurston was born in the tiny Alabama town of Notasulga, and brought up in the all-black Florida town of Eatonville, which, like Africatown, was founded by former slaves in the years after the Civil War. But she no longer sounded like the daughter of a sharecropper turned Baptist preacher, much less like someone who had once earned her living as a waitress, a manicurist, and a maid. Her airs, she feared, were not only put-on but off-putting. Still, never one to acquiesce to circumstances, she cadged what she could from the records of the Mobile Historical Society to embellish what little Kossola had told her, and headed north with Hughes.

The two writers took the long way home, stopping to talk with conjurers, tramps, convicts, and backwoods preachers all over the South. Harlem Romantics, their Lake District was Dixie, and their lyrical ballads were the songs, stories, and tales they gathered—Hurston compiling transcripts for her academic work, Hughes jotting down phrases in his notebook. He didn’t have a license, so Hurston drove: from Mobile to Montgomery, from there to Tuskegee to meet with students, and then to Georgia, where they encountered Bessie Smith in Macon and toured the plantation where Jean Toomer gathered his material for “Cane.” They stopped on the way to South Carolina to meet with a root doctor, got a flat tire in Columbia, and then scooted up the coast. By September, they had returned to New York, where Hurston settled down to write her article on Kossola, who was then known mainly by his American name, Cudjo Lewis.

Most of what Hurston published in “Cudjo’s Own Story of the Last African Slaver” was cribbed from other people who had interviewed him; by one biographer’s count, forty-nine of the essay’s sixty-seven paragraphs were plagiarized, the bulk of them from Emma Langdon Roche’s “Historic Sketches of the Old South.” Not many noticed the transgression, least of all the wealthy white widow Charlotte Osgood Mason, a financial backer of Hughes, Alain Locke, and other Harlem Renaissance artists, who decided to offer Hurston a camera, a car, and two hundred dollars a month to collect more oral histories and folk stories down South.

Papa Franz, as Hurston called her supervisor, and Godmother, as she would come to call her patron, were impressed by how much she learned on her subsequent trips to Africatown. With each visit, she became less hurried, and Kossola grew more forthcoming. She brought him gifts—Georgia peaches, a Virginia ham, Bee Brand insect powder to ward off mosquitoes—and he allowed her to take pictures of him in his family cemetery and to make a short film of him chopping firewood. With Mason paying her salary, Hurston could take her time, coming and going as Kossola wanted, meeting his grandchildren, visiting his family’s graves, going with him to the church where he was sexton, and, in between, honoring the days he did not want to speak of his life in slavery, or of anything else.

When Hurston finally started writing, she dedicated “Barracoon” not to its subject but to Mason, and acknowledged in its preface what her earlier article had buried in a footnote—namely, her debt “to the records of the Mobile Historical Society.” In the introduction, she sketched the history of the Clotilda and the geography and the economics of the brutal trade that had ripped Kossola from his home. “Of all the millions transported from Africa to the Americas only one man is left,” she wrote—a man whose voice was crucial because the burgeoning body of literature on the African slave trade contained endless “words from the seller, but not one word from the sold.”

Hurston framed Kossola’s testimony as the last opportunity to reduce that deficit, and the twelve chapters that follow her introduction consist almost entirely of his words. She renders Kossola’s story as he told it, not only linguistically, in his dialect, but narratively, in his own wandering way—sending readers into sad silences and on distracted errands of the sort she’d shared with him, closing the garden gate on them the way he’d closed it on her. “Barracoon” does not so much shape Kossola’s story as transcribe it.

Kossola was only nineteen when the Army of Dahomey raided his inland village of Bantè, beheading his king and countless others, and kidnapping for the slave trade anyone who wasn’t elderly or injured. “I see de people gittee kill so fast! De old ones dey try run ’way from de house but dey dead by de door, and de women soldiers got dey head,” he told Hurston, before recalling the way the heads of his neighbors came to smell days after their decapitation. That stench followed him all the way to Abomey, where the palace was decorated with skulls and guards carried pikes topped with bleached bones. It was at Abomey that Kossola and the other prisoners were allowed to rest before being marched another sixty miles to Ouidah.

One of the great virtues of Hurston’s book is that it returns the wound of slavery, even in her time considerably calloused over on this country’s consciousness, to its raw and bloody state. Kossola could recall with great specificity the actions of Captain Foster, who tore him away from the African continent and made him into an American slave: “De white man lookee and lookee. He lookee hard at de skin and de feet and de legs and in de mouth. Den he choose.” Kossola recalled the horror of separation, first from his tribal family in Bantè, then from his companions in the barracoon. “Den we cry,” he said, “we sad ’cause we doan want to leave the rest of our people in de barracoon. We all lonesome for our home. We doan know whut goin’ become of us.”

Foster’s prisoners were loaded onto the Clotilda, shaved, stripped naked, and locked in darkness below deck for twelve days. On the thirteenth day, they were allowed into the light, and men and women who had never before seen the ocean could suddenly see nothing else. “I so skeered on de sea,” Kossola recalled. “De water it makee so much noise! It growl lak de thousand beastes in de bush.” Whenever other ships approached, the captives were hustled back into the hold, hidden from the American, British, Portuguese, and Spanish patrols enforcing the prohibitions on the slave trade.

In Alabama, the Africans were unloaded and spirited off to another boat for the trip to a plantation upriver. Captain Foster refused to pay his crew the double wages he had promised them under the threat of mutiny, and the seamen were hurried North to prevent them from revealing the slaves’ whereabouts to the authorities. But the Africans were already the talk of Mobile, and a few days after their arrival they had to be moved again so that federal officials could not seize them. Once the proverbial and actual coasts were clear, the Africans were divided among the men who had planned the transatlantic run.

“Cap’n Jim he took me,” Kossola said of James Meaher, who started calling the teen-ager Cudjo, and put him to work on a steamship, chopping wood to fuel its trips from Mobile to Montgomery. He labored that way, gruellingly and without pay, for five years and six months. Finally, on April 12, 1865, Union soldiers picking mulberries along the shoreline saw Kossola and the other slaves on Meaher’s steamboat and hollered a message at them: “You free, you doan b’long to nobody no mo’.”

Sixty-two years later, when Hurston met Kossola, many other men and women liberated by the war were still alive. Not long after she recorded Kossola’s story, she and other writers with the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Writers’ Project dispersed around the South, compiling the stories that would fill the seventeen volumes of “Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States.” Almost all of those stories progressed from captivity to emancipation, but Kossola’s account both began and ended in freedom: even in the final years of his life, he considered himself more African than American, and he could remember clearly an earlier, unquestioned liberty in his homeland.

He could not, however, return to it. Emancipation freed slaves only from bondage, not from destitution; the Clotilda survivors had no way of paying for their passage home. When they resolved, instead, to build a village of their own, it was Kossola who was tasked with asking one of their old slavers to provide the land for it, and he made a passionate speech to Timothy Meaher calling for reparations. When Meaher refused, Kossola and his former shipmates went back to work in sawmills and powder mills, on farms and railroads, and as domestic help, until they had saved enough money to buy the land that became Africatown.

Kossola moved there and married another survivor, a woman named Abile. They had six children, all of whom died in one tragedy after another—illnesses, a train accident, an unexplained disappearance, a police shooting. By the time Hurston arrived, Kossola had outlived his wife and children by almost two decades and was only a few years away from his own death. He was, Hurston wrote, “the only man on earth who has in his heart the memory of his African home; the horrors of a slave raid; the barracoon; the Lenten tones of slavery; and who has sixty-seven years of freedom in a foreign land.”

“Only” and “last” are siren songs for writers, alluring but dangerous. Meaning does not always, or even often, consolidate in sole survivors—and certainly it is not absent from those who perish—yet the temptation to imbue temporal accidents with surplus significance skews many accounts of history. Kossola did not necessarily possess greater knowledge or insight or wisdom about slavery or the slave trade than those who died before him, but Hurston was drawn to him because he was known near and far as the last living survivor of the Clotilda.

By the time Hurston arrived, Kossola had outlived his wife and children by almost two decades and was only a few years away from his own death. Photograph from Erik Overbey Collection, Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of South Alabama

As it turns out, though, even that wasn’t true, and Hurston knew it. Almost a year after her adventures with Hughes in Sassy Susie, she wrote a letter to him from Alabama. “Oh!” she exclaimed toward the end, “almost forgot”: she had found another survivor of the Clotilda living on the Tombigbee River, two hundred miles north of Africatown. The woman was older than Kossola, and, according to Hurston, a better storyteller. But there can’t be two lasts or more than one only, so Hurston, perhaps believing that Kossola’s story would be more valuable if people thought it was unique, told Hughes that she planned to keep this other survivor secret: “No one will ever know about her but us.”

Tragically, that proved true. Abandoning her training by Boas, and ignoring the dictates of both honesty and history, Hurston forsook the opportunity to record the story of another survivor. Later scholars have determined that the person Hurston “almost forgot” was most likely a woman named Allie Beren, but no film footage records her face, no known photographs document her home, no oral histories capture her memories. Instead of gathering any of that, Hurston returned to New York, and spent years shaping the transcripts of her many talks with Kossola into a book. When she finally finished, no publisher wanted it. Two houses rejected it outright, while another was interested only if Hurston was willing to render Kossola’s story “in language rather than dialect,” which she was not.

It is true that the long vernacular passages sometimes make “Barracoon” difficult to read. Yet, in retrospect, it seems probable that the book was rejected as much for the voice that isn’t in it as for the one that is. Contemporary readers who pick up “Barracoon” because it was written by Zora Neale Hurston will fail to find much of her in it. As flashy as fireworks in her own lifetime and bright as neon in ours, Hurston is barely visible in “Barracoon”; aesthetically as well as intellectually, she absents herself almost entirely from its pages. That’s admirable for an anthropologist, but grievous for a stylist as talented as Hurston. The novelist who would later summon a hurricane in her fiction and suspend readers above her naked body on the altar of a hoodoo priest in her nonfiction resigned herself to the role of scribe in “Barracoon.” Like Hurston herself, in those years, the book stalled out somewhere between academia and art.

Characteristically impervious to failure, Hurston responded to the rejection of her manuscript by going to work on “Jonah’s Gourd Vine.” With its publication, the very thing that had troubled at least one publisher about “Barracoon” became one of the most celebrated features of Hurston’s fiction: her ear for black vernacular speech. Affirmed by her success, she became a more confident writer, and began giving her own voice as much expression as the voices of her subjects. When editors clamored for more, she raided her cabinets and turned her earlier field work into a book called “Mules and Men,” which returns to the storytellers and singers of her childhood. A second collection of folklore, “Tell My Horse,” goes gonzo into the spiritual beliefs and practices of Haiti and Jamaica. Those books have more “I”s on single pages than entire chapters of the book she wrote about Kossola. Where “Barracoon” suffers from the lack of a guide, it is clear, in these narratives, that Hurston’s voice could lead the Minotaur off Crete.

What is not clear is why Hurston never returned to her earliest anthropological subject. Although she was obviously comfortable repurposing older work, she never rewrote Kossola’s story, or tried again to publish it as a stand-alone book. In the handful of pages devoted to Africatown in her autobiography, “Dust Tracks on a Road,” Hurston explains how her time with Kossola had “impressed upon me the universal nature of greed.” She knew before going South that Captain Foster had purchased the Africans, but learned from Kossola that the King of Dahomey had sold them: “My own people had butchered and killed, exterminated whole nations and torn families apart, for a profit before the strangers got their chance at a cut.” It’s impossible to know if she abandoned “Barracoon” because of that uncomfortable fact, because of her own academic misdeeds, because of her failure to record the testimony of another survivor, or for some other reason or for none at all. The manuscript went into Hurston’s archives and, for the better part of a century, stayed there.

“Lost” is as alluring an idea as “last,” but what happened to “Barracoon” is more complicated than mere disappearance. The manuscript was never missing. It is mentioned by all of Hurston’s biographers, including Robert Hemenway, Valerie Boyd, and Deborah G. Plant (who wrote and edited the introduction to this new publication), and Hurston’s time in Africatown was detailed more than a decade ago in Sylviane A. Diouf’s excellent and haunting book “Dreams of Africa in Alabama.” Yet the astonishing historical confluence of one of the last African slaves in America and one of the great American writers was somehow shrugged off by posterity. When the story of Africatown is told, Hurston is not always a part of it; when her anthropological work is read, Kossola is often left out of it. Many people have watched Hurston’s footage of him without knowing that she was the one behind the camera, an experience akin to reading the work of the German philosopher Ludwig Feuerbach and only later learning that it was translated by George Eliot.

Still, if “Barracoon” was never actually lost, Hurston was. By the fifties, her writing had fallen out of favor, and when the sales stopped so did the fellowships, grants, and stipends that had supported her early work. Meanwhile, her politics, like her circumstances, grew dire—she opposed everything from the New Deal to the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education—until she was estranged from the black intellectual circles that had once embraced her. She left New York after being falsely accused of molesting the son of a landlord in 1948; the trial attracted more attention than her acquittal, and those lurid headlines were among the last that she made in her lifetime. She went home to Florida, where she once again found work as a maid, while laboring tirelessly on a quixotic biography of King Herod. She died in 1960, in a county welfare home. During that time, Africatown suffered a similar decline—its founders long deceased, their descendants struggling to preserve the settlement as paper mills and oil-storage tanks staged a toxic encroachment on its borders.

What rescued Hurston from obscurity was an act of pilgrimage not unlike the one that she had made to Kossola three decades earlier. In 1973, Alice Walker went looking for Hurston’s unmarked grave. When she found it, she paid for a tombstone; more important, for generations of readers, she brought Hurston back to life. Walker offered no apologies for Hurston’s dishonesty and disastrous acts of self-sabotage, but in an article that appeared in Ms., “In Search of Zora Neale Hurston,” she made the case for Hurston’s place in the canon.

Thanks to Walker, we now have multiple editions of Hurston’s novels, autobiography, and other nonfiction, including “Every Tongue Got to Confess,” a posthumous collection compiled from her field notes. But “Barracoon” arrives decades late, Hurston’s very first work transformed into her very last—a coda to her career, yet vital to our ongoing conversation about race and reparations. Walker has written a foreword, in which she speculates that resistance to the book over time has stemmed from what Hurston herself found shocking: Kossola’s frank account of “the atrocities African peoples inflicted on each other, long before shackled Africans, traumatized, ill, disoriented, starved, arrived on ships as ‘black cargo’ in the hellish West.” One of the virtues of “Barracoon,” then, is that it may help teach us to live with uncomfortable truths, not only about the complicated and terrible story it records but also about the complicated and tremendous author who recorded it.

This article appears in the print edition of the May 14, 2018, issue of The New Yorker, with the headline “Survivor Bias.”

Casey N. Cep is a writer from the Eastern Shore of Maryland. Her first book, “Furious Hours: Harper Lee and an Unfinished Story of Race, Religion, and Murder in the Deep South,” is forthcoming.